Iran prefers operating on the margins, not in the spotlight. Its strategic culture thrives on ambiguity and deniability. Tehran uses proxies, sabotage, cyber tools, and covert action to advance regional ambitions without full-scale war or direct attribution. From Beirut to Berlin, Iran’s irregular warfare network lets it punch above its weight. The regime shapes outcomes through calculated escalation and plausible deniability. These tools help Iran influence conflicts, deter rivals, and project power beyond conventional military capabilities.

This approach is not borne of desperation—it is deliberate, shaped by ideology, doctrine, and decades of refinement. Rooted in the legacy of the 1979 Islamic Revolution, it is embedded in institutional structures and national narratives. Iran’s irregular strategy reflects a belief that sustained, deniable asymmetric pressure is more effective than open confrontation. This article maps the architecture, tactics, and implications of Iran’s shadow strategy across regions and domains.

Revolutionary Doctrine Meets Asymmetric Strategy

The 1979 Islamic Revolution was itself an irregular campaign—a decentralized, populist uprising that fused religious zeal, political grievance, and revolutionary organization. Iran institutionalized that model almost immediately. The new regime’s constitution formalized the export of revolution in Article 150, mandating that elements of the armed forces “carry out jihad for the sake of God… and extend the sovereignty of God’s law throughout the world.” This was not a rhetorical flourish—it became a guiding principle of statecraft. The result is a hybrid model that combines ideology, doctrine, and pragmatism, enabling Tehran to conduct influence campaigns and proxy conflicts in parallel with diplomatic efforts.

The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) was created to defend the state and protect the revolution, both domestically and internationally. It was designed to supplant the regular military and serve as Iran’s ideological shield. Today, the IRGC controls a sprawling, covert global network. Its influence extends into intelligence, economic ventures, cyber capabilities, and irregular warfare. From the Quds Force abroad to the Basij militia at home, the IRGC drives Iran’s asymmetric strategy.

The IRGC-Quds Force: Global Covert Power

Central to Iran’s strategy is the Quds Force, a semi-autonomous arm of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC). It operates under the direct authority of Iran’s Supreme Leader. The Quds Force acts as both a covert military unit and a foreign policy tool. It bridges kinetic operations with ideological influence. Unlike conventional forces, it specializes in non-linear conflict. Its battlefield is regional instability, and its weapon is persistent ambiguity.

Its core mission set includes recruiting, training, and financing proxy forces across the Middle East and beyond, often embedding advisors directly within militia command structures. It plans and enables sabotage operations, targeted assassinations, kidnappings, and cyber intrusions abroad—typically without fingerprints. It maintains logistical and financial supply chains through a sophisticated web of smugglers, front companies, informal money systems like hawala, and diplomatic cover.

Equally important is its orchestration of influence operations—supporting media fronts, religious outreach, and soft-power political interference through NGOs or hidden proxies. With regional operatives embedded in embassies, religious seminaries, and diaspora communities, the Quds Force sustains global reach while preserving operational deniability and strategic flexibility.

The “Axis of Resistance”: An Integrated Proxy Network

Iran’s reliance on proxy groups is not circumstantial—it’s foundational. Its extended network, known as the “Axis of Resistance,” includes:

Hezbollah (Lebanon)

Hezbollah is Iran’s crown-jewel proxy and the template for every other partner force. Established during the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon, it has evolved into a hybrid organization with political, military, and social-welfare arms that collectively overshadow the Lebanese state. Operationally, Hezbollah fields an expeditionary force of 45,000–55,000 fighters—including a 20,000-strong standing cadre—equipped with antitank guided missiles, UAVs, and an estimated 150,000 rockets and precision-guided munitions aimed at Israel. The group’s elite Radwan Unit rehearses cross-border raids while its naval unit trains with C802 and Noor anti-ship missiles capable of contesting the Eastern Mediterranean.

Politically, Hezbollah holds decisive blocs in parliament and key ministries, funneling state resources into its “Jihad al-Binaa” construction arm and extensive social-service network, thus buying enduring legitimacy among Lebanon’s Shia population. Financially, it blends Iranian funding—estimated at $700 million annually—with global fundraising, licit businesses, and narco-trafficking revenues. During the Syrian Civil War, Hezbollah rotated up to 10,000 fighters through Aleppo, Qalamoun, and Daraa under IRGC direction, gaining urban-combat experience and testing new drone and EW systems. Its integration into Lebanese society, combined with expeditionary reach and a deep arsenal, makes Hezbollah both Iran’s premier deterrent against Israel and a forward operating base for regional power projection.

Iraqi Shia Militias

Iraq hosts a constellation of Shia militias that act as Iran’s strategic depth west of the Zagros. The core groups—Kata’ib Hezbollah (KH), Asa’ib Ahl al-Haqq (AAH), Harakat al-Nujaba, and parts of the Badr Organization—sit inside the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF), a nominally state-controlled umbrella created in 2014 to fight ISIS but now institutionalized within Iraq’s security architecture. These factions answer first to IRGC-Quds Force liaisons, not Baghdad, enabling Tehran to harass U.S. installations with rockets, one-way drones, and explosively formed penetrators while maintaining plausible Iraqi sovereignty.

KH and AAH possess precision short-range ballistic missiles and kamikaze UAVs—often assembled from Iranian kits at covert workshops near Jurf al-Sakhar and Basra. Politically, militia-aligned parties leverage bloc votes in parliament to shape ministries, budget allocations, and oil contracts, ensuring a revenue stream that supplements direct Iranian cash. Many commanders, including KH’s Abu Hussein al-Hamidawi, served with the IRGC during the Syrian war, creating a cross-theater cadre fluent in proxy warfare. As U.S. troop levels shrink, these militias increasingly police the Iraq-Syria border, move Iranian weapons to Hezbollah, and intimidate reformist activists—cementing Iran’s influence from Diyala to Deir ez-Zor without deploying uniformed forces.

Fatemiyoun and Zaynabiyoun Brigades

The Fatemiyoun Division and Zaynabiyoun Brigade represent Iran’s expeditionary legions drawn from Afghan and Pakistani Shia communities. Recruitment exploits socioeconomic vulnerability: Afghan Hazaras in Iran’s construction sector and Pakistani Shia in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa are offered residency permits, monthly stipends (~$600), and martyr pensions for families. Trained at IRGC camps in Yazd and Qom, fighters receive instruction in infantry tactics, IEDs, and drone spotting before rotating to Syria, where they have fought in Aleppo, Palmyra, and the southern front near Daraa. At their peak (2017–2018), the units fielded 15,000–20,000 combatants; today, an estimated 8,000 remain on call, garrisoned around Damascus and Deir ez-Zor.

Iran issues “Shrine Defender” narratives, framing deployments as a sacred duty to protect Sayyidah Zaynab’s mausoleum, bolstering ideological cohesion. Command and control flow through Quds Force safehouses. Afghan and Pakistani mid-level officers are vetted for loyalty and rotated into IRGC staff colleges, creating a future cadre of Tehran-aligned veterans across Central and South Asia. Beyond Syria, select graduates have been identified training Houthi and PMF recruits in sniper tactics and UAV assembly. This indicates Tehran’s intent to leverage this multinational pool as a modular force wherever Iranian interests require boots—not necessarily Iranian—on the ground.

Houthis (Yemen)

Ansar Allah—commonly called the Houthis—evolved from a local Zaydi revivalist movement in Yemen’s Saada province into Iran’s southwestern lever against Riyadh and maritime commerce. Since 2014, the Quds Force and Lebanese Hezbollah advisers have transformed the group from tribal insurgents into a technologically sophisticated actor wielding ballistic missiles (Badr-1P, Burkan-2H), Qasef-2K loitering munitions, and Samad-series UAVs with ranges exceeding 1,000 km. Smuggling pipelines run through Oman’s Mahra governorate and Eritrean ports, funneling Iranian guidance kits, UAV engines, and anti-ship missiles hidden in aid shipments or shows.

Operationally, Houthi forces have targeted Saudi oil infrastructure (Abqaiq-Khurais, 2019), Abu Dhabi’s Mussafah fuel depot (2022), and Red Sea shipping, forcing insurers to hike premiums and compelling the U.S. Navy to station a drone-hunter task force in the Bab el-Mandeb. Politically, the movement administers northern Yemen, levying taxes on Hodeidah port traffic and maintaining a parallel central bank, reducing dependency on Tehran even as Iranian technical support deepens. Ideologically, “Death to America, Death to Israel” slogans echo Iranian revolutionary rhetoric, reinforcing alignment. The Houthis thus serve Tehran as both a battering ram against Saudi Arabia and a strategic wrench in one of the world’s busiest maritime chokepoints.

Smaller Militia Cells

Beyond headline proxies, Iran cultivates a lattice of smaller militant cells designed for deniable flashpoint activation. In Bahrain, Saraya al-Ashtar and Saraya al-Mukhtar conduct periodic IED attacks against police, financed and trained through IRGC facilitators in Mashhad and Basra. In Gaza, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) receives Iranian rockets, funds, and technical advisers independent of Hamas’s political calculations, allowing Tehran to spark conflicts with Israel at times of its choosing. Syrian offshoots such as Liwa al-Quds and the Imam al-Hussein Brigade secure Aleppo industrial zones and the Abu Kamal corridor, safeguarding the so-called “land bridge” from Tehran to the Mediterranean.

In Saudi Arabia’s Eastern Province, covert arms caches discovered in 2020 traced back to Quds Force maritime drops, hinting at sleeper-cell infrastructure among Shia communities. Elsewhere, West African Shiite movements—like Nigeria’s Islamic Movement under Ibrahim Zakzaky—receive ideological material and occasional funding, offering Tehran future leverage on Atlantic littorals. These micro-proxies typically field a few dozen to a few hundred operatives, rely on encrypted messaging apps, and stockpile small arms, explosively formed projectiles, or commercial drones. Their strategic value lies not in battlefield mass but in Tehran’s ability to threaten multiple fronts simultaneously, stretching adversary intelligence and security resources thin.

Cyber and Influence Operations: The Digital Battleground

Iran’s investment in cyberwarfare and information operations has grown in soIran’s investment in cyberwarfare and information operations has grown in both scale and sophistication over the past decade, positioning Tehran as a credible digital threat actor alongside Russia and China. Its cyber strategy, directed in large part by the IRGC and the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), emphasizes asymmetric disruption, deniability, and psychological impact.

Groups such as APT33, APT34, and other IRGC-linked hacking teams conduct offensive cyber operations targeting U.S. financial institutions, Israeli critical infrastructure, European utilities, and Gulf ministries. These intrusions range from credential harvesting and network infiltration to ransomware deployment and operational sabotage. Notable incidents include a 2024 breach of a water-treatment facility near Tel Aviv and a wave of energy-sector ransomware attacks in Germany, reportedly timed with diplomatic pressure on Tehran.

Domestic

Domestically, Iran maintains a sprawling surveillance ecosystem. The state leverages facial recognition software, mobile metadata tracking, and informant networks embedded in universities and workplaces to monitor dissent. These capabilities were intensified following the 2022 Mahsa Amini protests, where digital footprints were used to preempt and suppress demonstrations.

Global

Globally, Tehran runs influence operations using troll factories, fake news sites, and online personas. These assets amplify sectarian narratives, anti-Western sentiment, and regime-friendly messaging. Campaigns often exploit tensions within diaspora communities, stirring division and mistrust. Documented overlaps exist between Iranian and Russian disinformation teams, especially during the 2022 European elections. These collaborations suggest shared infrastructure and strategic alignment between authoritarian actors.

A 2023 Mandiant Intelligence report documented a 43% rise in Iranian cyberattacks on European critical infrastructure. The surge followed Gaza war flare-ups, showing Tehran’s readiness to escalate during regional crises. Cyberspace serves as both a battlefield and a pressure valve. Iran’s digital playbook treats online disruption as a tool for strategic signaling, coercion, and denial—all within its irregular warfare doctrine.

Internal Repression: The Domestic Paramilitary State

Iran’s shadow warfare isn’t solely external—it is deeply embedded within the structure of its domestic governance. The Basij, a volunteer paramilitary branch of the IRGC, serves as the regime’s grassroots enforcer and a key pillar of internal control. With an estimated membership exceeding one million, the Basij operates across every province, university, and major employer in the country.

Functionally, the Basij performs crowd control and riot suppression, as seen during the 2022–2023 Mahsa Amini protests, when they were deployed alongside police and IRGC forces to violently disperse demonstrators. Their role extends beyond the enforcement of morality codes; they act as first responders to dissent, often with brutal efficiency.

The Basij also functions as an informal intelligence apparatus, maintaining a pervasive presence in schools, religious centers, and workplaces. Members collect personal data, report political deviance, and intimidate civil society actors, feeding information directly to the Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS).

During wartime or periods of regime insecurity, the Basij serves as a mass mobilization engine, trained in irregular warfare, indoctrination, and rear-area security. The MOIS complements this structure by extending coercion beyond Iran’s borders. A 2022 German intelligence report confirmed that MOIS operatives had plotted multiple assassinations of Iranian dissidents in Berlin and Düsseldorf, illustrating the regime’s willingness to project repression transnationally.

Unconventional Weapons

Iran employs a range of unconventional weapons to create asymmetric effects across multiple domains. These include sea mines and submersible drone boats deployed in the Strait of Hormuz and the Bab el-Mandeb, threatening global shipping routes critical to energy markets. Additionally, Iran has demonstrated its capacity to launch precision drone-based missile attacks on targets hundreds of kilometers away, such as the Abqaiq and Khurais oil facilities in Saudi Arabia in 2019, and Abu Dhabi’s airport infrastructure in 2022. These systems, often low-cost and hard to intercept, allow Iran to project force while remaining below the threshold of overt war.

Sabotage Campaigns

Iran uses sabotage as a strategic signaling tool—applying pressure while avoiding attribution. Suspected operations include the 2021 attack on Israel’s Karish offshore gas rig, repeated damage to Saudi Aramco pipelines, and fires at Gulf petrochemical plants and port infrastructure. These actions disrupt energy markets and heighten regional tensions without requiring direct military confrontation. Sabotage teams often operate through intermediaries, relying on trained proxies, cyber triggers, or embedded operatives. By targeting economic chokepoints, Iran leverages sabotage not merely for destruction, but for political messaging—demonstrating reach, resilience, and the ability to punish adversaries without conventional escalation.

Assassination and Kidnap Operations

Iran has a long track record of using assassination and abduction to eliminate dissidents, intimidate defectors, and deter opposition abroad. The Ministry of Intelligence and Security (MOIS), often working in coordination with Quds Force operatives, has conducted or attempted such operations in countries including Germany, Turkey, Iraq, the UAE, and the United States. Targets typically include exiled journalists, former military officials, and regime critics in the diaspora. Methods vary—from poison and vehicle bombs to kidnapping attempts disguised as extraditions. These operations serve both domestic and foreign objectives: silencing threats while warning others of the regime’s global reach.

Denial and Dual-Use Logistics

Iran’s irregular operations are sustained by a deeply embedded logistics architecture designed for maximum deniability. Front companies registered in Asia, Africa, and Latin America handle the procurement of sanctioned components. Charitable organizations and religious institutions serve as financial conduits. IRGC couriers exploit diplomatic pouches and state-linked airline cargo holds to move cash, weapons parts, or encrypted communications. Dual-use goods—such as electronics or chemical precursors—are routed through legitimate trade channels, masked by falsified manifests and layered ownership structures. This blend of licit and illicit networks makes attribution difficult and interdiction costly, enabling Iran to conduct strategic operations under the radar.

Global Penetration: Beyond the Middle East

Iran is adaptable and global. Its irregular warfare architecture extends beyond the Middle East into peripheral theaters where oversight is weak, state capacity is low, or political alignment is favorable.

In Latin America, Tehran maintains historic alliances with Venezuela’s Maduro regime and Hezbollah-linked financial networks in Brazil, Paraguay, and Colombia. These networks launder money through car dealerships, import-export businesses, and informal banking hubs in the Tri-Border Area. IRGC operatives have also provided countersurveillance training and technical help to sympathetic regimes. They build influence under the guise of anti-imperialist solidarity.

In Africa, Iranian “cultural centers” and quasi-religious missions in Nigeria, Senegal, and Tanzania offer safe routes for Quds Force and MOIS operatives. These hubs are used to recruit local assets, move small arms, and host ideological events. Their activities support Tehran’s transnational Shia identity campaign and expand regional influence.

In Europe and North America, Iranian operatives embedded within diaspora communities engage in dual-use technology procurement, surveillance of dissidents, and targeting of soft infrastructure. MOIS plots uncovered in Germany, France, and Canada have highlighted the scope of this effort.

In Southeast Asia, Iran quietly gathers intelligence on Israeli, U.S., and Gulf-affiliated targets—using embassies, shell companies, and students as covers. These soft fronts offer fallback options and latent leverage in the event of escalation or diplomatic collapse.

Recent Case Studies (2022–2025)

Iraq and Syria: Attacks on U.S. Targets

Since early 2022, Iranian-backed militias in Iraq and Syria have escalated attacks on U.S. military positions. Groups like Kata’ib Hezbollah, Harakat al-Nujaba, and Liwa al-Tufuf use rockets, mortars, and loitering munitions with increasing frequency. U.S. bases in Erbil, Ain al-Asad, and al-Tanf have been repeatedly targeted—often after Israeli strikes or U.S. sanctions announcements. These militias receive equipment, intelligence, and battlefield guidance from Quds Force personnel embedded in Abu Kamal and Jurf al-Sakhar command cells.

Although damage remains limited, the attacks serve Iran’s strategic purpose: applying pressure without inviting direct retaliation on Iranian territory. Each strike acts as a pressure valve, signaling Tehran’s discontent and deterring deeper Western involvement. The violence also shifts diplomatic momentum and complicates U.S. basing negotiations. In response, the U.S. has launched airstrikes on militia depots and logistics hubs. Yet Iranian-linked groups often recover quickly, dispersing their assets and re-emerging with new names, leadership, or regional cover. This cycle illustrates the resilience of Iran’s proxy network and its mastery of attritional irregular warfare.

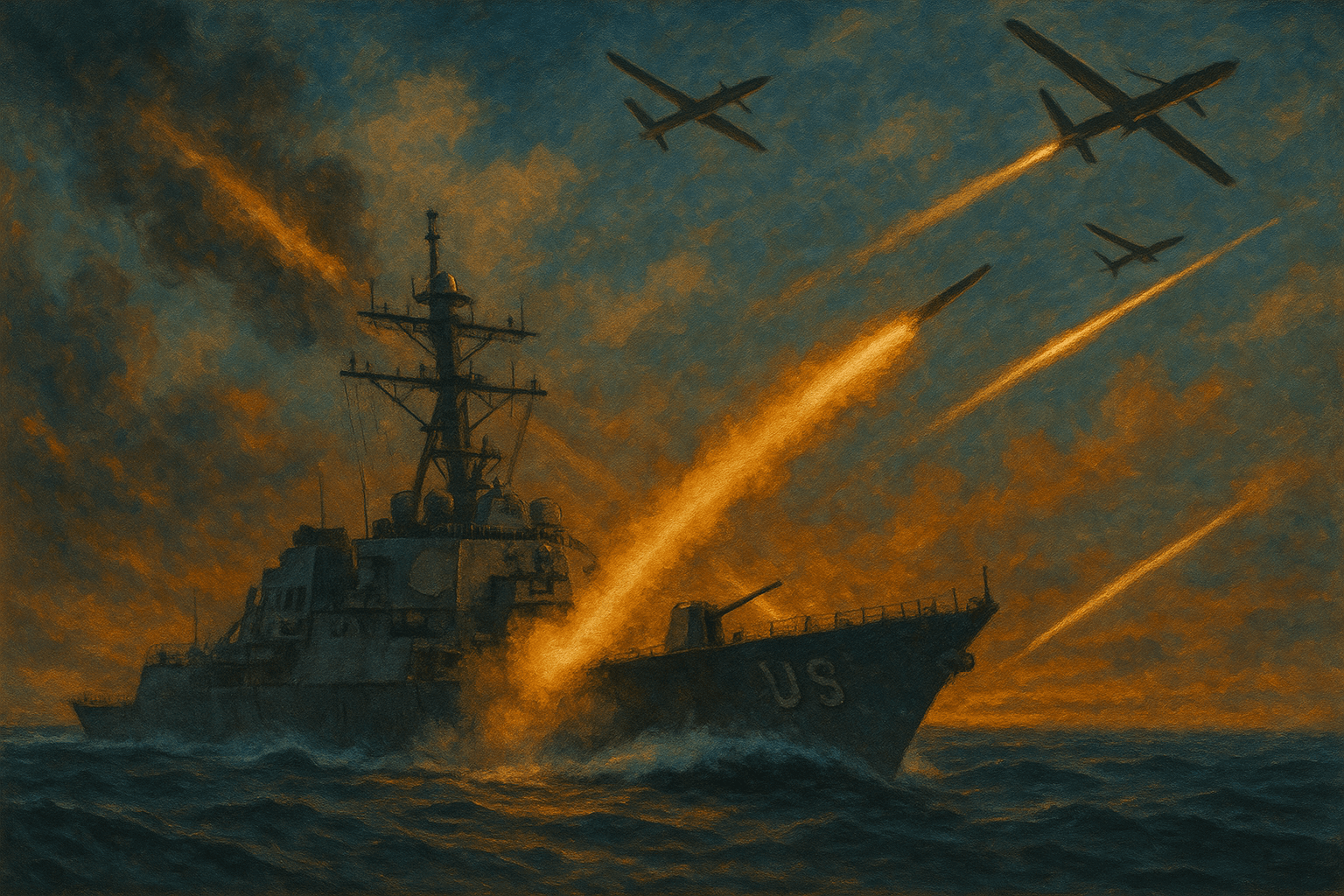

Red Sea Drone Escalation

By late 2023, the Houthis had expanded their drone and missile operations from the Saudi front into the Red Sea, threatening global shipping lanes. Dozens of vessels—some linked to Israeli firms, others flying neutral flags—were attacked near the Bab el-Mandeb Strait. The strikes used one-way explosive drones and anti-ship cruise missiles modeled on Iran’s Noor and Qader systems. Naval analysts noted increasing Houthi targeting sophistication, including coordination with satellite imagery and encrypted communications. Western intelligence agencies linked these advances to Quds Force advisers in Yemen. These advisers provided training, target lists, and battlefield assessments. The escalation prompted emergency deployments of U.S. and French naval forces. Insurance premiums for Red Sea commercial shipping spiked sharply. The campaign showed Iran’s ability to disrupt maritime trade through proxies while avoiding direct conflict with NATO forces.

Cyber Roils in Europe

In July 2024, a ransomware attack paralyzed parts of the German national railway system, halting trains and disrupting commerce. Forensic investigators linked the intrusion to APT33, an Iranian state-aligned cyber group known for targeting aerospace and energy firms. Analysts believe the timing—days after Berlin reaffirmed military aid to Israel—was intentional, not coincidental. The malware was disguised as a system update, exploiting old vulnerabilities in Deutsche Bahn’s internal network. Within weeks, Italy and Spain experienced blackouts affecting regional power grids, also linked to Iranian cyber actors. These events marked a shift: Iran’s cyber campaigns now targeted critical infrastructure, not just espionage or minor disruptions. The scope and coordination of the attacks suggested growing professionalism. Their success reinforced Iran’s digital strategy of asymmetric escalation.

Diaspora Assassination Attempts

Between 2022 and 2023, intelligence services uncovered multiple plots targeting Iranian dissidents living in Europe. In Germany, federal police arrested a Ministry of Intelligence (MOIS) operative carrying cyanide capsules, burner phones, and forged Polish passports. These were intended for assassinating a Berlin-based activist linked to a Kurdish opposition group. Another plot in Düsseldorf involved luring a female journalist to a “repatriation interview” at an Iranian consulate. That meeting was designed to facilitate her disappearance.

German counterintelligence reports concluded that Tehran had authorized a limited campaign of transnational repression. These tactics mirror those previously used in Turkey and Iraq. The assassination attempts aim to eliminate regime critics and intimidate the broader diaspora. The message is clear: no one is beyond the regime’s reach. Despite arrests and expulsions, MOIS continues testing Europe’s resolve. It uses front organizations and third-party assets to pressure Iranian exile communities.

Strategic Calculus: The Cost of Covert Power

Proxy-based irregular engagement offers Tehran a highly adaptive and cost-efficient strategy. It enables Iran to pursue its foreign policy objectives with flexibility, deniability, and minimal conventional exposure.

Scalability and elasticity are key advantages

Iran can adjust pressure based on the geopolitical environment. It escalates through drone attacks, cyber disruptions, or rocket fire. It de-escalates through restraint, recalls, or quiet backchannel talks. This flexibility lets Tehran respond to Western policy changes, regional unrest, or internal shifts. Denial capability remains a core pillar of the strategy.

Denial capability remains a core pillar of the strategy

Most Iranian-linked operations are designed to be unattributable or ambiguously claimed. Cyberattacks are traced to shell groups, and missile strikes originate from Houthi-held areas. Tehran maintains plausible deniability to avoid confirming direct state involvement. This ambiguity complicates any military response. Deniability insulates Iran from retaliation that might follow clear, overt aggression.

Regional influence is amplified through empowered affiliates

Iran does not merely support militias—it shapes their strategic orientation. This is evident in Iraq, where Tehran leverages Shia militias to influence cabinet formation, legislative decisions, and energy contracts. In Lebanon, Hezbollah serves as both a deterrent and a soft-power vehicle. In Yemen, Iranian support helps the Houthis project power against Gulf rivals, harass Red Sea shipping, and undermine Saudi-led diplomacy.

Risk transference further protects the regime.

Should a proxy provoke a major crisis, Western states must confront non-state actors with deep local roots—not IRGC regulars. This strategic buffer delays escalation, complicates attribution, and absorbs strikes that might otherwise hit Iranian soil. It also creates diplomatic friction, forcing states to weigh civilian risk and host-nation sovereignty. Proxies can retreat, rebrand, or splinter under pressure, making decisive victory elusive. Iran benefits from this ambiguity, maintaining influence without directly exposing its forces. Even when proxies are weakened, Tehran can regenerate them or redirect efforts elsewhere. This resilience makes proxy warfare a durable and adaptive pillar of Iran’s irregular strategy.

However, significant vulnerabilities persist.

Proxy blowback is a growing concern

Groups like Hezbollah or Kata’ib Hezbollah may pursue independent agendas, especially when local interests diverge from Tehran’s strategic calculus. Uncoordinated attacks can provoke disproportionate retaliation, destabilize relationships, or undermine diplomatic efforts.

Counter-cyber escalation is another risk vector

As Iranian cyber operations grow bolder, adversaries have responded with covert sabotage, such as the Stuxnet attack on nuclear facilities. They’ve imposed sanctions on IRGC-aligned firms and developed large-scale digital defenses. These efforts aim to limit Iranian access in future campaigns. Some governments have also enhanced public-private partnerships to defend critical infrastructure. Intelligence-sharing agreements, joint cyber exercises, and resilience planning have become standard tools for managing persistent Iranian intrusion attempts. While Tehran continues adapting, the growing costs and obstacles may constrain its operational freedom over time.

Reputational costs are cumulative

Each assassination plot, drone strike, or cyber intrusion deepens Iran’s global isolation. The U.S., EU, Gulf States, and Israel are expanding cooperation on counter-IRGC strategies. These range from sanctions enforcement to joint cybersecurity initiatives and maritime interdictions. Multinational task forces are now tracking proxy movements, financial flows, and arms transfers in real time. Intelligence fusion centers have improved coordination, reducing the gaps Iran once exploited. Several countries have updated laws to criminalize material support to IRGC-linked entities. This growing web of pressure reflects a shift: Iran’s shadow campaigns no longer escape scrutiny—they increasingly trigger unified, preemptive countermeasures.

While Tehran’s irregular warfare model is tactically effective, its long-term sustainability is not guaranteed. The more Tehran leans on proxies, the more it risks strategic overextension, operational miscalculation, and international backlash.

What Comes Next? Outlook 2025–2028

The post-Hamas-Israel war era has emboldened Tehran. Iranian security chiefs see an opportunity: the fragility of Western political consensus, U.S. overextension, and domestic polarization in Europe tilt the incentives toward expanded proxy strikes and cyber punishment.

Key projections:

- Expanded cyber targeting of U.S. critical infrastructure: Ongoing tensions may prompt waves of digital disruption rather than kinetic escalation.

- Militia refresh in Iraq: With U.S. sanctions easing and Hezbollah gains, Iran could consolidate its Iraqi foothold for potential political domination.

- Drone salvo proliferation: Commodity drone kits modified with Iranian tech may transform Gulf security dynamics, with hits on civilian aircraft or ports as salvos of provocation.

- Strategic overextension risks: A multiaxis strain—between Yemen, Iraq, and cyber fronts—could introduce fractures into Iran’s unified chain of command, inviting miscalculations.

Conclusion

Iran’s irregular warfare machinery is not an add-on to its military—it is a parallel structure of influence and denial. It fuses revolutionary ideology, state infrastructure, and covert operations into a networked, transnational framework. Iran has built a model of state-sponsored irregular warfare that is agile, layered, and resistant to traditional deterrence. By using proxies, sabotage, cyberattacks, and clandestine influence, Tehran conducts strategic activity in the shadows. Each part of this apparatus is designed for deniability and scalability.

Attacks are divided by geography and proxy, calibrated to avoid war while causing political, psychological, or economic cost. An assassination in Berlin, a drone strike in the Red Sea, and ransomware in Madrid are not isolated events. They are modular operations inside an integrated doctrine of coercive ambiguity. Iran will continue this strategy—the question is when, where, and through whom it strikes next. Tehran’s irregular arsenal is not fixed; it adapts to global tensions, new technologies, and domestic pressures.

For Western states and regional rivals, understanding Iran’s strategy is essential—not optional. Countering this irregular architecture requires more than deterrence—it needs a cross-domain response. This includes unraveling disinformation, fortifying cyber defenses, exposing logistics and finances, and undermining the legitimacy of proxies. Democratic resilience will depend on an anticipatory strategy and strong interagency coordination. The next attack may not be a missile barrage—it could be a proxy riot, a blackout, or a silenced voice abroad.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply