Mapping Resistance Networks: The Power of Social Network Analysis

Resistance movements, whether peaceful or armed, do not appear by chance. They grow, survive, or collapse based on the strength of the networks that connect them. Trust, communication, and influence are the foundations of these systems. Social Network Analysis (SNA) provides the framework to understand how those links operate, showing the hidden structures that shape every movement’s effectiveness and survival.

From clandestine guerrilla cells to decentralized protest organizations, SNA exposes how resistance networks build resilience under pressure. It helps explain why some endure in the face of repression while others fragment and fade.

The key questions are straightforward: What makes a network resilient? What vulnerabilities lead to its collapse? And how can analysts, strategists, and activists use this understanding to build or counter organized resistance?

The Hidden Influence of Social Networks

Nicholas A. Christakis — TED Talk

Why behaviors and ideas spread through networks, and why influence often travels up to three degrees of separation. Useful context for resistance networks and Social Network Analysis.

The Basics: How Social Networks Work

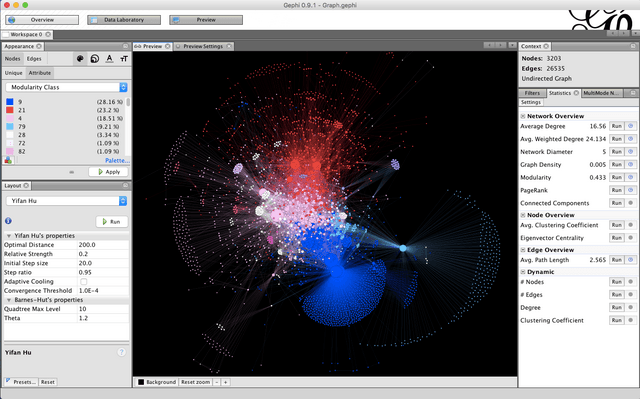

At its core, Social Network Analysis (SNA) is about mapping connections. Imagine a web where nodes represent individuals, groups, or organizations, and edges mark the relationships that link them. These visual maps reveal who holds influence, how information moves, and where weak points may exist.

Key Network Concepts

Directed and Undirected Networks:

In resistance movements, some connections follow hierarchy, with orders flowing from leaders to foot soldiers. Others operate on mutual trust among equals. The balance between these structures affects how flexible and resilient a movement becomes. In a well-organized insurgency, commanders issue guidance that moves through defined layers of leadership, forming a directed network. Activist movements, by contrast, often rely on cooperation without formal hierarchy, creating an undirected network. The French Resistance during World War II used a combination of both models: regional leaders received intelligence from London while collaborating with loosely connected cells to carry out operations.

Ego Networks and Whole Networks:

Studying one individual’s connections, or their ego network, can reveal much about their influence and function. Analyzing the whole network exposes overall strengths and vulnerabilities. Picture a local labor organizer who knows key figures in several unions. Their personal network might bridge otherwise separate groups, allowing coordination that would not occur naturally. When viewed at the movement level, the network may show strong clusters in some areas but isolation in others—a structural weakness that can hinder communication or planning.

These fundamentals establish the foundation for deeper analysis. In resistance, who you know and how you are connected often determine whether a movement endures or collapses under pressure.

Measuring Power and Vulnerability in Resistance Networks

Understanding who holds power and how influence circulates is central to analyzing any resistance network. Social Network Analysis (SNA) goes beyond charting connections; it helps explain how authority, trust, and coordination operate within movements. By identifying key individuals and relationships, analysts can predict which nodes sustain resilience and which create risk.

Centrality Measures: Who Holds the Power?

Degree Centrality:

The individuals with the most connections often occupy leadership, logistics, or communication roles. Gandhi in the Indian independence movement exemplified this principle. He served not only as a symbol but as the hub linking diverse factions. In a digital age context, an activist with a large following may not control decisions directly, yet their ability to spread information gives them substantial influence.

Betweenness Centrality:

Some figures act as bridges between groups, maintaining coordination across lines of distrust or distance. T. E. Lawrence performed this role during the Arab Revolt, connecting dispersed tribes and commanders. In a resistance network, if one respected intermediary unites multiple factions, their removal through arrest, assassination, or defection can cause the entire structure to fragment.

Eigenvector Centrality:

Influence also depends on being connected to other powerful actors. Charismatic leaders and ideologues often derive their reach not only from their own followers but from their access to other centers of power. Martin Luther King Jr. exemplified this dynamic. His influence extended through relationships with churches, student movements, and political organizations, multiplying his ability to shape outcomes.

These measures reveal more than hierarchy. They expose the pathways through which influence, trust, and information travel—the true arteries of resistance networks. Recognizing these dynamics allows analysts and strategists to understand where movements draw their strength, how they adapt under pressure, and where intervention or reinforcement can have the greatest impact.

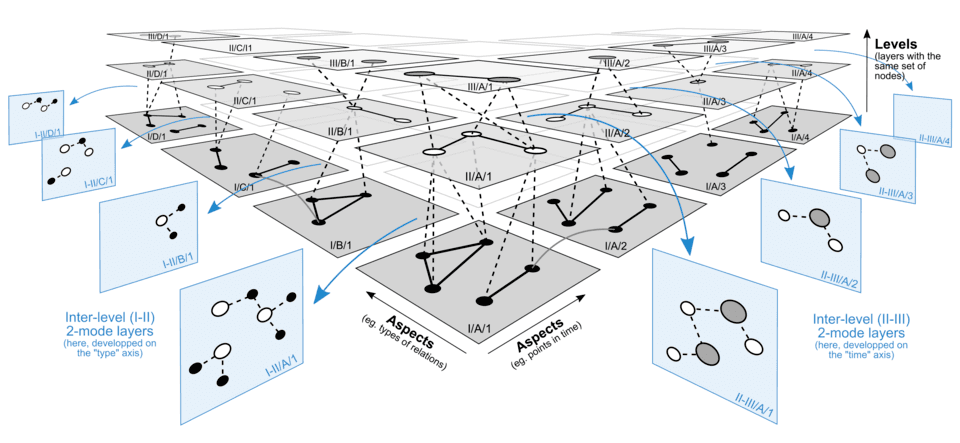

Network Resilience and Weaknesses

The structure of a resistance network determines how well it can endure stress, recover from losses, and maintain operational control. Social Network Analysis (SNA) provides several ways to measure resilience, revealing the tradeoffs between security, communication, and adaptability that every movement must balance.

Density:

Tight-knit groups are harder to dismantle but more vulnerable to infiltration once compromised. Loose networks are easier to conceal and reconfigure, yet they often struggle to coordinate complex actions. Al-Qaeda’s early decentralized model demonstrated how flexible structures can sustain activity despite leadership losses. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) combined both approaches, using dense local cells for operational security and looser political networks for broad mobilization.

Clustering Coefficient:

Resistance cells often cluster closely to protect information and identity. This enhances security but slows communication and innovation. Picture a network of environmental activists who communicate only within their immediate circles. The compartmentalization keeps them safe, yet it limits their ability to adapt rapidly or coordinate responses across regions.

Network Diameter and Path Length:

When communication chains are long, efficiency suffers. Che Guevara’s Bolivian campaign illustrates this limitation. His units were isolated, struggled to communicate with local supporters, and failed to adjust tactics as conditions changed. Shorter paths between nodes generally improve responsiveness and cohesion under pressure.

These structural metrics reveal why some movements survive disruption while others collapse. They remain relevant in the modern era, shaping how both resistance and counter-resistance actors organize, communicate, and evolve in dynamic operational environments.

The Anatomy of Resistance Networks

The structure of a resistance network determines how it operates, adapts, and survives under pressure. Its shape reveals both its strengths and its potential vulnerabilities. Social Network Analysis (SNA) helps identify how cohesion, communication, and control interact within these structures, shaping how a movement functions in the field or online.

Homophily and Community Detection:

Movements often form around shared identities such as political ideology, religion, or social purpose. This natural tendency, called homophily, strengthens trust and solidarity within the group. The U.S. Civil Rights Movement, for example, relied heavily on church networks that provided both moral legitimacy and logistical support. These common bonds enable collective action but can also limit outreach if a network becomes too insular.

Cliques and Subgroups:

Small, close-knit cells often serve as the backbone of a resistance network. They provide security, enforce discipline, and allow operations to continue even when higher structures are disrupted. During World War II, the underground movements in Nazi-occupied Europe relied on semi-independent cells that could act autonomously if neighboring networks were compromised. This design made them difficult to eradicate but sometimes slowed the spread of information between regions.

Structural Holes and Bridges:

Some leaders or intermediaries occupy the gaps between groups, controlling the flow of information and coordination across the broader movement. These bridges can amplify influence, unify disparate factions, and accelerate decision-making. However, they also become critical points of failure if removed. In modern contexts, social media figures who connect distinct activist communities often shape a movement’s public narrative and strategic direction.

Robert Taber’s The War of the Flea illustrates the delicate balance between autonomy and coordination. Excessive independence can lead to fragmentation, while heavy centralization creates predictable patterns that adversaries can exploit. The most durable resistance networks find equilibrium—strong enough to coordinate action, yet flexible enough to adapt when disrupted.

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Social Network Analysis (SNA) is a powerful tool for understanding how resistance networks operate, but its use carries serious ethical implications. The same methods that reveal organizational strength and vulnerability can also expose individuals to risk. Analysts, researchers, and activists must weigh the value of insight against the potential harm that disclosure can cause.

State Surveillance:

Governments increasingly use SNA to monitor, disrupt, or manipulate resistance networks. The distinction between security and repression often depends on how this capability is applied. In several authoritarian contexts, state actors have used network-mapping technologies to identify, track, and neutralize opposition figures. China’s monitoring of pro-democracy activists in Hong Kong demonstrated how advanced data analytics can dismantle decentralized movements by targeting key connectors rather than large groups.

Bias in Network Mapping:

Quantitative models can distort reality if they ignore cultural and contextual variables. Not every link in a network carries equal weight. A formal tie documented through communication logs may matter less than a personal relationship built on years of trust. Failing to account for these qualitative dimensions can lead to flawed conclusions and poor strategic decisions. For researchers or military planners, understanding human context is as important as statistical accuracy.

Ethical Use of Data:

Those studying or supporting resistance movements must protect the very people their work seeks to understand. Publishing or sharing detailed network maps can unintentionally expose participants to surveillance or arrest. Some organizations have responded by creating decoy or compartmented networks that obscure real connections. Such measures require careful planning to avoid confusion within the movement while maintaining operational security.

Social Network Analysis offers deep insight into resistance dynamics, but its application must be tempered by responsibility. Mapping power without safeguarding people risks turning a diagnostic tool into an instrument of harm. Ethical awareness is not an obstacle to analysis—it is part of what ensures that analysis serves justice rather than oppression.

Final Thoughts: The Power of Networks in Resistance

Social Network Analysis (SNA) shows that resistance is never random; it is relational. Movements survive not because they are the strongest, but because their internal connections allow them to absorb shocks, rebuild, and adapt faster than the systems opposing them. Every successful campaign, from the French Resistance to the digital activists of Hong Kong, has relied on networked structures that balance secrecy with communication, and autonomy with coordination.

Understanding these patterns turns abstract theory into operational insight. For analysts and policymakers, mapping networks exposes both vulnerabilities and opportunities for engagement. For activists, it highlights that resilience depends less on charismatic leadership and more on distributed trust, redundancy, and shared purpose.

In this light, resistance functions as a living system that organizes itself, learns, and evolves. Its strength lies not in weapons or slogans but in relationships built across lines of fear and division. As Robert Taber observed in The War of the Flea, power resides in the connections that can outlast repression. The study of resistance networks is therefore not only a window into past struggles but also a guide for understanding how modern societies resist domination, coordinate change, and sustain hope under pressure.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply