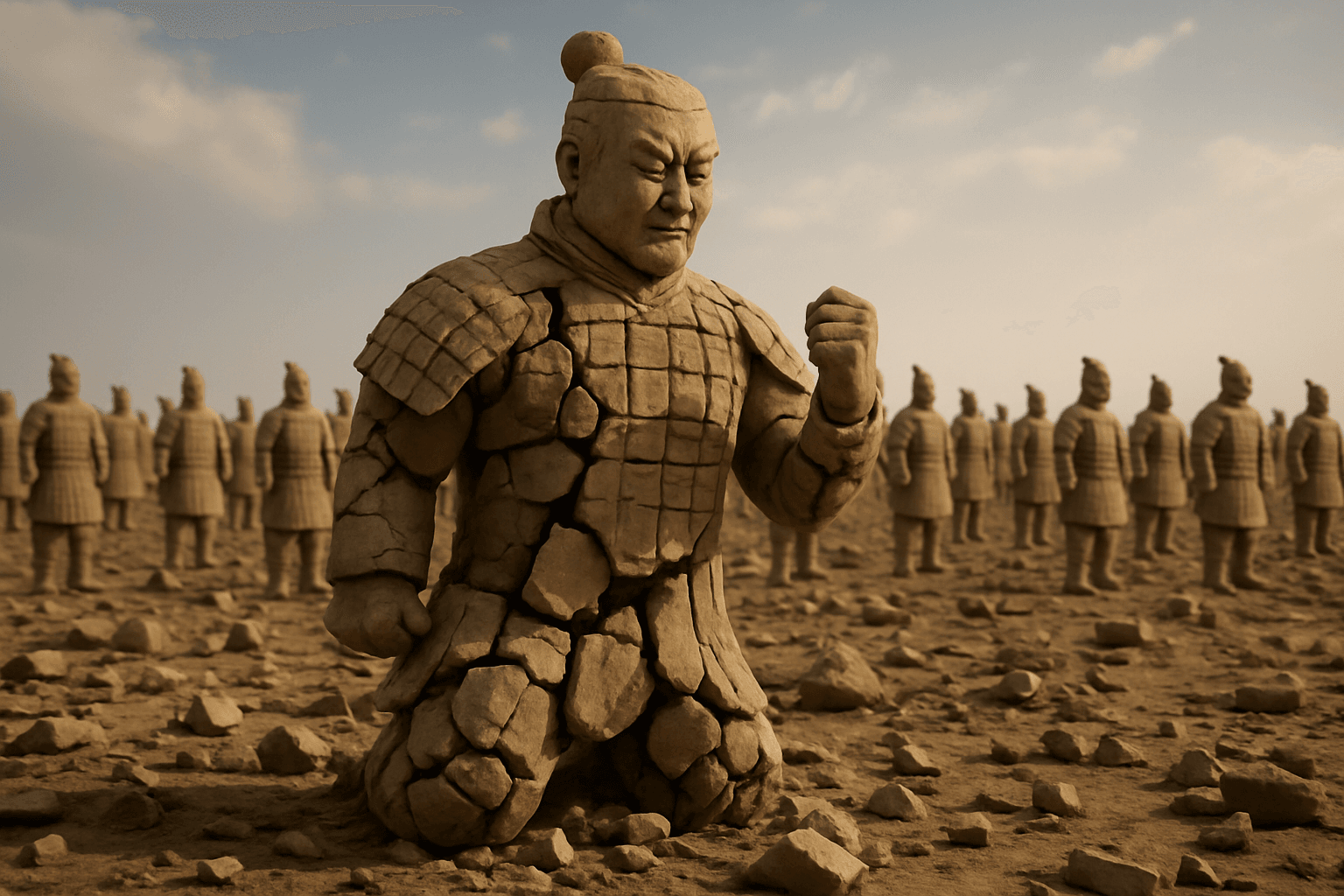

From the outside, authoritarian militaries project order, strength, and cohesion. Flags wave. Ranks shine. Parades thunder with disciplined force. But beneath the surface of tightly controlled structures like China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and Russia’s Armed Forces lies a brittle foundation — one that irregular warfare is uniquely suited to exploit.

Despite overwhelming firepower and state control, these militaries are built on rigid command systems, service compartmentalization, and political oversight that suppress battlefield initiative and adaptability. In the age of distributed, hybrid, and irregular threats, such traits are less a strength than a liability.

This article explores why highly politicized and service-compartmented militaries like China’s and Russia’s are increasingly vulnerable to irregular warfare — not just tactically, but structurally.

Command by Loyalty: The Anatomy of Politicized Military Hierarchies

The central feature of both the PLA and Russia’s armed forces is not just hierarchy — it is political hierarchy. In authoritarian systems, the military is not an autonomous instrument of national defense. It is a political organ, designed to serve and uphold party power above all else.

China’s Dual-Command System

In the PLA, command is split between military officers and political commissars. Every unit, from the company level upward, includes both a military commander and a party representative — the political officer. These dual chains of command prioritize ideological purity, discipline, and control. Decisions must be aligned not just with tactical goals but with the political needs of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP).

This structure creates a built-in lag between battlefield conditions and response. Officers are evaluated not solely on performance, but on political reliability. Decision-making is cautious, rehearsed, and deeply centralized in irregular warfare environments — where ambiguity, speed, and initiative matter — this system is dangerously inflexible.

Russia’s Legacy of Political Surveillance

Russia’s military operates under a less explicit dual-command system, but retains a long tradition of political control over military independence. The legacy of the Soviet Union’s GRU, political commissars, and purges still echoes in today’s structure. Modern Russian officers must navigate an environment where deviation from command is not innovation — it’s insubordination.

Since 2022, Russia has executed or removed numerous senior commanders due to battlefield failures. But those failures were often the result of structural rigidity, not incompetence. Russian command culture’s verticality made it unable to adapt to Ukraine’s decentralized, mobile, and irregular resistance.

Silos and Silence: Compartmentalization as a Strategic Weakness

Modern warfare requires integration across services, domains, and information systems. Yet both China and Russia continue to suffer from severe service compartmentalization, making them vulnerable to hybrid attacks, irregular disruption, and disjointed responses.

The PLA’s Walls Between Services

In 2015, China attempted to modernize its force by restructuring the PLA into five major service branches: the Ground Forces, Navy, Air Force, Rocket Force, and Strategic Support Force (cyber, electronic, and space operations). While this reorganization improved bureaucratic clarity, it exacerbated compartmentalization.

- Each service retains separate command hierarchies.

- Joint operations are underdeveloped and rarely exercised at scale.

- Real-world experience is minimal — the PLA has not fought a war since 1979.

This lack of integration is a liability in irregular warfare scenarios. A sabotage attack on a PLA radar facility, for example, might require a coordinated response from ground forces, cyber defense teams, and civilian power authorities—all operating under different command umbrellas.

Russia’s Dysfunctional Interoperability

Russia has long struggled with poor inter-service cooperation. In Ukraine, coordination between the Russian Army, Aerospace Forces, and Naval Infantry was often nonexistent. Units advanced without artillery support. Air defenses were deployed late or in the wrong locations. Electronic warfare teams jammed their own troops.

This lack of horizontal coordination allowed Ukraine — with its decentralized special forces, flexible logistics, and citizen intelligence networks — to fracture Russian coherence through irregular pressure.

Russian Fragility in Ukraine — and Before

Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 provides the clearest modern example of how a heavily centralized and politicized military can be outmaneuvered by a more agile, networked adversary using irregular methods. However, Ukraine is not the first time Russia’s rigid military model has collapsed under asymmetric pressure — it is only the most visible.

In Grozny, during both Chechen wars (1994–1996 and 1999–2000), Russian armored units were annihilated in urban environments after advancing without adequate infantry support or decentralized decision-making. Chechen fighters — lightly armed but highly mobile — exploited the gaps between services and overwhelmed Russian formations through ambushes, snipers, and IEDs. Russian command, rooted in vertical control, was slow to adapt and unable to empower junior leaders under fire.

In the 2008 Russo-Georgian War, despite Russia’s rapid victory, internal assessments revealed glaring deficiencies in inter-service coordination and real-time communications. Russian air and ground forces frequently operated in isolation, with units struggling to distinguish friend from foe. Georgia’s own use of electronic warfare and mobile counterattacks, while limited in scale, revealed how information disruption could paralyze a conventional force unused to ambiguity.

Going further back, during the Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989), Soviet forces repeatedly failed to suppress a decentralized mujahedin resistance. Despite air superiority and armor, Soviet troops lacked flexibility in terrain-dominated conflict zones. Afghan fighters used irregular tactics—mountain ambushes, supply disruption, targeted assassinations—to erode morale and expose Soviet vulnerability to irregular attrition. The Soviet command structure, deeply political and rooted in top-down orders, never adapted to the demands of counterinsurgency.

By the time Russia entered Ukraine in 2022, it had decades of evidence warning against its own structural rigidity. Yet the same systemic traits—compartmentalized services, limited NCO initiative, centralized command—remained, making its forces once again vulnerable to irregular pressure.

China’s Unproven Readiness: When Scale Becomes a Liability

While China has not yet faced an irregular war in modern times, its internal structure and exercises reveal the same systemic flaws that undermined Russian operations. However, in China’s case, the scale of a potential military operation — especially one as complex as a Taiwan invasion — adds a new dimension of vulnerability.

Scale brings inherent complexity. Conducting a cross-strait amphibious assault would require China to coordinate tens of thousands of troops across multiple domains: air, sea, cyber, electronic warfare, logistics, and civil affairs. This would demand an unprecedented level of joint integration — something the PLA has little real-world experience executing.

Despite reforms, the PLA remains functionally compartmented. Each branch — Ground Forces, Navy, Rocket Force, Air Force, Strategic Support Force — maintains its own planning culture, command hierarchy, and logistical chain. Even if the operation succeeds in its opening phase, sustaining momentum in the face of resistance or disruption becomes significantly more difficult.

Irregular disruption in such a context doesn’t need to be decisive to be effective. Limited sabotage of radar sites, insertion of false signals, psychological operations targeting commanders, or SOF raids on logistics hubs could inject additional chaos into an already complex battlespace. These frictions multiply in value when layered over an unpracticed joint force. A drone swarm may not sink a warship, but if it delays a beach landing or jams comms at a critical moment, the strategic impact can be enormous.

In essence, the larger and more complex the operation, the more susceptible it becomes to localized irregular resistance. China’s overwhelming scale may become a liability, not because of enemy parity but because of internal friction magnified by asymmetric disruption.

Why Irregular Warfare Exploits Centralized Militaries

Irregular warfare is not only a contest of firepower — it is a contest of tempo, trust, and structure. It thrives on ambiguity, decentralization, and initiative, which makes it uniquely effective against militaries that rely on centralized command, rigid discipline, and politically sanitized decision-making.

Authoritarian systems like those in China and Russia are built to prevent deviation and not to adapt under pressure. Each of their structural traits creates an opening, and irregular actors are ideally suited to exploit them:

Vulnerabilities:

- Rigid Command Hierarchies → Tactical Disruption via Sabotage or Multi-Axis Pressure

When decisions must flow vertically, even minor delays can paralyze a unit. Coordinated ambushes, drone strikes, or multi-domain attacks in dispersed locations force the enemy to wait for instructions rather than act independently, creating gaps in time and space. - Fear of Initiative → Psychological Exploitation

Officers who fear punishment for unauthorized action are less likely to improvise. This can be weaponized through feints, false flag operations, or simulated threats that force the enemy to seek permission before reacting, buying critical time for irregular forces. - Compartmentalized Services → Layered Multi-Domain Attacks

Lack of jointness allows multi-domain disruption to fracture cohesion. For example, cyberattacks against logistics paired with electromagnetic interference against targeting radars can overwhelm stovepiped services that cannot coordinate rapid countermeasures. - Overcentralized C2 Nodes → Decapitation via SOF or Partisan Sabotage

Authoritarian systems often concentrate decision-making and coordination in a handful of command centers. Irregular teams can target these nodes — whether physically (raids, IEDs) or digitally (cyber intrusion, GPS spoofing) — to cripple operational continuity. - Politicized Messaging Discipline → Information Operations to Sow Doubt

In tightly controlled regimes, commanders rely on party-approved messaging to guide troops. If irregular forces can inject doubt into these channels — through deepfake videos, intercepted communications, or credible disinformation — they can erode confidence in orders. In a high-stakes operation like a Taiwan landing or Baltic incursion, even hesitation can be fatal. - Lack of Combat-Proven NCO Corps → Exploiting Friction in Chaos

Without experienced non-commissioned officers to stabilize units under pressure, irregular disruption magnifies disarray. Ambushes, small-unit raids, and sudden terrain denial (like bridge demolitions or terrain shaping) can create disorder that no officer-heavy structure can easily reassemble in the field.

How To Leverage?

In total, irregular warfare turns authoritarian military design principles against themselves. It does not need to win through symmetric confrontation. It only needs to exploit internal contradictions long enough to stall objectives, disrupt tempo, and erode confidence. This includes undermining their adaptation speed and rapid decision-making under pressure. When faced with rigid hierarchies, irregular forces can seize the initiative. They set the tempo, dictate the terms of engagement, and force adversaries into reactive postures. Flexibility, decentralization, and local knowledge become strategic advantages. Over time, the burden of overextension and uncertainty wears down even the most technologically advanced or numerically superior forces.

Strategic Implications for Resistance Movements and Western Military Planning

Understanding the internal vulnerabilities of highly politicized, centralized militaries isn’t just theoretical — it’s strategic intelligence. For resistance planners and Western military advisors, these structural traits offer points of leverage in any future conflict or occupation scenario involving authoritarian adversaries.

Irregular warfare is most effective not when it tries to mirror the enemy’s strengths, but when it targets their bureaucratic pressure points and disrupts their cohesion from below. This requires a mindset shift: from destroying hardware to degrading command systems, morale, and tempo.

For Resistance Movements and SOF Advisors:

- Focus on Tempo Disruption

Authoritarian militaries need tempo to execute large, complex operations. Irregular forces can use sabotage, terrain denial, and multi-pronged pressure to force hesitation. A delayed bridge crossing or disrupted radar synchronization may derail entire operations timed for political symbolism. - Exploit Fear of Initiative

Resistance networks can weaponize the political caution embedded in the enemy officer corps. Simulated threats, decoys, or ambiguous actions can create paralysis among mid-level commanders trained not to act without approval. - Target the Connective Tissue

Jointness — or the lack thereof — is a weakness. Cyber operations that isolate one branch (e.g., jamming Rocket Force communications) or disable cross-domain logistics (e.g., rail sabotage) can fracture command unity. These are asymmetric operations with outsized impact. - Invest in Perception Warfare

Civil resistance and information operations can exploit the enemy’s dependence on narrative control. Deepfake orders, doctored videos, or even subtle disruptions of information trust between command echelons can erode cohesion faster than kinetic strikes. - Decentralize Early and Often

Resistance cells must avoid mirroring the structure of the enemy. Independent action, mission command principles, and horizontal intelligence sharing allow them to survive and outpace a slower, politically entangled force.

For Western Military Planning:

- Train for Fluidity, Not Just Firepower

Partner forces should be trained not only in combat but in adaptive planning, improvisation, and small-unit autonomy. Mission command isn’t just a doctrine — it’s a strategic antidote to authoritarian rigidity. - Support Indigenous Irregular Capabilities

In places like Taiwan, the Baltic States, or Southeast Asia, irregular warfare must be embedded into civil defense. Arming a population is not enough—they must be trained to see structure as the target and friction as their ally. - Build Hybrid Layered Defense

Modern deterrence must integrate SOF, cyber teams, information operators, and civilians in a cohesive resistance strategy. Against a brittle, top-heavy force, a flexible and layered irregular network can apply pressure where the enemy can’t respond. - Prepare for Psychological Decoupling

One of the most under-discussed irregular advantages is the ability to disrupt trust inside the enemy’s command environment. If a PLA unit questions its orders, or a Russian brigade hesitates to act due to mixed signals or digital noise, the tactical advantage shifts without a shot being fired.

This is the future of resistance and irregular warfare—not just asymmetric in tools but also asymmetric in thought. In that realm, rigid military cultures are not prepared to win.

Fragile Giants in the Age of Irregular War

Authoritarian militaries’ image of strength can be deceiving. Their parades, precision, and party loyalty disguise an uncomfortable truth: their greatest weakness is structural. In systems where initiative is punished, information is tightly controlled, and services are siloed, battlefield adaptability becomes a liability, not a capability.

Russia’s failures in Ukraine exposed the costs of brittle command and political interference. China, for all its modernization, risks repeating these mistakes at an even greater scale. A force that cannot improvise under pressure, cannot coordinate across domains, and cannot trust its officers’ initiative is primed to falter when confronted by irregular resistance.

Irregular warfare does not seek to match authoritarian power — it seeks to unravel it. It turns complexity against itself. It reminds us that in the age of hybrid war, decisive battles may not be fought with tanks or missiles but with ambiguity, disruption, and quiet erosion of control.

For those preparing to resist, support, or understand the next great conflict, the lesson is clear: know your adversary’s structure and break it where it cannot bend.

Sources & Further Reading

- Chechnya and Urban Warfare:

- Grau, Lester W., and Timothy L. Smith. Urban Combat: Confronting the Specter of Chechnya. Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth.

- “The Battle of Grozny: Deadly Urban Combat.” BBC News, 1995.

- Russo-Georgian War (2008):

- Asmus, Ronald. A Little War That Shook the World: Georgia, Russia, and the Future of the West. Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

- “Russia’s Armed Forces on the Path of Reform.” International Institute for Strategic Studies, The Military Balance, 2009.

- Soviet-Afghan War (1979–1989):

- Russian Military Failures in Ukraine:

- United Kingdom Ministry of Defence, Intelligence Updates. (2022–2023). gov.uk

- CSIS Reports: “The Military Lessons from Ukraine” – Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2023.

- Kofman, Michael & Lee, Rob. Lessons from the Russo-Ukrainian War. Foreign Affairs, 2023.

- PLA Structure and Weaknesses:

- U.S. Department of Defense. Annual Report to Congress: Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China. 2023.

- Fravel, M. Taylor. Active Defense: China’s Military Strategy since 1949. Princeton University Press, 2019.

- Mulvenon, James. “PLA Organizational Reforms and the Joint Operations Puzzle.” RAND Corporation.

Doctrine & Irregular Warfare Theory

- Taiwan Defense and Irregular Planning:

- Information Operations & Disruption:

- NATO StratCom Centre of Excellence. Hybrid Threats and Influence Operations in the Digital Domain. 2022.

- “How Ukraine Won the Information War Against Russia.” Financial Times, June 2022.

- Comparative Command Models:

- Scales, Robert H. Certain Victory: The U.S. Army in the Gulf War. Office of the Chief of Staff, U.S. Army, 1994.

- U.S. Army Field Manual 3-24. Insurgencies and Countering Irregular Threats. Department of the Army, 2021.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply