The Complex Art of Mobilizing Resistance Movements: Barriers, Violence Thresholds, and State Repression

From Belarus to Iran to Myanmar, movements for freedom continue to rise under repressive conditions. Some capture global attention, while others fade in silence, crushed before they mature. The pattern is familiar yet never predictable. Resistance movements can topple regimes, expose corruption, and redraw political maps—but mobilizing people to join them remains one of the hardest challenges in political life.

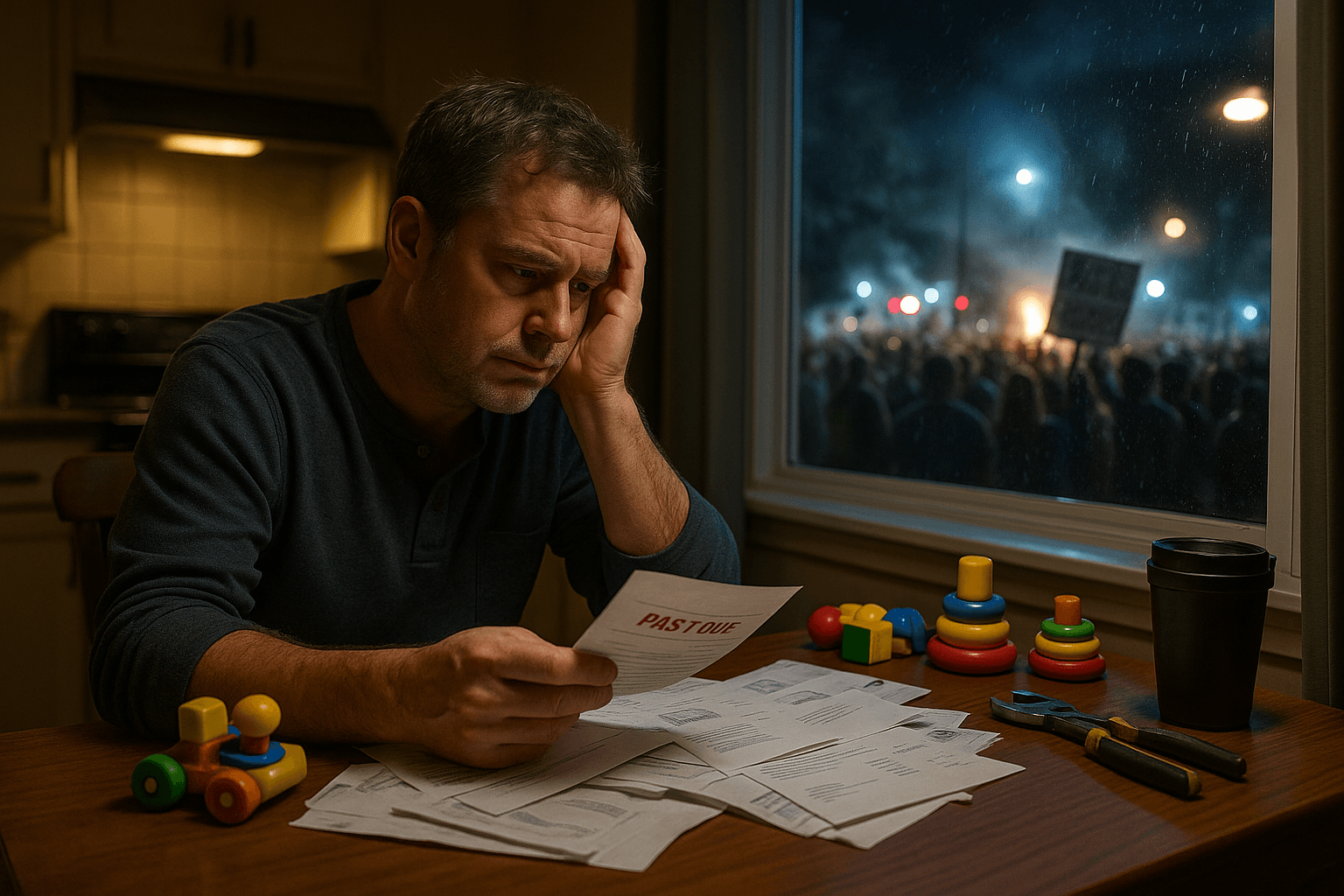

At the heart of every movement lies a fundamental problem: how to turn private discontent into collective action. Most citizens may share grievances, but few are willing to risk their safety, livelihoods, or families to act on them. States exploit this hesitancy through economic control, surveillance, and selective punishment. Fear and dependence keep populations compliant, even when outrage simmers beneath the surface.

When resistance finally takes shape, it triggers a dynamic confrontation. The state escalates repression, movements adapt, and the balance of fear begins to shift. Success or failure depends on whether the resistance can overcome barriers to participation, navigate the threshold between nonviolence and armed struggle, and survive the cycle of repression that follows every act of defiance.

This article examines those three dynamics in detail—the barriers to participation, the societal threshold for violence, and the repression–mobilization cycle—to explain why some resistance movements endure while others collapse. Understanding these forces is not only an academic exercise. It is a blueprint for how power resists change, and how those seeking justice can learn to outlast it.

Understanding why resistance struggles to begin requires examining the first of these three dynamics: the barriers that keep people from joining even when injustice is clear.

Barriers to Participation: Why People Hesitate to Join

Mobilizing large-scale resistance is never as simple as rallying people around a cause. Structural, psychological, cultural, and logistical constraints determine whether potential supporters stay passive or take the first risky step toward collective action. Across regions and regimes, these barriers reveal how systems preserve control not only through force but through dependence and fear.

Structural Barriers: When the System Works Against You

James C. Scott, in Weapons of the Weak, demonstrates how economic dependence shapes compliance. In agrarian Malaysia, tenant farmers relied on landlords who also controlled access to credit, tools, and markets. Challenging authority meant risking starvation. The same dynamic persists today in authoritarian and semi-authoritarian states where employment, housing, or food subsidies depend on political loyalty.

Mancur Olson’s Logic of Collective Action adds another dimension: the free rider problem. When individuals believe others will shoulder the cost of activism, they rationally opt out. Modern digital movements encounter the same logic. Clicking “like” or sharing a post creates the illusion of participation, allowing many to signal dissent without real exposure to danger.

These structural traps explain why quiet forms of defiance—work slowdowns, selective noncompliance, and minor sabotage—often precede open rebellion. They offer the only outlet for populations locked in economic or bureaucratic dependency.

Psychological Barriers: Fear and Self-Doubt

Repression relies as much on psychology as it does on policing. Fear of imprisonment, job loss, or social isolation discourages dissent long before violence begins. Albert Bandura’s concept of self-efficacy is central here: individuals must believe their actions can influence outcomes. When they cannot visualize success, they retreat into apathy or survival behavior.

Herbert Kelman’s research on conformity shows how deeply obedience becomes internalized. In societies where submission to authority is moralized through schooling, religion, or propaganda, defiance feels not only dangerous but wrong. That conditioning shapes how citizens in places like North Korea, China, or pre-revolutionary Egypt internalize hierarchy even in private thought.

Yet when fear recedes—even briefly—collective courage can cascade. Studies of the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests found that participation surged not after calls for freedom but after mass arrests. Once people realized repression was indiscriminate, fear lost its strategic power.

Cultural and Social Barriers: Who Gets to Resist?

Social hierarchies determine who feels entitled to resist. Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of cultural capital, outlined in Outline of a Theory of Practice, explains how privilege shapes access to political agency. Education, networks, and confidence in one’s legitimacy influence participation as much as ideology.

Resistance movements that ignore these disparities risk exclusion. During the early stages of the Algerian War of Independence, women were largely sidelined. Later, as the war intensified, female combatants and couriers became essential to the FLN’s operations. The shift was not ideological but practical: success required mobilizing everyone.

The same lesson has reappeared in twenty-first century movements. From the women-led protests in Iran’s “Woman, Life, Freedom” uprising to youth-driven mobilization in Myanmar’s anti-coup resistance, inclusivity has proven to be a force multiplier. Movements that draw on multiple social strata adapt faster and endure longer.

Resource Barriers: The Logistics of Resistance

Even the most motivated movement falters without infrastructure. Gene Sharp, in From Dictatorship to Democracy, identifies three nonnegotiables for sustainable resistance: communication networks, leadership, and funding. These determine whether frustration becomes organization.

Poland’s Solidarity movement overcame resource scarcity in the 1980s through clandestine printing presses, underground unions, and international aid. Today, encrypted communication, diaspora crowdfunding, and open-source intelligence play similar roles. The Belarusian opposition’s digital exiles and Ukraine’s territorial defense volunteers both show how transnational resource networks can sustain resistance even when domestic capacity collapses.

Logistics remain the bridge between grievance and mobilization. Without it, even righteous anger dissipates.

Societal Threshold of Violence: When Resistance Turns to Armed Struggle

Every society carries an internal tipping point—the level of violence it will tolerate before legitimacy fractures and resistance hardens. This societal threshold of violence is shaped by memory, repression, and culture. It decides whether people remain committed to nonviolent tactics or conclude that force has become the only language power understands.

The Case for Nonviolence

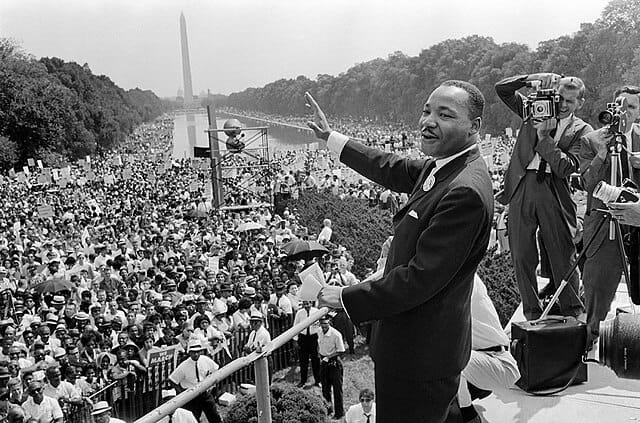

Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan, in Why Civil Resistance Works, present empirical evidence that nonviolent movements succeed more often than violent ones. Their dataset, spanning a century, shows that nonviolent campaigns are nearly twice as effective in achieving political change. The reason is pragmatic, not moral: nonviolence lowers barriers to entry. Far more people are willing to protest, strike, or boycott than to take up arms.

The U.S. Civil Rights Movement demonstrated how a high societal threshold for violence could be strategically harnessed. By maintaining nonviolence in the face of brutality, activists forced moral contrast and drew international attention. The imagery of peaceful protestors attacked by police dogs and fire hoses turned repression into recruitment.

Modern parallels exist. In Sudan’s 2019 revolution, nonviolent protestors faced lethal force yet refused escalation, preserving unity across ethnic and class lines. The result was the fall of a dictator—proof that restraint can be a weapon when visibility and moral legitimacy align.

Civil Resistance: Strategic Principles

Albert Einstein Institution — YouTube

A concise overview of the strategy behind nonviolent movements, drawn from the Albert Einstein Institution’s work on civil resistance and how organization scales under repression.

When Violence Becomes Legitimate

Yet history also reveals the limits of patience. Frantz Fanon argued in The Wretched of the Earth that colonial subjects live under structural violence so pervasive that armed resistance becomes a form of psychological liberation. Violence, in his view, reclaims dignity and agency long denied.

This rationale reappears wherever peaceful dissent meets unyielding repression. In Myanmar after the 2021 coup, student activists and former civil servants joined local defense forces when the regime began executing protestors. The shift from protest to armed resistance reflected not ideology but despair—an acknowledgment that the social contract was irreparable.

Hannah Arendt’s warning in On Violence still applies: violence retains legitimacy only while it is seen as necessary and proportional. When resistance crosses into indiscriminate attacks or internal purges, public sympathy evaporates. The moral boundary is not theoretical; it defines whether movements gain or lose the population’s trust.

Historical Tipping Points

India’s Independence Movement: Gandhi’s campaign for self-rule succeeded because it operated within a society with a high aversion to violence. By channeling discipline and noncooperation, the movement drew mass participation and eroded British authority without fracturing the population.

Algeria’s War of Independence: Colonial repression lowered Algeria’s threshold for violence until armed struggle became inevitable. As Alistair Horne recounts in A Savage War of Peace, both sides resorted to extreme brutality. Yet the war’s outcome reflected a core truth of irregular conflict: once violence becomes normalized, political compromise grows impossible.

Ukraine’s Resistance: Since 2014 and especially after the 2022 invasion, Ukraine’s population has endured repeated waves of violence, shifting its collective tolerance dramatically. Civilian participation in territorial defense, information operations, and sabotage networks shows how existential threat recalibrates a society’s willingness to fight. Violence ceased to be a last resort—it became survival.

When Frustration Boils Over

Ted Robert Gurr’s Why Men Rebel remains the definitive study on how unmet expectations drive conflict. When individuals believe they deserve better than what they receive—relative deprivation—anger transforms into political action. If peaceful channels are blocked, violence follows.

Gurr’s theory explains the sudden escalation of unrest in places like Sri Lanka (2022) and Iran (2022–2023), where economic collapse and corruption created the sense that the future had been stolen. When the perceived cost of inaction exceeds the cost of rebellion, the threshold for violence collapses.

The lesson is not that violence is inevitable but that it emerges from systemic failure. When citizens lose faith that change is possible within existing structures, violence becomes the substitute for politics.

The Repression-Mobilization Cycle: How Crackdowns Fuel Resistance

Repression is rarely a static act. It is a process—a rhythm of coercion, backlash, and adaptation that defines the trajectory of every resistance movement. States apply pressure to maintain control, yet that same pressure often forges unity among the oppressed. This paradox, known as the repression–mobilization cycle, explains why some governments collapse under the weight of their own crackdowns.

How the Cycle Unfolds

The pattern is consistent across time and geography:

- Initial Crackdown: Authorities deploy force, arrests, or surveillance to disrupt early organizing.

- Public Backlash: When repression is perceived as excessive or unjust, outrage spreads beyond activists to ordinary citizens.

- Expansion and Escalation: The resistance grows, adopts new tactics, and gains sympathy domestically or abroad.

Charles Tilly, in The Politics of Collective Violence, emphasized that repression can erode a regime’s legitimacy faster than open dissent. When people see power exercised without restraint, they begin to question not just the ruler’s methods but their right to rule.

Visibility: The Double-Edged Sword of Repression

Visibility determines whether repression silences or amplifies resistance. If crackdowns occur out of sight, they can effectively fragment movements. When they unfold under public scrutiny, however, they often trigger moral outrage that accelerates mobilization.

Michael Biggs’s research on protest fatalities demonstrates this effect. The 1960 Sharpeville Massacre in South Africa and the 1989 killing of demonstrators in Beijing’s Tiananmen Square both turned local grievances into global symbols. In each case, the state won the immediate battle but lost the international narrative.

In the digital era, visibility has become even more volatile. During the 2020 protests in Belarus, citizens livestreamed arrests and beatings across encrypted platforms. The regime’s violence no longer deterred dissent; it broadcast its own illegitimacy to millions. Repression failed because it could no longer be hidden.

Tactical Adaptation: Resistance Learns Faster Than Power

Repression forces innovation. Sidney Tarrow, in Power in Movement, argues that movements adapt by shifting tactics when violence backfires or opportunities emerge.

- When direct confrontation becomes too costly, movements pivot to low-risk acts—symbolic protests, economic noncooperation, or digital disruption.

- When peaceful channels close entirely, factions radicalize, forming clandestine cells or armed groups.

Modern examples illustrate both trajectories. In Hong Kong, protestors evolved from mass marches to decentralized flash mobs to evade surveillance. In Iran, women-led resistance adapted from public protests to digital campaigns using encrypted messaging and virtual networks. The state adjusted, but the movement evolved faster.

Case Studies: When Repression Backfires

South Africa, 1960–1990: The apartheid regime relied on lethal force to maintain control. Yet each massacre deepened international isolation and domestic radicalization. By the 1980s, repression had turned a labor dispute into a national liberation movement.

Tunisia, 2011: Mohamed Bouazizi’s self-immolation ignited protests that toppled a dictator. What began as an act of despair became a catalyst for the Arab Spring. The regime’s attempt to silence one man amplified the voice of millions.

Myanmar, 2021–2023: The junta’s brutality produced short-term paralysis but long-term insurgency. Civil servants, students, and ethnic minorities coalesced into a national resistance front. The repression–mobilization cycle completed itself: coercion created the unity repression sought to prevent.

Why Some Movements Break the Cycle

Not all repression breeds resistance. Success depends on three conditions:

- Information Flow: If the population remains isolated or censored, outrage dissipates before coordination forms.

- Organizational Depth: Movements with preexisting networks—unions, religious groups, diaspora channels—recover faster after crackdowns.

- Symbolic Resonance: When repression crystallizes into a shared moral narrative, it transforms fear into purpose.

The absence of these conditions explains why some uprisings fail quietly. The presence of all three explains why others reshape history.

Learning from History: Strategy, Resilience, and Execution

Mobilizing resistance is not a question of passion or ideology alone. It is an exercise in strategy—understanding when to act, how to sustain pressure, and when to adapt. History makes one thing clear: successful resistance movements align moral legitimacy with operational discipline.

Strategy Over Spontaneity

Movements that rely on emotion without structure rarely endure. Spontaneous uprisings can ignite awareness but struggle to maintain direction. Sustainable resistance requires coordination, logistics, and leadership resilient enough to survive repression.

The Polish Solidarity movement, India’s independence campaign, and the anti-apartheid struggle all shared this trait. Their success came not from a single protest or charismatic leader but from layered organization—networks that could absorb losses, rebuild, and adapt over time.

Modern resistance must think in similar terms. Movements facing digital surveillance, mass arrest, and disinformation require redundant systems—secure communications, encrypted storage, and international awareness campaigns—to preserve continuity when leadership is targeted.

Resilience Under Repression

Fear and fatigue are the state’s most reliable weapons. Repressive systems are designed to drain morale through uncertainty and isolation. Countering that requires social resilience—the ability to maintain trust, humor, and purpose even under surveillance or threat.

In Eastern Europe, underground presses once kept communities informed when official media was silent. Today, similar functions are carried out by digital platforms, anonymous accounts, and encrypted broadcasts. The form has changed, but the principle remains: information is oxygen for resistance.

Where regimes cut communication, solidarity networks abroad can bridge the gap. The Belarusian and Iranian diasporas demonstrate how external actors can sustain morale, document abuses, and channel funding long after domestic protests are crushed. Repression ends movements that cannot regenerate; resilience ensures they reappear in new forms.

Execution: Turning Ideals Into Action

Moral clarity without execution achieves little. Gene Sharp’s work reminds us that resistance is not chaos—it is a discipline. Planning, messaging, and timing determine whether a movement grows or fractures.

Effective movements combine three qualities:

- Moral coherence that maintains legitimacy.

- Operational discipline that prevents infiltration or collapse.

- Strategic patience that outlasts the state’s immediate advantage.

Understanding these dynamics turns resistance from impulse into institution. It is not about defiance for its own sake but about designing systems that can survive pressure.

The Enduring Lesson

History does not offer formulas, but it provides patterns. Barriers, thresholds, and repression will always shape the terrain of dissent. The difference between defeat and transformation lies in how movements interpret that terrain.

Resistance that endures is neither reckless nor naïve. It studies the systems it opposes, anticipates their response, and uses their rigidity as leverage. In every era—from anti-colonial struggles to digital-age defiance—the lesson remains constant: the fight for justice is not won by outrage, but by organization.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply