DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

The Resistance Hub

When the guns fall silent, the battle for a country’s future begins. The history of post-conflict transitions shows that what happens after the fighting can be as decisive as the war itself. Poorly managed transitions can lead to chaos, extremist resurgence, and renewed bloodshed. Well-structured ones can stabilize a nation and open a path to lasting peace.

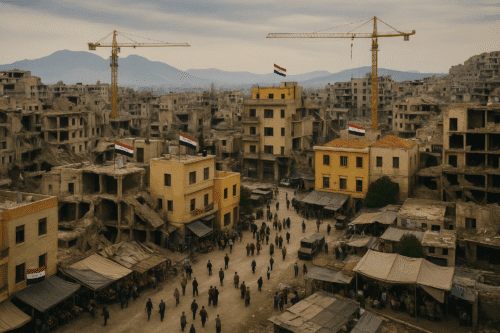

As Syria approaches a post-Assad era, it is essential to study historical precedents—both successes and failures—to avoid repeating costly mistakes. The following examples highlight where transitions have gone wrong or succeeded, each paired with a key lesson applicable to Syria today.

1. Iraq (2003–2011): The Dangers of Power Vacuums

The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 dismantled Saddam Hussein’s Ba’athist regime in a matter of weeks. What followed was a rapid and sweeping policy of de-Ba’athification, which removed thousands of civil servants, military officers, and local administrators from their positions. The intent was to break ties with the old order, but the result was an administrative collapse.

The absence of functioning institutions and inclusive governance created a vacuum. Sectarian divisions deepened as rival militias filled the gap, triggering years of violence and insurgency. By 2014, this instability paved the way for the rise of the Islamic State (ISIS).

Lesson: Transitions must preserve essential state functions while introducing reforms. Removing an entire governing class without a replacement plan can accelerate instability and empower extremist factions.

2. Libya (2011–Present): Fragmentation After Gaddafi

In 2011, NATO-backed rebels toppled Muammar Gaddafi’s four-decade rule. However, the victory quickly gave way to political fragmentation. Multiple militias, each with different loyalties and regional bases, vied for power. The absence of a unified post-Gaddafi roadmap meant no single authority could consolidate control.

Years later, Libya remains divided between rival governments in Tripoli and Benghazi. Foreign powers back different sides, further complicating efforts at national reconciliation.

Lesson: Disorganized opposition coalitions may succeed in removing a dictator but fail to govern effectively. A coordinated and inclusive transition plan is essential to prevent long-term instability and outside manipulation.

3. Lebanon (1975–1990): Sectarian Power Sharing

Lebanon’s civil war, fueled by sectarian and regional rivalries, ended with the 1989 Taif Agreement. This accord introduced a sectarian-based power-sharing system, allocating political offices by religious affiliation.

Initially, the system reduced violence and allowed for reconstruction. However, it also institutionalized divisions, making national politics hostage to sectarian bargaining. Over time, the arrangement hindered governance and perpetuated political paralysis.

Lesson: Power-sharing can be a stabilizing force in fractured societies, but if it locks communities into rigid sectarian roles, it risks entrenching divisions and obstructing reform.

4. Afghanistan (1989–2001): The Perils of Foreign Proxy Wars

After the Soviet withdrawal in 1989, Afghanistan’s various mujahideen factions—each backed by different foreign sponsors—turned on each other. Civil war followed, fueled by the agendas of regional powers like Pakistan, Iran, and Saudi Arabia.

Foreign interference prolonged the conflict and derailed attempts at national reconciliation. The chaos eventually gave rise to the Taliban, whose rule set the stage for renewed international intervention in 2001.

Lesson: Post-conflict peace efforts are easily undermined when external powers back competing factions. Diplomatic coordination among regional and global actors is crucial to avoid a descent into proxy warfare.

5. Bosnia and Herzegovina (1992–1995): The Role of Strong International Mediation

The Bosnian War’s brutal ethnic cleansing and sieges ended with the 1995 Dayton Accords. Brokered by the United States and enforced by NATO troops and UN peacekeepers, the agreement froze the conflict and established a new constitutional framework.

Though the system remains complex and often dysfunctional, Bosnia avoided a return to war. International oversight, coupled with a robust peacekeeping presence, was instrumental in maintaining stability during the transition.

Lesson: In deeply divided societies, lasting peace may require sustained international mediation, security guarantees, and a credible enforcement mechanism.

6. Yemen (2011–Present): Negotiation Without Unity

In 2011, mass protests forced President Ali Abdullah Saleh to resign after more than three decades in power. A negotiated transition installed his deputy, Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, as interim president.

The settlement failed to address Yemen’s deep political divides and excluded key actors. Within a few years, the Houthis seized the capital, sparking a full-scale civil war. Foreign interventions further entrenched the conflict.

Lesson: A negotiated settlement without genuine inclusivity or enforcement mechanisms risks unraveling. Transitional deals must integrate all major political and armed factions to be sustainable.

Relevance to Syria

The Syrian conflict is more complex than any single precedent, but the lessons above offer clear guidance.

1. Avoiding a Power Vacuum

The fall of the Assad regime will leave a delicate balance of power among opposition forces, Kurdish-led administrations, and remnants of the old state. Without a unified and representative transitional authority, extremist groups could reemerge, as seen in Iraq and Libya.

2. Managing Sectarian and Ethnic Tensions

Syria’s demographic diversity—including Alawites, Sunnis, Kurds, Druze, and Christians—requires a carefully designed power-sharing arrangement. This system must be flexible enough to foster unity while avoiding the rigid sectarian gridlock experienced in Lebanon.

3. Countering External Interference

Foreign powers such as Russia, Iran, Turkey, and the United States have entrenched interests in Syria. Without coordinated diplomacy, the post-Assad era risks becoming a new arena for proxy warfare, as happened in Afghanistan and Yemen.

4. Reconstruction and Reconciliation

Rebuilding Syria will require more than infrastructure repairs. Addressing war crimes, promoting justice, and reintegrating displaced communities will be critical for lasting peace. Failure to reconcile could perpetuate cycles of revenge and instability.

Current Media Perspectives

1. “Assad’s Opponents Are Building a New Order” – The Atlantic (December 9, 2024)

This piece outlines the fragmented but increasingly cooperative network of factions in post-Assad Syria. It highlights efforts by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) to present itself as a credible governing authority while acknowledging skepticism about its extremist past. The analysis underscores the urgent need for trust-building among Syria’s ethnic and sectarian communities.

2. “A Long Road Ahead to Decide Syria’s Future After Rapid End to Assad’s Rule” – Associated Press (December 9, 2024)

The AP focuses on Syria’s decentralized political landscape and the difficulties of creating a pluralistic government. It warns of potential sectarian violence and the challenges of integrating millions of displaced citizens into the new political order.

3. “The Times View on Syria’s New Leaders: After Assad” – The Times (December 9, 2024)

The editorial questions the intentions of HTS leader Abu Mohammad al-Julani, pointing to his al-Qaeda ties. It stresses that minority rights and inclusive governance will be crucial tests for Syria’s new rulers.

4. “After 13 Years of War, Bashar al-Assad’s Regime in Syria Has Been Defeated. What Comes Next?” – Vox (December 8, 2024)

Vox reflects on rebel promises to avoid revenge and maintain stability until a transitional government is in place. It notes U.S. concerns over the extremist backgrounds of some rebel factions and highlights the fragile security situation, especially regarding chemical weapons and Kurdish-held territories.

5. “Demise of the Butcher of Damascus Welcome, but Chaos Looms” – The Australian (December 8, 2024)

This analysis compares the current Syrian situation to the rapid Islamist advances seen in Libya and Iraq after regime collapse. It examines the roles of Turkey and Israel in shaping the emerging order.

Final Considerations for a Post-Assad Transition

Syria’s path forward will require:

- An Inclusive Transitional Authority – Representation across ethnic, sectarian, and political lines to prevent marginalization.

- Structured International Mediation – A coordinated diplomatic effort involving all major foreign stakeholders to avoid proxy conflict.

- Security Guarantees – A credible peacekeeping presence or security framework to maintain order during the transition.

- Justice and Reconciliation Initiatives – Mechanisms to address past atrocities and build intercommunal trust.

- Economic and Humanitarian Planning – Immediate focus on reconstruction, economic stabilization, and the return of displaced populations.

History shows that post-conflict transitions are fragile moments that can either open the door to peace or plunge a nation back into violence. For Syria, learning from the mistakes of Iraq, Libya, and Yemen—and adapting the successes of Bosnia—could mean the difference between a new era of stability and a repeat of the last decade’s suffering.

Leave a Reply