One of the things that sets the United States apart on the global stage is its singular independence. In much of the world, particularly across Eastern Europe, independence is a cycle. It is declared, lost, reclaimed, and redefined. Ukraine has at least three independence anniversaries. Georgia celebrates its break from the Russian Empire, the Soviet Union, and the collapse of the USSR. Even Western-aligned nations like the Philippines have multiple sovereignty dates due to colonial transitions.

But the United States has one.

July 4, 1776. One shot. One stand. One revolution that stuck.

That singularity is more than a historical accident. It reflects the unusual character of the American Revolution, a campaign not just for independence, but for self-determination. And it succeeded not through battlefield dominance or superior firepower, but through a prolonged and decentralized campaign of irregular resistance. From taverns to swamps, from coded lanterns to shattered supply lines, the American Revolution was, in essence, a sustained insurgency. A prototype for what today we would call irregular warfare.

This is not just a matter of heritage. It’s a reminder: Revolution isn’t foreign to us. It’s foundational.

The Drive for Self-Determination

What drove the American colonies to rebellion wasn’t merely taxation or the presence of British troops. It was a broader philosophical rupture. The colonists saw themselves as rightful participants in the Enlightenment, heirs to the idea that legitimacy flows upward, from people to government, not downward from monarch to subject.

The Stamp Act, the Townshend Duties, and the Coercive Acts weren’t just economic burdens. They were perceived as violations of self-governance. They catalyzed the idea that distant rule was incompatible with local liberty. To those who would eventually declare independence, the Crown’s reach into the affairs of the colonies was not merely inconvenient; it was illegitimate.

This ideological foundation gave the resistance moral clarity. It wasn’t just about British oppression; it was about reclaiming the ability to shape one’s political destiny. That clarity would give irregular actors the conviction to take enormous risks socially, politically, and militarily in defense of a new order not yet born.

Taverns, Committees, and Clandestine Networks

Before the first shots at Lexington and Concord, a resistance infrastructure had already taken root.

Taverns functioned as informal information nodes, places where news, grievances, and rumors could circulate freely. They weren’t just social hubs; they were sites of intelligence gathering, recruitment, and informal political mobilization.

Overlaying these spaces were the Committees of Correspondence, decentralized but loosely coordinated local councils that spread information and aligned resistance messaging between the colonies. They were the prototype for what we might now call an information operations cell, messaging the population while simultaneously hardening political consensus among elites.

These committees laid the groundwork for broader resistance. They built trust across colony lines, tracked Loyalist sympathizers, and circulated strategy. In modern terms, they were the civilian political wing of a hybrid insurgency, shaping both the narrative and the legitimacy of rebellion.

Coded Signals and Psychological Preparation

When Paul Revere arranged for the lanterns in the Old North Church, “one if by land, two if by sea,” he wasn’t just alerting riders. He was implementing an early activation signal, recognizable to those within a closed communication loop. It was an OPSEC-aware broadcast, deniable to outsiders but meaningful to those who knew what to look for.

This was just one of many coded systems used during the Revolution. Messages were passed orally, by courier, and in cipher. Signal fires were lit in some areas. Liberty Trees and homemade flags symbolized resistance in plain sight. These were forms of psychological preparation, meant to condition the population to resist before the first battlefield success.

Every symbolic act, from wearing a cockade to boycotting British tea, served as a form of subversion. It blurred the line between protest and rebellion, pushing neutral actors toward choosing a side and normalizing the idea of resistance.

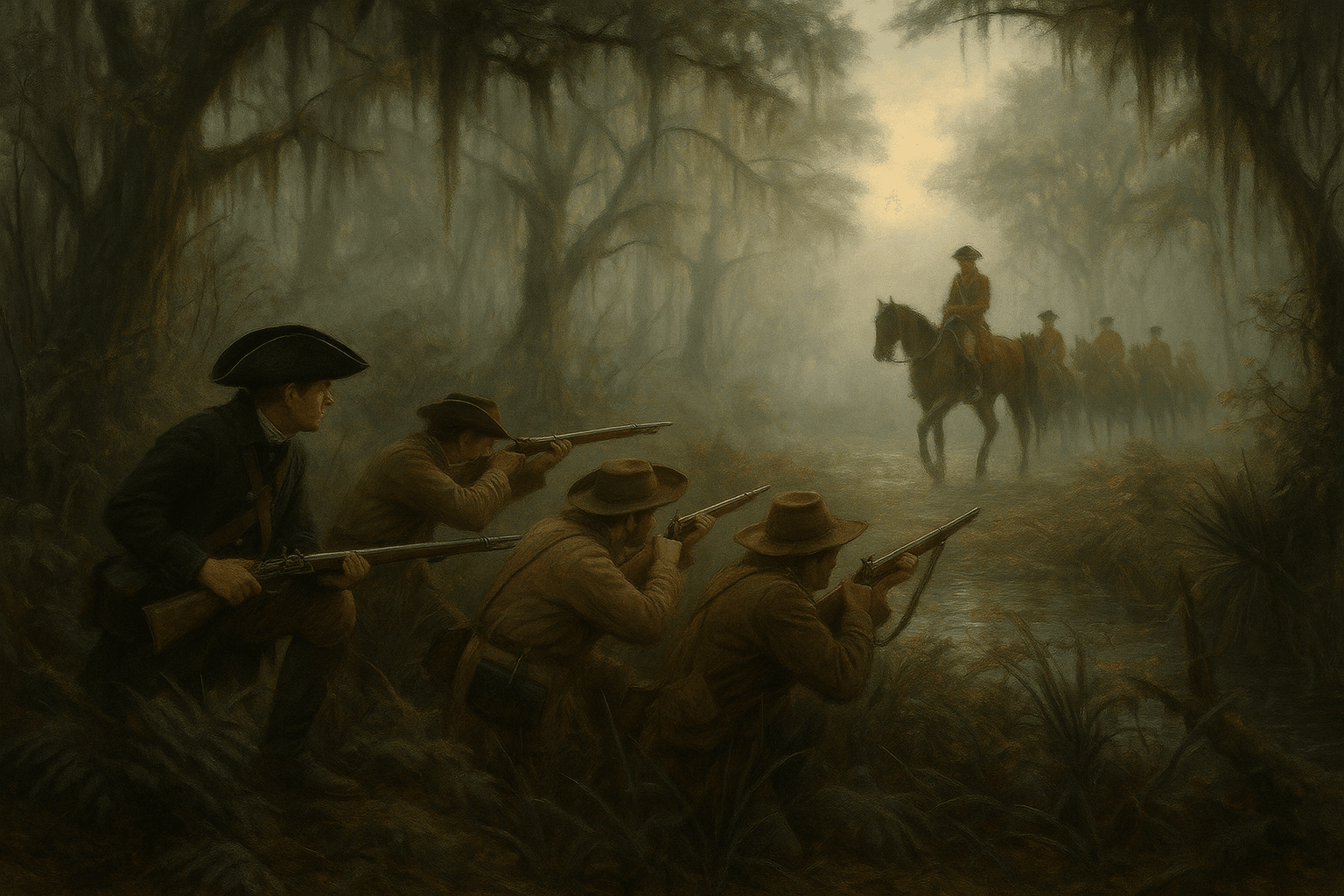

Irregular Tactics in the Field: The Swamp Fox

When fighting finally broke out, the conventional imbalance was obvious. The British Army was the most professional and best-equipped military force of its time. The Continental Army, by contrast, was fragile, poorly supplied, and frequently routed in open battle.

That’s where irregulars came in.

Few embodied this more fully than Francis Marion, known as the Swamp Fox. Operating in the lowlands of South Carolina, Marion’s forces used the terrain to their advantage, launching hit-and-run raids, ambushing supply columns, and disappearing into the marshes before organized pursuit could begin. His campaigns tied down far larger British forces, disrupted logistics, and inspired local resistance in areas the British believed pacified.

Marion’s methods were unorthodox but effective:

- No fixed base

- No standing army

- No clear frontlines

- Local knowledge, popular support, and tactical adaptability

He was not alone. Thomas Sumter, Nathanael Greene, and others employed similar tactics, creating a Southern campaign that relied on mobility, disruption, and irregular violence to exhaust the occupier.

Sabotage and Denial of Capability

The word “sabotage” was not in common use during the 18th century, but the tactics were there all the same. Patriot forces targeted British infrastructure in subtle and direct ways:

- Bridges and fords were destroyed to slow troop movement.

- Supply depots were raided or burned.

- Harbors were blocked using scuttled ships and underwater obstructions.

- Ammunition and arms shipments were stolen, intercepted, or, in some cases, adulterated.

These were not large-scale acts of destruction, but they were strategic. The goal wasn’t annihilation, it was attrition. British forces became slower, more vulnerable, and more isolated the farther they moved from their coastal bases.

The effect of sabotage was cumulative. Every delay, every missing cart, every burned bridge reinforced the message: you don’t control this terrain.

Intelligence and Diplomacy

The Revolution was also an intelligence war. George Washington understood this better than most, and his Culper Ring, a network of spies operating in British-held New York, became one of the first formal American intelligence operations.

Using codebooks, invisible ink, and dead drops, these operatives smuggled out reports on troop movements, supplies, and British intentions. The intelligence they provided helped Washington avoid encirclement, prepare ambushes, and coordinate counter-moves across multiple fronts.

Simultaneously, diplomatic insurgents like Benjamin Franklin operated abroad, especially in France, where they lobbied for arms, money, and formal recognition. Franklin’s efforts paid off in 1778 when France joined the war, turning a colonial rebellion into a transatlantic conflict and stretching British capacity to the breaking point.

It was an insurgency by every available means: military, covert, diplomatic, and psychological.

The Legacy: Irregular Roots, Enduring Impact

Understanding the American Revolution as an irregular campaign reframes how we think about national identity.

It wasn’t won by massive armies or decisive engagements alone. It was won by a distributed resistance network:

- Localized in structure

- Ideologically unified

- Operating across physical and psychological domains

- Embracing asymmetry as a strategy, not a limitation

Today, these principles echo across the world. Wherever populations resist occupation, wherever non-state actors confront great powers, the ghost of the American Revolution lingers not as a blueprint, but as a proof of concept.

And yet, the U.S. itself often forgets these roots. In modern times, we tend to see irregular warfare as something that happens “out there,” a foreign problem to be studied, countered, or contained. But the truth is simpler:

We were the insurgents once.

Revolution as Foundation, Not Exception

The American Revolution is not just a chapter in history. It is the origin story of the nation. Its tactics, networks, and ethos were irregular by nature, adaptive, decentralized, and morally grounded in the principle of self-rule.

July 4th isn’t just a date on the calendar. It’s a signal that the moment when resistance became a republic. And though we often commemorate it with fireworks, it began with whispers in taverns, scribbled notes passed in shadow, and a lantern hung in defiance.

Revolution isn’t a rupture from the American order. It’s what gave it shape.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply