Che Guevara: Revolutionary Icon, Guerrilla Strategist, and Controversial Legacy

Few figures in modern history evoke as much debate as Ernesto “Che” Guevara. His name is often linked to revolution, guerrilla warfare, and defiance against imperialism. Yet the iconic image on T-shirts and protest banners only scratches the surface. Behind the symbol was a complex strategist whose successes, failures, and unwavering ideology influenced insurgent movements across the globe.

Was Che Guevara a freedom fighter or a ruthless ideologue? Was he a brilliant tactician or an inflexible revolutionary? The truth lies between these extremes. This article examines his rise to prominence, the core principles of his guerrilla warfare doctrine, his failures in Africa and South America, and the enduring influence of his ideas on modern insurgency.

From Medical Student to Revolutionary Fighter

Guevara did not begin life as a soldier. Born into a middle-class Argentine family in 1928, he studied medicine at the University of Buenos Aires. His early worldview shifted dramatically after an extended motorcycle journey across South America in 1951–1952. Traveling through Argentina, Chile, Peru, Colombia, and Venezuela, he encountered widespread poverty, disease, and inequality.

These experiences radicalized him. Guevara concluded that systemic injustice could not be corrected through reform alone—it required armed struggle. This belief drew him to political activism and eventually into the orbit of Latin American revolutionaries.

By 1955, in Mexico City, Guevara met Fidel Castro and joined the 26th of July Movement. His medical training was valuable, but he soon proved himself as more than a field doctor. In the Cuban Revolution, Guevara served as both a commander and strategist, playing a central role in the guerrilla campaign against Fulgencio Batista’s U.S.-backed government.

The Cuban Revolution: Proving Ground for Guerrilla Warfare

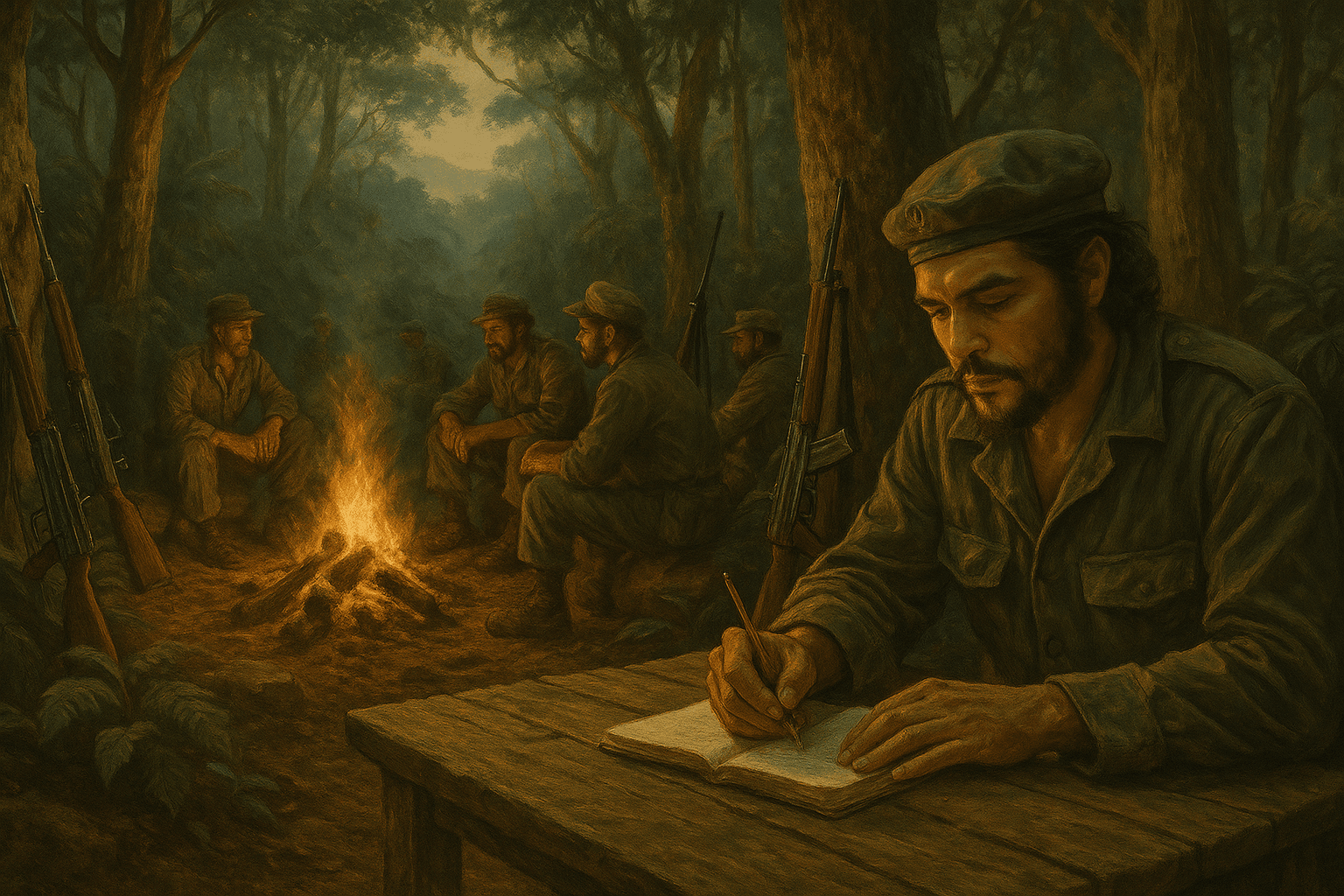

In Cuba’s Sierra Maestra mountains, Guevara developed and refined the tactics that would later define his military doctrine. Fighting alongside Castro’s forces, he commanded several successful operations against numerically superior government troops.

The rebels operated in small, mobile units. They relied on surprise attacks, ambushes, and rapid withdrawals. Rural villages provided food, recruits, and intelligence. Guevara also emphasized the political dimension of insurgency. Guerrillas offered medical care to locals, respected civilian property, and used Radio Rebelde to spread their message.

By January 1959, the Batista regime collapsed. For Guevara, the Cuban victory confirmed that a determined guerrilla force, supported by rural populations, could topple a better-equipped military.

Guevara’s Guerrilla Warfare Doctrine

Following the revolution, Guevara codified his strategies in his 1961 manual Guerrilla Warfare. His doctrine rested on three core principles:

- Small, Mobile Units – Fighters should operate in flexible groups capable of rapid strikes and retreats.

- Rural Insurgency – Revolutions begin in the countryside, where terrain and peasant support offer strategic advantages.

- Political Education – Combatants are both soldiers and educators, responsible for spreading revolutionary ideology.

In Cuba, these principles proved effective. The insurgents leveraged the mountainous terrain, limited Batista’s ability to deploy large forces, and steadily expanded their influence. They blended military operations with political outreach, turning peasant communities into allies.

However, Guevara assumed these conditions could be replicated elsewhere. This belief would later contribute to failures abroad.

The Congo Campaign: Misreading the Terrain

In 1965, Guevara sought to export revolution to Africa. He traveled to the Congo to support Marxist rebels fighting the U.S.- and Belgian-backed Congolese government. The campaign collapsed within months.

- Lack of Local Support – Congolese fighters were fragmented, poorly trained, and often indifferent to Guevara’s leadership.

- Cultural and Language Barriers – Communication breakdowns weakened coordination and trust.

- Stronger Enemy Forces – The government had external backing, better equipment, and intelligence advantages.

Guevara described the Congo mission as a “tragedy of errors.” His failure revealed that without cohesive local support and favorable terrain, guerrilla warfare could falter quickly.

Bolivia: The Final Campaign

Undeterred, Guevara turned his attention to Bolivia in 1966. He aimed to ignite a rural-based insurgency that would spread across South America. Instead, Bolivia became his last battlefield.

- Misjudging Geography – Bolivia’s terrain lacked the natural cover of Cuba’s mountains.

- Alienating the Peasantry – Locals viewed Guevara’s group as outsiders with foreign goals.

- International Intervention – The CIA and U.S. military supported Bolivian forces with training, equipment, and intelligence.

By October 1967, Bolivian troops, aided by U.S. advisors, captured Guevara. He was executed the next day in the village of La Higuera. His reported final words—“Shoot, coward, you are only going to kill a man”—cemented his image as a revolutionary martyr.

Ideological Rigidity: A Double-Edged Sword

Guevara’s commitment to Marxist-Leninist principles gave him focus and resolve. Yet his ideological rigidity often worked against him.

- Refusal to Compromise – He rejected alliances with groups whose political views diverged from his own.

- Lack of Local Adaptation – He assumed the Cuban model of insurgency could succeed anywhere, disregarding local realities.

- Alienation of Potential Allies – His uncompromising stance sometimes pushed away sympathetic movements.

Guevara envisioned revolution as a process that would create a “new man” (hombre nuevo)—selfless, disciplined, and committed to the collective good. In practice, these ideals often collided with the political and cultural complexities of other regions.

Modern Relevance of Guevara’s Strategies

Even decades after his death, Guevara’s writings influence insurgent movements worldwide. His emphasis on small-unit tactics, rural bases, and ideological training remains part of guerrilla warfare doctrine.

However, modern resistance movements face a different environment:

- Advanced Surveillance – Drones, satellites, and digital monitoring make it harder for guerrillas to hide.

- Urban-Centered Revolts – Many 21st-century uprisings begin in cities rather than remote countryside.

- Hybrid Resistance – Movements like the Zapatistas combine armed struggle with political activism and digital campaigns.

- Nonviolent Alternatives – Civil resistance has gained traction as an effective tool for political change.

While Guevara’s approach may seem dated in the age of cyber warfare, its core principles—mobility, adaptability, and political legitimacy—remain relevant.

Lessons from Success and Failure

Guevara’s career offers both inspiration and caution:

- From Cuba – The value of aligning with local populations, using terrain to advantage, and integrating political and military efforts.

- From the Congo and Bolivia – The dangers of misjudging local conditions, overestimating ideological appeal, and underestimating external opposition.

For modern strategists, Guevara’s story underscores that insurgency is context-dependent. What worked in one setting may fail in another.

Cultural Legacy and Global Symbolism

Beyond military theory, Che Guevara became a global symbol of rebellion. His image—captured in Alberto Korda’s famous photograph—has been reproduced millions of times. For some, it represents courage, sacrifice, and resistance to oppression. For others, it symbolizes violent revolution and failed ideology.

His life has inspired books, films, and academic studies. This cultural resonance ensures that debates over his legacy remain active more than 50 years after his death.

Conclusion: The Man, the Myth, the Strategic Mind

Che Guevara was more than an image. He was a doctor turned fighter, a thinker turned commander, and a revolutionary whose strategies shaped—and sometimes misled—insurgent movements worldwide.

His victories in Cuba demonstrated the potential of guerrilla warfare when matched with favorable conditions and strong local support. His failures in the Congo and Bolivia revealed the risks of applying a single model to diverse contexts. Today, his writings remain required reading for those studying unconventional warfare, even as technology and geopolitics reshape the battlefield.

Understanding Guevara is to understand the art—and limits—of revolution itself. His life and legacy remain essential for anyone examining the intersection of ideology, strategy, and the human cost of armed struggle.

Further Reading

Primary Texts by Che Guevara

- Guerrilla Warfare – Foundational work on his military strategy.

- Reminiscences of the Cuban Revolutionary War – Firsthand account of the Cuban Revolution.

- The Bolivian Diary – His final writings before capture.

Biographies and Analyses