South Korea is facing its most severe political upheaval in decades after President Yoon Suk Yeol declared martial law on December 3, 2024. Yoon said the move was necessary to counter “anti-state forces.” The National Assembly annulled the order within hours, marking a decisive moment for the country’s democracy. While the reversal showed the strength of its institutions, it also sparked mass protests, deepened political rifts, and set off a chain of legal, economic, and diplomatic consequences.

The Martial Law Declaration

In a televised speech on December 3, President Yoon accused the opposition Democratic Party (DPK), which controls the National Assembly, of “anti-state activities” and collusion with “North Korean communists.” He announced martial law effective immediately, halting the work of the legislature, suspending local assemblies, and restricting press freedoms.

It was South Korea’s first use of martial law since 1980 under military ruler Chun Doo-hwan. The decision shocked the nation and revived fears of a return to authoritarian rule. Civil society groups, opposition lawmakers, and constitutional experts condemned the decree as an abuse of presidential power.

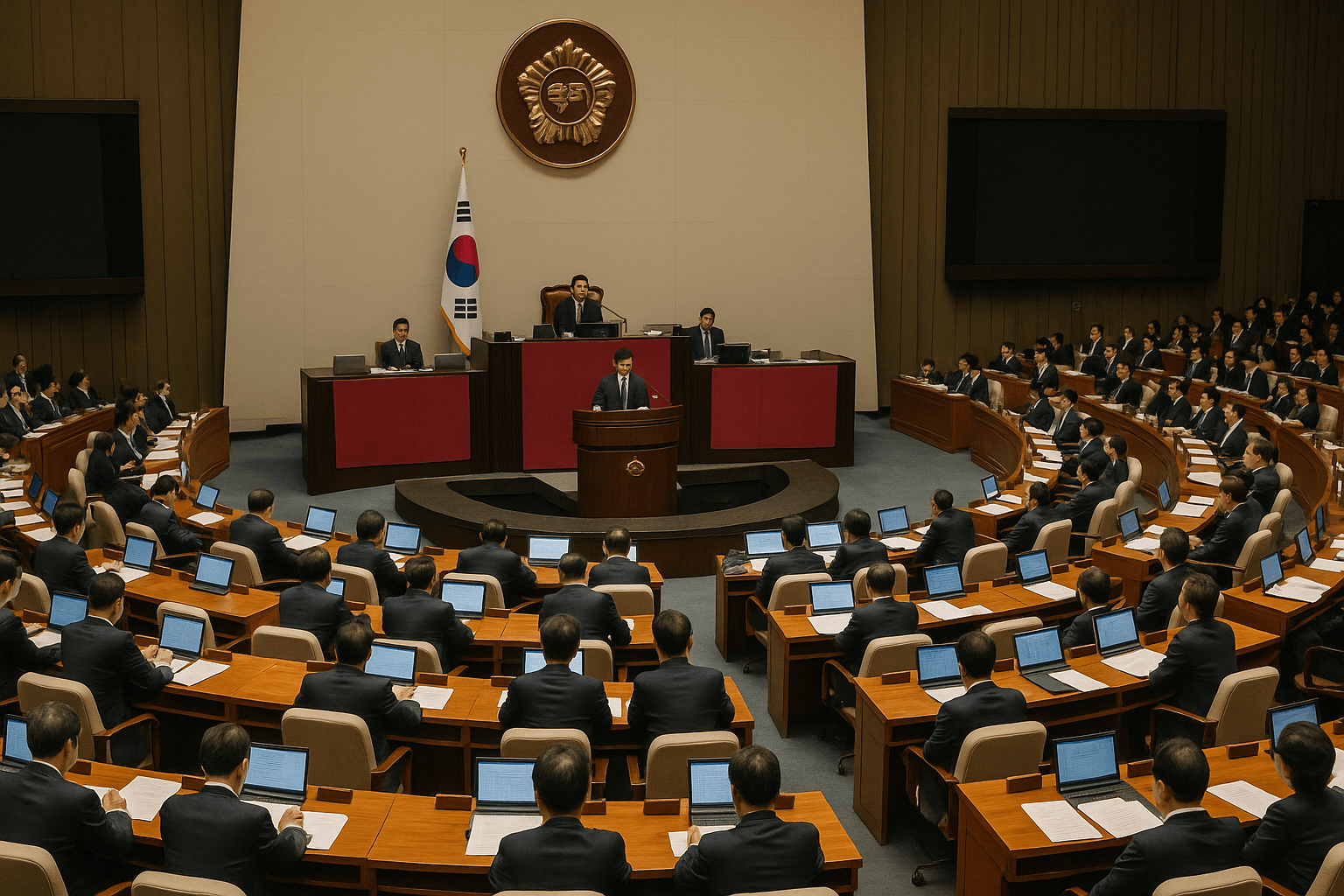

National Assembly Pushback

Despite the restrictions, lawmakers held an emergency session in the early hours of December 4. Security forces tried to block entry to the chamber, but 190 legislators succeeded in assembling. They voted unanimously to end martial law under Article 77 of the Constitution, which requires the president to comply.

Faced with unified resistance from the Assembly, Yoon rescinded the decree by around 4:00 am KST. The episode lasted less than 12 hours but set in motion a political crisis that would escalate in the days ahead.

Public Outrage and Protests

The swift reversal did not calm public anger. Thousands of protesters gathered in Seoul and other cities, many near the National Assembly building. Demonstrators included veteran pro-democracy activists and students, who warned that the move resembled the country’s past under military governments.

Protesters carried signs demanding Yoon’s resignation and chanted slogans about protecting democracy. Many drew parallels to the 1987 June Democratic Uprising, which ended decades of authoritarian rule.

Political Fallout and Impeachment

On December 14, 2024, the National Assembly voted 204–96 to impeach Yoon. Twelve members of his own People Power Party (PPP) joined the motion, exposing deep divisions in the ruling party. Yoon was suspended from office while the Constitutional Court reviews the case.

Prime Minister Han Duck-soo became acting president but lasted only two weeks. On December 27, lawmakers impeached Han for blocking special counsel investigations into Yoon and First Lady Kim Keon-hee, and for preventing the appointment of Constitutional Court judges.

The dual impeachments left Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister Choi Sang-mok serving as both acting president and prime minister—an unprecedented concentration of authority in modern South Korean politics.

Legal Consequences and Arrests

Prosecutors acted quickly against senior officials involved in the martial law attempt. Former Defense Minister Kim Yong-hyun was arrested for allegedly advising Yoon on the declaration. National Police Commissioner Cho Ji-ho and Seoul Metropolitan Police Chief Kim Bong-sik were detained on insurrection-related charges.

On December 31, the Seoul Western District Court issued an arrest warrant for Yoon—making him the first sitting president in South Korean history to face such a measure. He was detained in January 2025 on charges of leading an insurrection.

On March 7, a court revoked his detention warrant, citing procedural errors in calculating and splitting detention periods among investigative bodies. The ruling did not clear him of charges, but it opened the possibility of his release during trial.

Economic Turbulence

The crisis rattled South Korea’s economy. The won fell sharply against the U.S. dollar, prompting the Bank of Korea to keep interest rates at 3% despite weak growth. Analysts warned that political instability was dampening investor confidence and delaying corporate decisions.

The external environment also worsened. Donald Trump’s return to the White House brought renewed threats of U.S. trade tariffs on South Korean goods, particularly cars and electronics. Business leaders warned that instability in Seoul could weaken the country’s ability to respond to global trade shifts.

Strains in International Relations

The political crisis raised alarms among key allies. Officials in Washington and Tokyo stressed the need for stability in Seoul to preserve regional security. Both capitals are watching for any change in South Korea’s stance toward North Korea, China, or Russia.

Analysts warned that a shift in leadership could disrupt trilateral security coordination among the U.S., South Korea, and Japan—potentially weakening deterrence strategies in the Indo-Pacific.

Democratic Resilience Under Pressure

Even amid the turmoil, the crisis showed the resilience of South Korea’s democracy. The National Assembly exercised its constitutional power to end martial law within hours. Citizens mobilized quickly to defend democratic norms through peaceful protest.

The judiciary demonstrated independence by pursuing legal cases against senior officials, including the president. These actions sent a clear signal that no leader is beyond the reach of the law.

Still, the episode revealed weaknesses. The executive’s ability to bypass safeguards so abruptly points to a need for stronger institutional checks. Growing political polarization could also erode public trust if leaders fail to bridge divides.

Looking Ahead

The Constitutional Court’s ruling on Yoon’s impeachment will shape the next stage of the crisis. A decision to remove him permanently could reset the political landscape. Ongoing trials of senior officials will test the independence of the judiciary.

To restore confidence at home and abroad, the next leadership must commit to transparency, legal reform, and cross-party dialogue. Stabilizing the economy will be essential to reassure markets and investors. On foreign policy, consistency in security cooperation will be critical to maintaining deterrence in a volatile region.

Conclusion

President Yoon Suk Yeol’s December 2024 declaration of martial law and its rapid reversal have plunged South Korea into uncharted territory. The fallout has included two impeachments, the arrest of senior officials, and ongoing legal battles.

The crisis has exposed vulnerabilities in executive oversight but also confirmed the strength of South Korea’s institutions and civil society. The coming months will determine whether this resilience can be sustained and whether leaders can restore political stability without compromising democratic values.

How South Korea navigates this moment will define its domestic future and its role in the regional and global order. The stakes could not be higher—for its democracy, its economy, and its alliances. This test will shape not only its domestic future, but also its role in the regional and global order.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply