In the darkness of the eastern Pacific, a floating city of light drifts beyond Ecuador’s territorial waters. Hundreds of Chinese fishing vessels illuminate the horizon, their floodlights cutting through the night while satellite transponders flicker off one by one. To the untrained eye, this looks like ordinary commerce. To regional navies and maritime analysts, it signals something deeper, a new front in global competition where extraction and strategy merge.

China’s distant-water fishing fleet is the largest in the world, operating from the Galápagos to West Africa. Behind its immense scale lies a system of subsidies, dual-use design, and state coordination that transforms fishing into an instrument of economic warfare. This approach fuses commercial enterprise with paramilitary capability. It allows Beijing to project influence, harvest resources, and erode competitors’ maritime resilience without firing a shot.

The result is a slow-motion struggle for control of the global commons. Fish stocks vanish, enforcement agencies are outnumbered, and coastal economies grow dependent on foreign vessels that act as both predator and proxy. Understanding this pattern is critical to grasping how China wields non-kinetic power across the world’s oceans, not as an accident of commerce, but as a deliberate extension of state strategy.

Theoretical Foundations

China’s maritime strategy thrives in the spaces between peace and war. This realm, often called the grey zone, allows the state to advance interests incrementally while avoiding the thresholds that trigger conventional military responses. The fishing fleet fits seamlessly into this design. They occupy disputed reefs, shadow rival patrols, and report on foreign activity under the cover of ordinary work. The same logic that governs cyber intrusions and disinformation campaigns applies here: saturate the environment until the target normalizes encroachment.

Economic and Resource Warfare

Resource warfare theory describes competition for strategic commodities as a form of non-kinetic conflict. China’s distant-water fleet embodies this logic on the world’s oceans. Having exhausted many domestic fish stocks, Beijing’s planners treat distant fisheries as an extension of national food security and economic sovereignty. Subsidized fuel, tax exemptions, and direct construction incentives make it possible to operate where ordinary market forces would fail. The fleet’s reach now extends from the South Pacific to the Gulf of Guinea. This expansion secures low-cost protein for the domestic market while undermining the resource bases of weaker coastal economies.

Hybrid Militia Doctrine

Under People’s War at Sea, provincial districts can mobilize parts of the fleet as maritime militia for surveillance, blocking, and swarming in disputed waters. These maritime militia units are often described as “the third sea force” alongside the navy and coast guard. They extend state presence under the guise of private labor. When deployed near contested reefs or foreign EEZs, they can block, swarm, or shadow other vessels without triggering armed confrontation. The distinction between commerce and coercion becomes blurred, which is the strategic point. By operating in this legal and tactical ambiguity, the fleet functions as an inexpensive extension of military power, a paramilitary network that can be mobilized faster than a warship and justified as economic activity.

Game-Theoretic Pressure and Capacity Advantage

Game theory helps explain why this system is effective. In a maritime environment where enforcement is costly, the actor with greater capacity and lower operating costs can dominate through persistence. China’s subsidies reduce marginal costs and allow fleets to overwhelm local enforcement through sheer presence. Each incursion imposes a response cost on the target state, forcing a losing equation: one patrol boat cannot challenge a hundred subsidized trawlers. Over time, the smaller state rationalizes nonresponse, creating de facto acceptance of Chinese activity.

Precedent for Paramilitary Fishing

Fishing as sovereignty assertion is not new, but China’s implementation is unprecedented in scale and integration. Historical examples from the Soviet distant-water fleets and later Russian Arctic operations show similar dual-use functions: surveillance, logistics, and flag presence. Yet those were peripheral to state power projection. In China’s case, the fleet forms a deliberate layer of coercive capability built into national maritime planning. This structural linkage, between militia doctrine, resource extraction, and global logistics, distinguishes it as a tool of statecraft rather than a byproduct of commerce.

Paramilitary Fishing-Force Model

Subsidy and Capacity Engine

At the foundation of China’s distant-water fleet lies a vast subsidy structure that transforms fishing into a strategic enterprise. Fuel rebates, vessel construction incentives, and tax exemptions allow companies to operate at distances that would be uneconomical under normal market conditions. Government data reviewed by independent researchers shows that China has consistently ranked as one of the world’s largest providers of harmful fishing subsidies, totaling billions of dollars annually. These payments sustain overcapacity and keep the fleet active even as profit margins shrink.

Dual-Use Vessel Doctrine

China’s distant-water vessels are not identical to their commercial counterparts. Many have reinforced hulls, high-bandwidth communication suites, and extended storage capacity. These upgrades are consistent with both fishing endurance and paramilitary mobilization. Provincial governments designate certain trawlers as “backbone vessels,” a classification that carries eligibility for additional subsidies and militia coordination. These fleets participate in exercises alongside maritime law-enforcement ships and are tasked to relay surveillance data to coastal command networks. The blurred identity of these vessels complicates international response, since enforcement actions risk escalation while inaction normalizes their presence.

Opacity as Operational Method

Fleets frequently disable Automatic Identification System transponders, manipulates vessel identities, or re-flag under foreign registries to conceal ownership. These “dark fleets” operate beyond immediate monitoring and exploit gaps in maritime governance. Ship-to-ship transshipment further obscures the origin of the catch, allowing products to enter legitimate supply chains. Analysts using VIIRS night-light data have identified large concentrations of Chinese squid jiggers operating invisibly within prohibited zones, including North Korean waters under United Nations sanctions. This behavior illustrates how deliberate opacity functions as a shield for state objectives, enabling resource extraction and strategic positioning without clear attribution.

Logistics, Basing, and Sustainment

Sustaining such far-reaching operations requires a logistical infrastructure akin to a naval network. China has established a series of overseas fishing bases, repair docks, and refrigerated cargo transshipment points stretching from Hainan to Mauritania. This network extends the fleet’s endurance and forms the maritime equivalent of expeditionary sustainment. Some of these facilities overlap with ports used for Belt and Road Initiative projects, blending commercial investment with strategic access. The Office of Naval Intelligence has noted that distant-water fishing vessels benefit from navy and coast guard support in contested areas, including refueling and emergency cover. This overlap further erodes the line between commercial and state assets, embedding the fishing fleet within China’s broader system of maritime power projection.

Strategic Intent Embedded in Policy

Official Chinese documents link the expansion of the distant-water fleet directly to national development goals. The 13th and 14th Five-Year Plans refer to fisheries as part of maritime resource modernization and food-security assurance. The China Fisheries Yearbook lists foreign fishing bases as “strategic nodes” for national interest. This language indicates intent beyond simple economic opportunity. It reflects a worldview where the ocean is a domain of comprehensive national power, measured not only by naval strength but by the ability to sustain, occupy, and profit from it.

Operational Patterns and Precedents

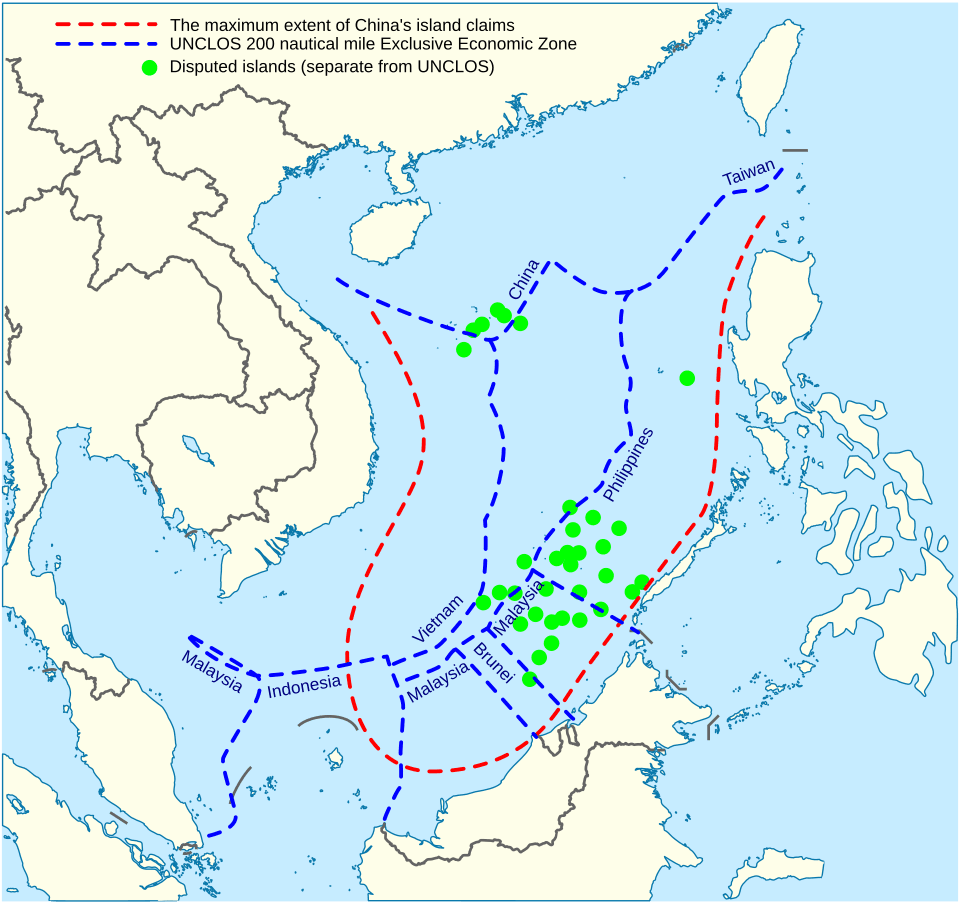

The South China Sea: The Prototype

The South China Sea serves as the laboratory for China’s hybrid maritime strategy. Here, fishing vessels operate in concert with coast guard and naval units under a system often referred to as the “cabbage tactic.” Layers of fishing boats surround disputed features, backed by heavier law-enforcement and naval vessels at distance. The effect is constant occupation without overt conflict. Satellite data from the U.S. Naval War College and the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative have verified dozens of mass anchorages at Whitsun Reef, Mischief Reef, and Subi Reef, many lasting for months with no evidence of fishing. The pattern suggests intent to hold and normalize presence rather than to harvest resources.

Galápagos and the Latin American Periphery

In July 2020, Ecuador’s navy tracked a fleet of nearly 300 Chinese fishing vessels congregating just outside its exclusive economic zone near the Galápagos Islands. Many vessels switched off their AIS transponders, while others conducted ship-to-ship transfers with refrigerated cargo ships. The fleet targeted squid and other high-value species, threatening one of the most biodiverse marine regions in the world. Ecuador’s naval chief publicly accused the fleet of ecological predation and warned of incursions into protected waters. Similar patterns have since appeared along the coasts of Peru, Argentina, and Chile, all showing the same logistical sophistication: extended deployments, reflagging, and minimal transparency.

West African Waters: Economic Pressure Zone

West Africa’s coastal states have become some of the most heavily exploited fishing grounds on earth. Chinese distant-water vessels now account for a dominant share of industrial fishing effort in the Gulf of Guinea and along the coasts of Senegal and Ghana. Local enforcement agencies, often operating with only a handful of patrol boats, struggle to track or interdict large foreign fleets. According to the Overseas Development Institute, illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing in this region costs coastal economies between two and nine billion dollars annually. The depletion of local stocks displaces artisanal fishers, fuels food insecurity, and deepens dependency on imported seafood, often from Chinese suppliers.

The Polar Edge: New Frontiers

Recent tracking data indicates Chinese vessels are increasingly active in polar regions, particularly in the Southern Ocean near Antarctica. These expeditions target krill and toothfish, both critical components of marine food webs. The presence of distant-water fleets so far from home aligns with China’s declared goal of becoming a “polar great power.” Official policy papers refer to polar fishing as part of “blue economy development” and “global ocean governance participation.” While no militia integration has been confirmed in these fleets, the pattern, state-backed, subsidy-supported, and strategically placed, mirrors the same operating logic.

Case Study: Argentina’s Enforcement Dilemma

In 2016, the Argentine Coast Guard sank a Chinese trawler, the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 010, after it allegedly attempted to ram a patrol vessel during pursuit for illegal fishing. The incident underscored both the brazenness of distant-water fleets and the risk of escalation when states attempt enforcement. China protested diplomatically and demanded accountability, illustrating how paramilitary logic shields its fleets through legal ambiguity. For Argentina and similar nations, each enforcement action invites political and economic repercussions. The event became a cautionary example for weaker states that lack leverage to manage post-incident fallout.

Patterns Across Theaters

Across every oceanic region, common traits emerge: massed deployments, operational opacity, political shielding, and rapid adaptation to local enforcement gaps. Each fleet behaves according to local conditions but follows a consistent doctrine rooted in state sponsorship and economic warfare. The fleet’s ability to sustain operations simultaneously in multiple regions demonstrates the maturity of the logistics network and the global scalability. Understanding these operational precedents is the first step toward countering them at scale.

Comparative Scale and Precedent

The hidden war at sea: China’s illegal fishing explained

YouTube · Uploaded April 2, 2025

The Scale of Global Dominance

China’s distant-water fishing fleet is unparalleled in size and reach. From 2022 through 2024, open-source data compiled by Global Fishing Watch showed Chinese-flagged vessels responsible for roughly 44 percent of all visible industrial fishing effort worldwide, and about 30 percent of all high-seas operations. This presence is not evenly distributed, it dominates every major tuna, squid, and pelagic fishery from the central Pacific to West Africa. The scale alone creates strategic leverage: in regions where one actor controls the majority of extraction, resource availability becomes a political tool. China’s capacity advantage allows it to exhaust local stocks while offering replacement imports through state-linked seafood conglomerates, converting ecological imbalance into economic dependency.

A Peer Group Without Parity

Other major distant-water fishing nations, Spain, Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea, also maintain global operations but with fundamentally different structures. Their fleets are primarily corporate, commercially financed, and constrained by regional fisheries agreements. Enforcement incidents involving these fleets are comparatively limited, and state coordination is largely regulatory rather than operational. In contrast, Chinese vessels receive direct state subsidies, militia coordination, and foreign basing support. This asymmetry produces both economic and strategic imbalance, where industrial presence doubles as geopolitical signaling. The gap is quantitative and doctrinal, China operates a global militia-commercial hybrid, while others manage commercial fleets under international governance norms.

Soviet and Russian Precedents

There are historical analogs, though none at current scale. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union maintained a global fishing fleet that doubled as an intelligence and logistics network. Trawlers carried communications intercept equipment, monitored Western naval activity, and provided covert sustainment for Soviet submarines and research ships. Post-Soviet Russia retained fragments of this infrastructure, particularly in Arctic operations tied to Northern Sea Route development. Yet those fleets were extensions of state secrecy, not a normalized economic instrument. The Chinese model differs by embedding strategic purpose into commercial viability.

The Belt and Road Connection

China’s maritime expansion is also fused to its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Port investments in Gwadar (Pakistan), Walvis Bay (Namibia), Nouadhibou (Mauritania), and Paita (Peru) serve dual functions: commercial infrastructure and logistical sustainment for fishing fleets. Official Chinese sources describe these as “maritime cooperation nodes,” but patterns of use show overlap with distant-water fleet servicing. By anchoring fleet logistics to BRI ports, China effectively globalizes its maritime militia footprint without overt military basing. This alignment of economic policy and security architecture makes the fishing fleet both a beneficiary and an instrument of BRI’s expansion, embedding strategic presence within development partnerships that appear civilian in nature.

Implications of Scale

The unprecedented breadth of China’s distant-water presence establishes a structural imbalance in global maritime governance. No other state or consortium possesses the enforcement reach or political cohesion to regulate activity at this magnitude. The result is a de facto monopoly over portions of the global commons, sustained by state subsidy and shielded by legal ambiguity. Where warships would signal confrontation, trawlers achieve the same effect invisibly, day after day, under the pretext of trade.

Resource Extraction as Strategy

China’s fishing fleets are often described as overzealous exporters or undisciplined profit seekers. Yet when analyzed through the lens of national strategy, their behavior aligns closely with the doctrine of economic warfare, the use of financial and resource instruments to weaken competitors and enhance national strength. Beijing’s planners view fisheries as part of comprehensive security, connecting protein supply, employment, and maritime sovereignty. As domestic fish stocks collapsed under decades of exploitation, the state turned outward.

From Food Security to Power Projection

Food security provides political justification for distant-water expansion, but its implementation far exceeds subsistence needs. Chinese official documents and speeches portray fishing as an extension of the Belt and Road Initiative, serving both economic and diplomatic ends. By ensuring access to seafood imports for domestic consumption, China simultaneously builds influence over nations dependent on fishing licenses and seafood trade. This duality mirrors other elements of its global strategy, where infrastructure, credit, and resource access blend into one system of leverage. Fisheries thus become a diplomatic currency: China offers market access and joint ventures while ensuring its own fleets dominate extraction. Over time, this arrangement transforms dependency into quiet compliance.

Attrition Through Economics

Economic warfare does not require open conflict; it functions through exhaustion. Coastal states with limited maritime enforcement capability cannot afford continuous patrols, and their economies cannot withstand prolonged depletion of fish stocks. When Chinese fleets appear, local industries face an impossible choice: attempt enforcement and risk diplomatic fallout, or ignore violations and face economic collapse. Both outcomes benefit Beijing. The first demonstrates regional dominance; the second ensures continued access. This dynamic exemplifies economic attrition, inflicting unsustainable costs on opponents without overt aggression.

Lawfare and Political Shielding

Legal ambiguity is a central feature of this strategy. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) grants states jurisdiction over their exclusive economic zones but provides limited enforcement capacity against foreign incursions. China exploits these gaps, insisting that its fleets operate lawfully while portraying foreign objections as political hostility. When incidents occur, such as collisions or arrests, Beijing deploys diplomatic protests, economic incentives, or sanctions to deter future challenges. This practice, known as lawfare, transforms international legal frameworks into defensive armor for state-sponsored activities. Fishing vessels become proxies for legal testing: they probe jurisdictional boundaries and shape interpretations favorable to China’s long-term maritime claims.

Integration with Maritime Governance

Beijing’s approach to global fisheries management further reinforces this posture. China participates actively in regional fisheries organizations, often lobbying to expand allowable catch quotas or block conservation measures that might restrict its fleet. At the same time, it provides aid and infrastructure loans to the very nations whose waters it exploits, framing itself as a partner in “capacity building.” This dual strategy co-opts regulatory bodies and constrains diplomatic opposition. It mirrors patterns observed in other sectors of Chinese influence operations: integrate into the system, then steer it from within.

The Deterrence Value of Civilian Presence

Deterrence at sea has traditionally relied on visible naval power, but China’s fleet achieves a subtler effect. Thousands of civilian vessels operating persistently in contested waters create a form of deterrence through normalization. Any attempt to challenge them risks escalation, while inaction concedes presence. The cost-benefit ratio favors China: commercial vessels are cheap, replaceable, and politically deniable, yet collectively they occupy territory and signal resolve. This mass of civilian activity substitutes for hard military confrontation. In essence, fishing fleets function as a distributed, low-cost force that continuously tests and erodes rival claims. The deterrence achieved through this constant presence is psychological and political rather than kinetic.

The Global Economic Feedback Loop

As Chinese fleets expand, global seafood markets increasingly depend on their output. This dependency creates leverage over import-dependent nations, particularly in Asia and Africa. By controlling both supply and pricing, Beijing can influence domestic markets abroad, a nonmilitary mechanism of coercion. The result is a self-reinforcing cycle: resource extraction abroad strengthens China’s domestic market and industrial base, which in turn finances further expansion. Every ton of fish pulled from foreign waters becomes both an economic asset and a strategic signal, a demonstration of the state’s ability to dominate shared resources under the pretense of open commerce.

International Law’s Structural Gaps

The international legal framework governing the oceans was never designed for hybrid actors. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) defines clear categories, naval, commercial, and civilian, but the Chinese fishing fleet operates in the spaces between. These vessels are neither private in the full market sense nor state-owned in the traditional way. When challenged, Beijing invokes UNCLOS provisions protecting freedom of navigation and the right to fish on the high seas. Yet when its vessels are intercepted, the state asserts diplomatic immunity through consular channels. This dual posture allows China to weaponize ambiguity: its fleet benefits from the protections of commerce and the privileges of sovereignty simultaneously. Enforcement agencies in smaller states, aware of their legal and political vulnerability, often refrain from confrontation.

Weak Enforcement and the Problem of Attribution

Attribution remains the most persistent obstacle to legal accountability. Many Chinese-flagged vessels are owned by shell companies or re-registered under flags of convenience in countries such as Panama or Belize. Ownership structures are opaque, designed to distance the Chinese state from operational liability. Even when satellite evidence proves illegal activity, prosecutions falter because jurisdiction is unclear. Ship-to-ship transshipment compounds the difficulty by mixing catches from multiple sources, erasing traceability. This legal fog undermines both national and international enforcement, transforming regulation into a paper exercise. For every vessel detained, hundreds continue operations unchecked, demonstrating that deterrence through prosecution is ineffective against a system engineered for plausible deniability.

Lawfare as Defense

Beijing’s approach to maritime disputes demonstrates a sophisticated understanding of international law as both shield and sword. Through diplomatic protests, domestic legislation, and participation in global bodies, China constructs an appearance of legal conformity even as it erodes practical enforcement. The creation of large fishing “associations” and “cooperatives” provides collective cover, allowing the state to claim that actions are purely private while retaining control through subsidies and tasking. In disputes such as the South China Sea arbitration, China rejected adverse rulings while emphasizing its compliance with general maritime law, an inversion that turns international norms into instruments of narrative control. This practice exemplifies lawfare, where adherence to the form of legality conceals violation of its substance.

Limitations of Multilateral Mechanisms

Regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) and the Port State Measures Agreement were established to combat illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing. In practice, they rely on voluntary compliance and limited enforcement capacity. China participates actively in many of these bodies, but its voting power and economic influence enable it to dilute or delay restrictive measures. Port inspection regimes remain inconsistent, particularly in developing countries dependent on Chinese investment. Even when vessels are blacklisted, loopholes allow re-registration under new names. The same diplomatic leverage that sustains Belt and Road infrastructure projects operates within these multilateral settings, where financial dependency discourages confrontation. The result is a global regulatory system that China can navigate more effectively than any of its rivals.

Trade Regulation and Supply-Chain Vulnerabilities

Efforts to curb illegal fishing increasingly depend on trade transparency. The United States Seafood Import Monitoring Program and the European Union Catch Certification Scheme require documentation of harvest origin and vessel identity. Yet both systems face evasion through falsified paperwork and transshipment at sea. When cargo changes hands multiple times before reaching port, traceability collapses. Chinese fleets exploit these weaknesses by landing catches through intermediary states that lack verification infrastructure. Because seafood markets are global, even strict domestic import laws cannot isolate illicit product streams. The legal framework of trade thus mirrors the maritime one: robust on paper, porous in practice.

The Enforcement Dilemma for Coastal States

For coastal nations in Africa, Latin America, and the Pacific Islands, confronting Chinese fleets presents a strategic dilemma. Enforcing their rights risks economic retaliation, while inaction invites resource collapse. China’s foreign ministry often frames enforcement as “unfriendly acts” or “misunderstandings,” placing weaker states in political isolation. Joint patrol initiatives with the United States, Japan, or Australia offer partial relief but expose local governments to diplomatic pressure from Beijing. This tension reveals the deeper structural issue: international law assumes good-faith participation, yet China’s model leverages ambiguity as a competitive advantage. Until the global community recognizes that legal instruments can be exploited as strategic weapons, enforcement will remain reactive and piecemeal.

What Can Be Done

The Need for Layered Deterrence

China’s distant-water fishing operations exploit every weakness in maritime governance: jurisdictional gaps, enforcement limits, and legal ambiguity. A single-solution response will fail. What is required is layered deterrence, combining technology, diplomacy, and economic leverage. Enforcement must become both horizontal and vertical, horizontal across nations sharing intelligence, and vertical across civil, military, and economic agencies within states. Without integration, isolated efforts simply displace illegal activity from one region to another.

Maritime Domain Awareness as the First Line

Visibility is the foundation of deterrence. The ability to monitor fleets in near-real time transforms enforcement from reactive to predictive. New systems that fuse satellite imagery, radar, and optical sensors now make it possible to detect “dark fleets” even when vessels disable their transponders. Programs such as SeaVision, developed by the U.S. Navy and shared with partner nations, allow allies to visualize activity across vast ocean regions. For smaller coastal states, pooled satellite subscriptions and shared analytics centers can deliver this capability at sustainable cost. When information is shared multilaterally, opacity loses value.

Joint Enforcement and Shiprider Programs

Regional cooperation multiplies limited enforcement capacity. The Shiprider Program used in the Pacific Islands allows officers from one state to ride aboard another’s patrol vessels, extending jurisdiction and closing legal loopholes. This model has proven effective in the North Pacific Guard and could expand to Africa’s Gulf of Guinea or Latin America’s Pacific coast. When paired with automatic evidence collection, video, GPS, and catch-log transmission, joint patrols turn into mobile legal instruments. The goal is not confrontation but credible enforcement: to demonstrate that distance and numbers no longer guarantee immunity.

Economic Pressure Through Market Transparency

Because most seafood enters global trade networks, economic tools may prove more decisive than patrol boats. Expanding import traceability, standardizing electronic catch documentation, and mandating public vessel registries could cut off markets for illegal product. The United States, the European Union, and Japan together account for more than half of global seafood imports. A unified compliance regime among these markets would make it difficult for illicit Chinese catches to find legal buyers. Corporations controlling processing and retail supply chains must be compelled to audit origin data and disclose high-risk suppliers. Market denial transforms resource warfare into a financial liability.

Reforming Subsidies and Incentives

The World Trade Organization Agreement on Fisheries Subsidies, which entered into force in 2023, prohibits funding for vessels engaged in illegal or unreported fishing. Full implementation, coupled with independent verification, could strip the economic foundation from distant-water overcapacity. Major economies should pressure China to disclose its subsidy ledger under WTO transparency obligations. Simultaneously, alternative incentive models can reward sustainable fishing practices among developing coastal states. Redirecting funds from harmful subsidies to conservation creates both political legitimacy and practical deterrence.

Building Legal Clarity and Accountability

Legal reform must focus on attribution. Every vessel engaged in industrial fishing should have a single, immutable identity code linked to beneficial ownership. Multilateral databases, accessible to coast guards, customs agencies, and prosecutors, can close the anonymity loophole. Legal scholars have proposed classifying repeat violators as state-linked commercial auxiliaries, which would remove civilian protections and open the door to sanctions. The concept mirrors counter-terror finance models, where pattern analysis determines culpability.

Diplomatic Coordination and Strategic Signaling

Diplomatic deterrence requires unity of message. When individual nations protest Chinese incursions, Beijing isolates and pressures them economically. Collective statements through regional forums such as ASEAN, the African Union, and the Pacific Islands Forum distribute risk and increase legitimacy. Coordinated demarches backed by intelligence evidence force China to expend diplomatic capital defending its fleet rather than setting the narrative. Simultaneously, public diplomacy, publishing high-resolution imagery of illegal activity, denies Beijing control of perception.

Technological Innovation and Non-Kinetic Countermeasures

Emerging technologies can neutralize the scale advantage of large fleets. Small autonomous surface drones equipped with cameras and AIS sniffers can patrol vast areas at a fraction of traditional cost. Machine-learning algorithms trained on vessel behavior can flag anomalies within hours, allowing enforcement to act on precision rather than probability. Even low-cost measures, like satellite-enabled distress buoys distributed to artisanal fishers, create citizen sensors that feed into shared intelligence networks.

Strategic Messaging: From Compliance to Consequence

The final layer of deterrence is psychological. China’s distant-water captains act boldly because consequences are rare. Enforcement agencies must shift from compliance rhetoric to consequence certainty. This includes public vessel blacklists, asset seizures in foreign ports, and targeted sanctions against corporate directors linked to repeated violations. Equally important is rewarding positive behavior, granting trade preferences to fleets with verified sustainable practices. The goal is cultural: make illegal fishing an act of strategic liability rather than national service.

Layered deterrence is achievable. It requires coordination equal to the scale of the problem and the recognition that what appears commercial can be coercive. Every action that makes the invisible visible, through data, law, and diplomacy, reclaims space from coercion and reasserts the rule of law at sea.

Evaluating Evidence and Inference

Understanding China’s grey zone activity requires distinguishing what is known through verified data from what is assessed through behavioral inference and strategic pattern analysis. This approach anchors conclusions in transparent reasoning, ensuring that analytical judgment never drifts into speculation.

| Dimension | Known (verified through data or documentation) | Assessed (supported by pattern and inference) |

|---|---|---|

| Fleet Size and Reach | China operates the world’s largest distant-water fleet, responsible for approximately 44 percent of visible global fishing effort. Satellite data confirms presence across all major ocean regions. | The full operational footprint, including “dark fleets” operating with AIS disabled, is likely significantly larger than reported, extending beyond documented zones. |

| State Subsidies | Central and provincial governments provide billions in annual fuel and vessel subsidies, verified through Chinese budget documents and WTO reports. | Subsidies are used strategically to maintain geopolitical presence rather than purely economic viability, converting inefficiency into influence. |

| Maritime Militia Integration | Official Chinese sources and Western defense studies confirm militia units under provincial defense control, operating in the South China Sea. | The same integration is likely replicated in distant-water fleets globally through informal coordination and communications networks. |

| Operational Opacity | Global Fishing Watch and FAO data confirm widespread AIS darkening and transshipment practices tied to Chinese fleets. | The pattern of opacity is deliberate, designed to conceal state coordination rather than evade incidental regulation. |

| Economic Impact on Coastal States | ODI and World Bank studies show billions in annual losses to African and Latin American fisheries linked to IUU activity by Chinese vessels. | These losses are exploited as a coercive mechanism, fostering economic dependency and diplomatic silence. |

| Legal Positioning | China leverages UNCLOS protections while rejecting rulings unfavorable to its maritime claims. | This dual legal posture forms part of a broader lawfare campaign that transforms international law into a strategic shield. |

| Fleet as Deterrence | Persistent deployments around contested reefs are verified through satellite imagery. | The behavior constitutes an intentional deterrent mechanism—civilian presence as a substitute for overt military confrontation. |

Interpretive Summary

The weight of evidence indicates that China’s distant-water fishing program is neither accidental nor purely commercial. Verified data shows scale, coordination, and state support beyond any other fleet. What is assessed, but supported by consistent behavior, is the strategic intent to use that fleet as an instrument of economic and resource warfare. Distinguishing these categories is essential: it prevents alarmism while revealing a pattern of deliberate statecraft that thrives in ambiguity.

Logic and Limits

China’s distant-water fishing fleet is not simply commercial. It fuses subsidies, logistics, militia doctrine, and legal ambiguity into a durable instrument of state power. Verified data show Chinese vessels conduct the largest share of industrial fishing and dominate high-seas activity. This scale distorts local economies, weakens conservation, and normalizes encroachment around contested waters. When fleets can mass, darken transponders, and feed opaque supply chains, governance erodes and dependency deepens, control achieved without conquest.

Countering this system requires layered deterrence. Transparency technology can expose dark operations, while trade measures can raise the cost of illicit product. WTO rules on harmful fisheries subsidies provide leverage when paired with vessel blacklists and public evidence. Linking market access to traceable, verifiable catch shifts financial risk back to coordinated fleets and their sponsors.

Practical defense begins with shared maritime-domain awareness, joint shiprider patrols, and rigorous port-state controls that block suspect vessels. Harmonized import monitoring and mandatory ownership disclosure connect detection to sanction. These steps civilize enforcement rather than militarize it, narrowing the gap between what is observed and what can be prosecuted.

Chinese fishing operations demonstrate how a state can weaponize routine commerce. The global response must make enforcement equally routine, law, markets, and sensors aligned so that presence without accountability ceases to be a rational strategy.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply