Sabotage—the deliberate destruction or disruption of resources, operations, or systems—has long been a vital tactic in warfare. Often wielded by smaller forces unable to confront enemies directly, it allows them to erode the power and momentum of larger, better-equipped adversaries. From the physical destruction of ancient siege engines to the precision of modern cyberattacks, sabotage has continuously adapted to the technologies and vulnerabilities of its era. Yet its core objective remains the same: to undermine the enemy’s ability to fight, supply, or govern effectively.

Origin of the Term-Sabotage

The word sabotage originates from the French word sabot, meaning a wooden shoe or clog. In the early 19th century, saboter meant “to walk noisily” or “to clumsily interfere,” but the term took on more subversive connotations during periods of industrial unrest. A common—though likely apocryphal—origin story suggests that disgruntled French workers threw their wooden shoes into machinery to damage equipment during labor disputes. While this specific tale is debated among historians, the word sabotage began to be widely used in the early 20th century to describe deliberate acts of destruction or disruption, particularly in the context of labor resistance and later, warfare. The term has since evolved to encompass a broad range of covert or clandestine efforts to impair, obstruct, or destroy systems, often for strategic or political ends.

Ancient and Medieval Sabotage

The earliest forms of sabotage in warfare date back to antiquity, where fire, poison, and the deliberate destruction of infrastructure were widely used to disrupt enemy operations. During the Persian-Greek Wars, Greek forces sabotaged Persian supply lines to weaken their advance and deny logistical support. In the Second Punic War, Hannibal employed sabotage with strategic precision—destroying Roman supply depots and undermining critical infrastructure to cripple enemy campaigns. These actions demonstrated sabotage’s enduring value as a tool of asymmetry and operational disruption.

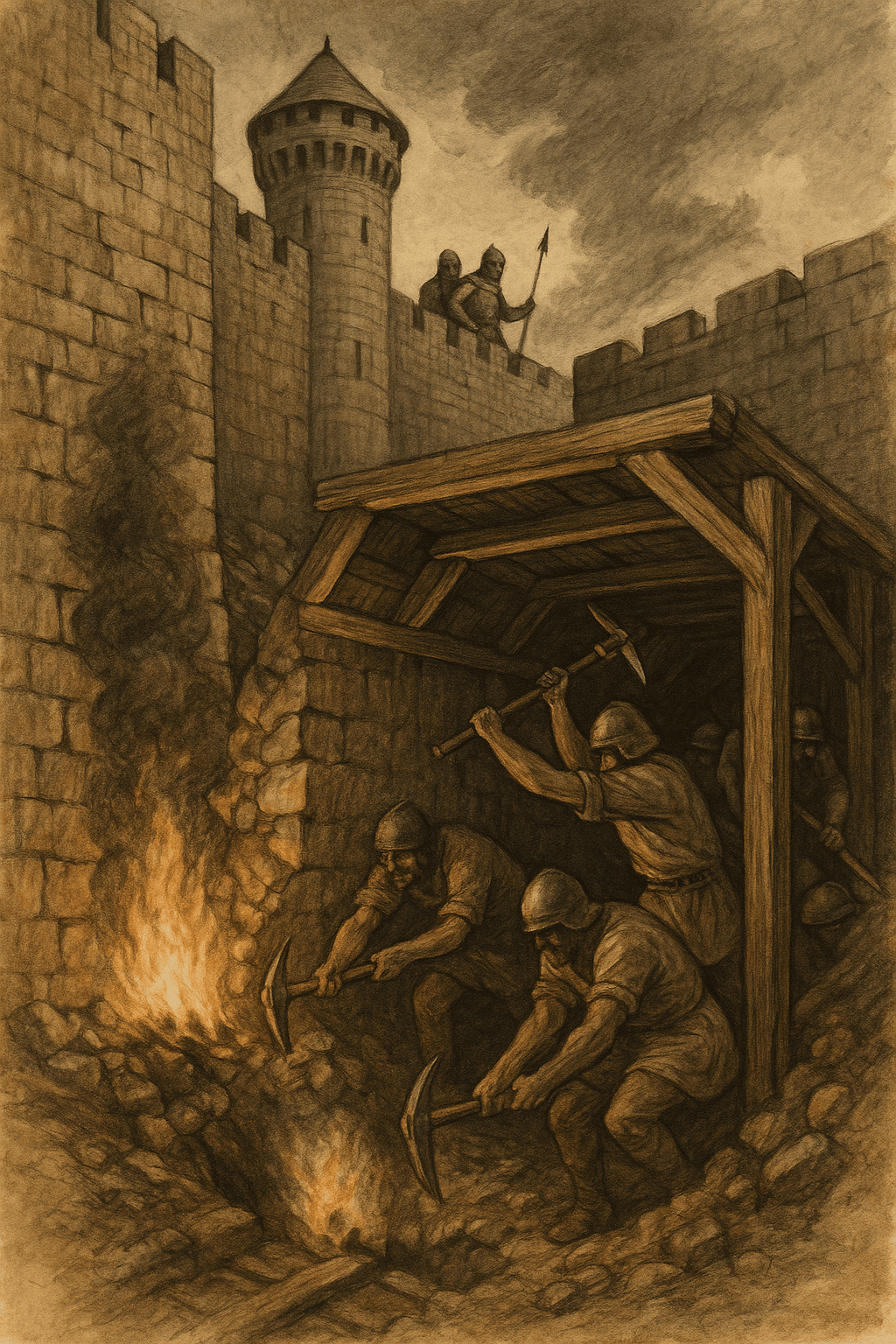

In the medieval era, sabotage became central to siege warfare. Besieging forces undermined city walls, contaminated or diverted water supplies, and destroyed fortifications to compel surrender without confrontation. Naval warfare also featured acts of sabotage, particularly during the Hundred Years’ War, when enemy vessels were deliberately sunk, burned, or disabled to obstruct movement and resupply. These early examples underscore sabotage’s role in exploiting structural vulnerabilities and degrading an opponent’s ability to project power.

Sabotage in Early Modern Warfare (1500–1800)

As warfare became more structured and resource-dependent, sabotage tactics grew in scale and complexity. During the Thirty Years’ War, opposing factions destroyed bridges, looted supply depots, and disrupted river crossings. These actions were not random. They were part of broader strategies designed to exhaust the enemy’s resources and slow their advance.

By the Napoleonic era, sabotage had become more systematic. Guerrilla fighters in the Peninsular War—especially Spanish and Portuguese irregulars—frequently attacked French communication lines and ambushed supply convoys. They also destroyed roads, bridges, and relay stations. These persistent disruptions forced Napoleon’s forces to divert troops away from the front to protect their logistics. Operating with strong local support, these irregular fighters made French control of occupied areas costly and unstable.

Sabotage during this period began to shift from isolated acts to sustained campaigns. It became a strategic tool used by decentralized forces to weaken powerful armies over time. The Peninsular War showed that even a dominant military could be ground down by persistent disruption.

Sabotage in the Industrial Age

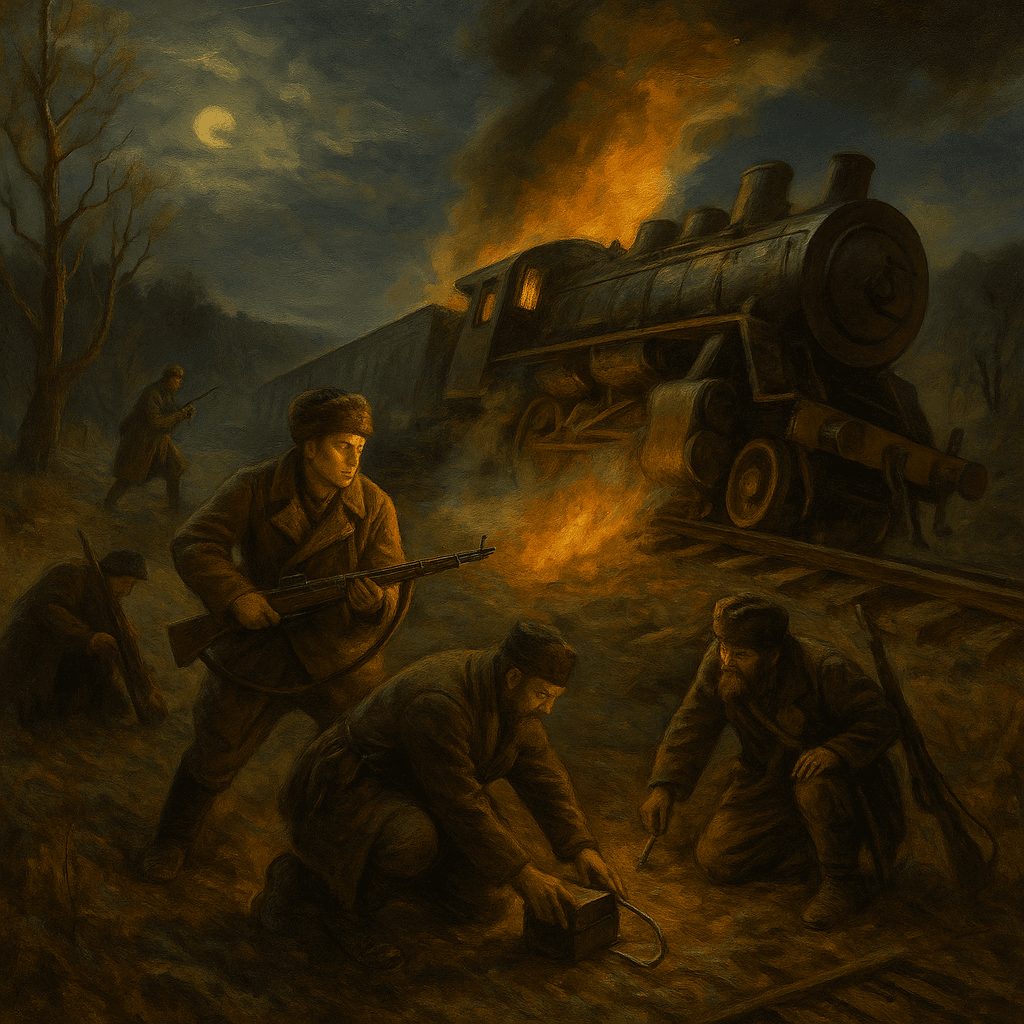

The rise of industrialization created new targets and opportunities for sabotage. As railways, factories, and communication systems became essential to military operations, disrupting them proved highly effective. During the American Civil War, both Union and Confederate forces targeted railroads, bridges, and telegraph lines. These attacks disrupted troop movements, delayed reinforcements, and severed supply chains. In several cases, sabotaged infrastructure directly influenced the outcome of key campaigns.

As warfare grew more modern, sabotage tactics became more systematic. World War I introduced industrial-scale war and, with it, more organized acts of sabotage. Intelligence services on all sides conducted covert operations behind enemy lines. A notable example was the Black Tom explosion of 1916. German agents infiltrated a munitions depot in New Jersey and ignited an explosion that damaged nearby infrastructure and injured hundreds. Their goal was to prevent American-made arms from reaching Allied forces in Europe.

These operations marked a turning point. Sabotage had shifted from a battlefield tactic to a tool of strategic disruption, capable of shaping global events from afar.

World War II: The Pinnacle of Organized Sabotage

World War II marked a high point in the scale, coordination, and impact of sabotage. Across Nazi-occupied Europe, resistance movements played a vital role in undermining the German war effort. The French Resistance frequently sabotaged railways, bridges, and supply depots to delay troop movements and disrupt logistics.

These efforts were not spontaneous. The British Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS) trained, armed, and coordinated local resistance fighters. One of the most successful missions was Operation Gunnerside, which sabotaged a heavy water facility in Norway and severely disrupted Nazi nuclear research.

Sabotage was not limited to Europe. In the Pacific Theater, Japanese forces conducted covert attacks against U.S. airfields and naval assets. At the same time, forced laborers and industrial workers in occupied factories deliberately slowed production. These acts weakened Axis military output from within and proved that sabotage could succeed even under brutal repression.

Simple Sabotage: The OSS Manual

During World War II, the Office of Strategic Services (OSS) published the Simple Sabotage Field Manual to guide everyday citizens under occupation. The manual promoted low-risk disruption tactics that anyone in factories, offices, or government buildings could perform.

These acts included misplacing tools, sabotaging machinery, and deliberately slowing workflows. Even minor disruptions—like misfiling documents or spilling liquids on important papers—created delays and confusion. The goal was to erode enemy efficiency through persistent, covert actions.

This approach allowed widespread civilian involvement. Unlike overt sabotage, these small acts often went unnoticed. Saboteurs could repeat them without drawing attention. Over time, these actions accumulated and significantly hindered the enemy’s ability to fight and govern.

Sabotage at the Three Levels of War

Sabotage operates across all three levels of war: strategic, operational, and tactical. Each level serves a different purpose, but all share the same goal—disrupting the enemy’s ability to fight effectively.

Strategic Sabotage

Targets an adversary’s overall war-making capacity. It often involves disrupting critical infrastructure, industrial output, or national-level systems. A classic example is the British bombing of Germany’s Ruhr Valley dams in Operation Chastise. This strike severely limited German energy production. In modern times, cyberattacks serve a similar role. The Colonial Pipeline attack disrupted fuel supplies across the U.S. East Coast and revealed vulnerabilities in civilian energy infrastructure.

Operational Sabotage

Affects enemy movements, logistics, and coordination within a theater of war. The French Resistance sabotage of railways ahead of the Normandy landings delayed German reinforcements. These actions directly supported Allied planning and enabled greater success on the battlefield.

Tactical sabotage

Occurs at the unit or mission level. It includes cutting communication lines, planting explosives, or disabling vehicles before an engagement. The Viet Cong’s use of booby traps in Vietnam is a clear example. These small-scale actions weakened morale and inflicted steady attrition.

Together, these levels show that sabotage is not a single act. It is a flexible and powerful tool—capable of shaping military outcomes from the ground up.ge in achieving diverse military objectives.

Cold War Sabotage and Proxy Conflicts

During the Cold War, sabotage became a defining feature of proxy wars, covert operations, and guerrilla campaigns. Both the United States and the Soviet Union backed insurgent groups around the world, turning sabotage into a key instrument of indirect conflict. These groups often targeted infrastructure—bridges, power stations, supply depots, and communication lines—to weaken established governments and delay military responses.

The Viet Cong in Vietnam provides a clear example. They employed sabotage extensively to disrupt U.S. military operations, destroy fuel and ammunition stores, and create uncertainty in American supply lines. Their use of booby traps, tunnel systems, and infrastructure attacks allowed them to fight a stronger opponent on asymmetric terms.

This era also marked the rise of technological sabotage. Early forms of electronic warfare emerged, as did rudimentary hacking efforts. Communications networks, radar systems, and weapons platforms became new targets. These developments signaled a shift from purely physical sabotage to more sophisticated, non-kinetic operations.

The Cold War laid the foundation for modern sabotage doctrine. It proved that sabotage could function across ideological lines, geographic theaters, and technological domains—making it a core tactic in both irregular warfare and statecraft.

Modern Sabotage in 21st-Century Warfare

In the 21st century, sabotage has increasingly shifted toward digital and hybrid forms. One of the most prominent examples is the Colonial Pipeline attack, a major cyber operation that disrupted fuel distribution across the Eastern United States. This event underscored the growing importance of cyber sabotage in targeting critical infrastructure without physical confrontation.

Kinetic sabotage continues as well. Armed groups and state-backed actors have targeted infrastructure to destabilize governments or delay military operations. ISIS has repeatedly sabotaged oil pipelines, water facilities, and power grids to undermine stability and weaken opponents. In Yemen, Houthi forces have launched missile and drone attacks on oil facilities and ports, blurring the line between sabotage and strategic strike.

Sabotage today is no longer limited to explosives or tools. It now includes malware, drones, and insider threats. Whether digital or physical, modern sabotage remains a powerful force for disruption in both declared wars and grey zone conflicts.

Conclusion

The history of sabotage in warfare reveals its persistent value as a tool for disruption. From ancient attacks on supply lines to the strategic use of cyber sabotage today, this tactic has consistently adapted to meet the demands of changing technology and conflict. Sabotage offers a way to weaken the enemy without open confrontation, often requiring fewer resources and yielding disproportionate effects.

As warfare continues to evolve—especially in digital and hybrid domains—sabotage will likely play an even greater role. Its growing presence in cyber operations also raises new legal, ethical, and strategic concerns. Nations and non-state actors alike are investing in capabilities to exploit this method of warfare.

To explore the foundations of sabotage and access-related publications, see our brief guide to sabotage.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply