About the Author:

Moe Gyo is a writer and consultant working with various ethnic organizations in Myanmar. He writes from the Thai–Myanmar borderlands, drawing on years of direct engagement with communities navigating conflict, displacement, and disrupted health systems. His work reflects firsthand observation of how resilience and informal support networks emerge in areas affected by irregular warfare.

This article is a reader-contributed submission to The Resistance Hub.

From Governance Competition to Market Structure

Part I established insurgency as a form of strategic competition over governance rather than a contest of destruction. It showed how armed actors endure, expand, or fail based on their ability to provide security, justice, public goods, and legitimacy more credibly than their rivals, and how civilians, operating under coercion and uncertainty, allocate compliance within a contested governance marketplace. Viewed through this lens, violence functions not as an end in itself, but as a mechanism for shaping incentives and enforcing authority within a broader competitive system.

Yet understanding insurgency as a marketplace explains why conflict persists without explaining how its structure constrains strategic choice. Governance competition does not occur on a blank slate. It is shaped by enduring structural forces that determine how easily new challengers emerge, how intensely rivals compete, how much leverage civilians possess, how dependent actors are on external suppliers, and what alternative sources of order cap any single authority’s control. These forces shape outcomes independently of leadership quality, ideology, or battlefield performance.

To analyze these structural constraints, Part II applies Porter’s Five Forces framework to the war marketplace. While originally developed to explain competition in commercial industries, the framework is well suited to irregular conflict because it focuses not on individual actors but on the competitive environment in which they operate. Transposed to insurgency, “profitability” corresponds to authority, compliance, and durability; “market share” to civilian control; and “entry barriers” to the costs of establishing and enforcing governance.

By mapping rivalry, entry, substitution, and bargaining power onto governance competition, this section shows why some insurgencies regenerate endlessly, why others fragment into warlordism, and why certain conflicts resist decisive resolution regardless of military effort. Part I defined insurgency as competitive governance. Part II explains why the structure of that competition so often favors instability and what must change for durable authority to emerge.

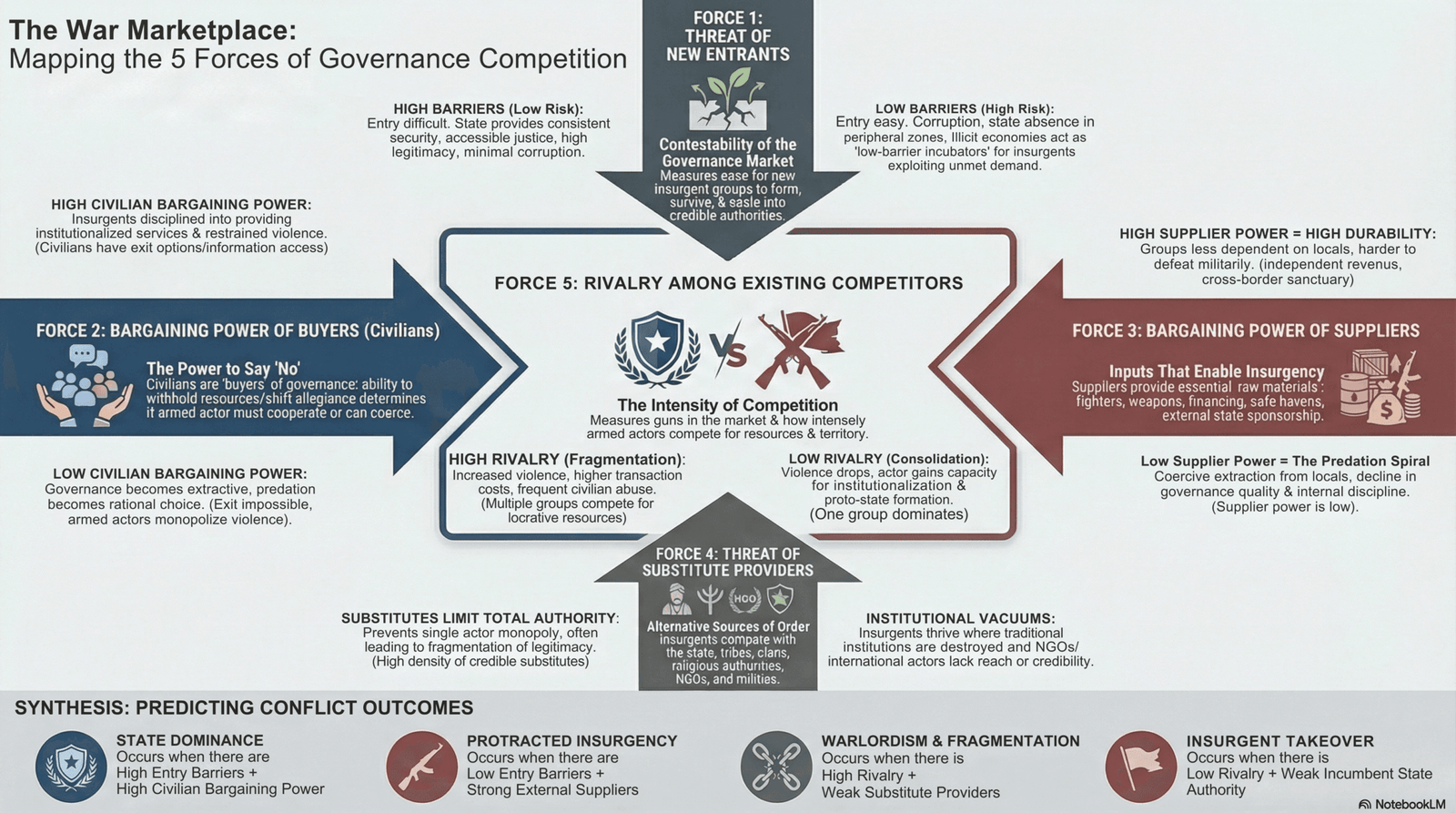

Among the structural pressures shaping governance provision, rivalry between existing providers is the force through which all others are expressed. Barriers to entry, civilian bargaining power, external suppliers, and available substitutes condition the competitive environment, but it is rivalry that translates these forces into lived political order. Civilians experience rivalry through overlapping taxation, competing courts, contested security provision, and the calibrated use of violence and restraint by rival authorities.

Force 1: Threat of New Entrants

When Governance Markets Are Contestable

The threat of new entrants captures how easy it is for armed groups to form, survive, and scale. In war, “entry” means the ability of an insurgent organization to establish itself as a credible alternative authority.

High Barriers to Entry (Low Insurgency Risk)

Entry barriers are high when the state:

- Provides consistent security.

- Delivers accessible justice.

- Limits corruption and predation.

- Maintains intelligence penetration.

- Enforces credible punishment against challengers.

- Retains legitimacy narratives that resonate locally.

In these environments, insurgent startup costs are prohibitive. Recruitment is risky, financing is difficult, and early-stage groups are rapidly disrupted.

Low Barriers to Entry (High Insurgency Risk)

Entry barriers collapse when the state:

- Is corrupt, exclusionary, or repressive.

- Cannot secure peripheral regions.

- Fragments along factional or ethnic lines.

- Fails to provide justice or basic services.

- Allows illicit economies to flourish.

These failures create market inefficiencies. Insurgents do not create demand; they exploit unmet demand for governance.

Borderlands, urban slums, refugee camps, and marginalized rural zones function as low-barrier incubators where groups can:

- Recruit cheaply

- Experiment with governance

- Build parallel revenue streams

- Avoid early repression

Proposition 1: The lower the effectiveness of state governance, the lower the barriers to insurgent entry and the higher the probability of insurgent emergence.

Force 2: Bargaining Power of Buyers (Civilians)

Who Civilians Can Say “No” To

In the war marketplace, civilians are the primary buyers of governance. Their bargaining power determines whether armed actors must compete or can simply coerce.

High Civilian Bargaining Power

Buyer power is high when civilians:

- Can shift allegiance with manageable risk.

- Have multiple governance options.

- Possess access to information.

- Can withhold intelligence or resources.

- Can exit (migration, neutrality, and substitution).

In these environments:

- Insurgents invest in courts, discipline, and services.

- Abuse is punished internally.

- Governance becomes institutionalized.

- Violence is selective and restrained.

- Competition disciplines behavior.

Low Civilian Bargaining Power

Buyer power collapses when:

- Switching sides invites retaliation.

- Exit is impossible.

- Armed actors monopolize violence.

- Surveillance and collective punishment dominate.

Here:

- Governance becomes extractive.

- Violence substitutes for legitimacy.

- Compliance is coerced, not earned.

- Predation becomes rational.

Proposition 2: High civilian bargaining power incentivizes cooperative governance; low bargaining power produces coercion-heavy control models.

Force 3: Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Who Enables Insurgency

Suppliers are the inputs that make insurgency viable:

- Fighters and administrators

- Weapons and explosives

- Financing and logistics

- Safe havens and transit routes

- External sponsors

- Ideological legitimacy producers

High Supplier Power

Supplier power is high when insurgents have:

- Independent revenue streams (narcotics, mining, smuggling).

- Cross-border sanctuary.

- State sponsors.

- Diaspora funding.

- Autonomous recruitment pipelines.

High supplier power:

- Reduces dependence on civilians.

- Lowers accountability.

- Increases resilience.

- Enables prolonged conflict

Groups with strong suppliers can survive despite civilian hostility.

Low Supplier Power

When suppliers are constrained:

- Recruitment becomes harder.

- Financing shifts toward coercive extraction.

- Governance quality declines.

- Internal discipline erodes.

This often produces a predation spiral that alienates civilians.

Proposition 3: Autonomous supplier networks are a primary determinant of insurgent durability and resistance to military defeat.

Force 4: Threat of Substitute Governance Providers

Who Else Can Govern

Insurgents do not compete only with the state. They compete with substitutes:

- Tribal or clan systems

- Religious authorities

- Local militias

- Criminal protection rackets

- NGOs and humanitarian actors

- International peacekeepers

- Private security providers

High Substitute Density

Where substitutes are credible:

- Insurgents struggle to monopolize authority.

- Governance fragments.

- Legitimacy is diluted.

- Consolidation is delayed or prevented.

Substitutes can undermine both insurgents and the state.

Low Substitute Density

Insurgents thrive where:

- Traditional institutions are destroyed.

- NGOs lack reach or credibility.

- Militias are predatory.

- The state is absent or abusive.

Institutional vacuums favor insurgent governance.

Proposition 4: Effective substitute governance providers reduce insurgent appeal and increase fragmentation of authority.

Force 5: Rivalry Among Existing Competitors

How Many Guns Are in the Market

Rivalry measures the intensity of competition among armed actors.

High Rivalry

Occurs when:

- Multiple insurgent groups compete.

- Ethnic or ideological fragmentation exists.

- Resources are lucrative and divisible.

- External sponsors back different proxies.

Effects:

- Increased violence

- Reduced governance investment

- High transaction costs

- Civilian abuse

- Organizational instability

Low Rivalry

Occurs when:

- One insurgent group dominates.

- Hierarchies are enforced.

- Territory is consolidated.

Effects:

- Lower violence

- Greater governance capacity

- Stronger legitimacy claims

- Higher risk of insurgent proto-state formation

Proposition 5: Higher rivalry degrades governance capacity; lower rivalry enables institutionalization and durability.

Synthesis: Reading the War Environment Structurally

Taken together, the Five Forces define the structural environment in which war is fought. They do not describe individual actors or tactical choices; they explain the conditions that shape who can enter the conflict, how authority is exercised, how long organizations endure, and how control fragments or consolidates over time.

- Entry barriers determine who can credibly contest authority.

- Buyer (civilian) power determines how governance is exercised.

- Supplier power determines organizational endurance.

- Substitutes determine the ceiling on authority any actor can claim.

- Rivalry determines the coherence, discipline, and violence of competition.

Different configurations of these forces produce recurring and predictable outcomes:

- High entry barriers + high civilian bargaining power → monopoly restoration and state dominance

- Low entry barriers + strong suppliers → protracted insurgency and regeneration

- High rivalry + weak substitutes → fragmentation and warlordism

- Low rivalry + weak incumbent authority → insurgent takeover

What appears as strategic failure or success at the tactical level is often the product of these structural conditions rather than leadership quality or battlefield performance. Reading the war environment structurally, therefore, becomes a prerequisite for strategy rather than an academic exercise.

Conclusion: Structure as the Hidden Determinant of Strategic Outcomes

Insurgency endures not because states lack military power, but because they fail to dominate the governance marketplace in which authority is contested. Wars are not decided solely by killing enemy fighters or clearing terrain; they are decided by patterns of civilian compliance over time. As Part I argued, insurgency is best understood as a competitive process in which states and armed challengers vie to supply security, justice, public goods, and legitimacy under conditions of institutional breakdown and coercion. Part II has shown that the outcomes of this competition are not arbitrary. They are structured.

Applying Porter’s Five Forces to the war marketplace clarifies why similar counterinsurgency efforts produce radically different results across cases. Low barriers to entry explain insurgent regeneration and fragmentation; civilian bargaining power disciplines governance behavior and sustains hedging; supplier networks determine organizational endurance; substitute institutions cap authority and dilute monopoly control; and rivalry among governance providers translates these pressures into everyday patterns of violence, restraint, and compliance. Together, these forces shape the competitive environment within which all strategic choices are made.

Seen in this light, many persistent puzzles of irregular warfare become intelligible. Militarily weaker insurgents outlast stronger states not because they fight better, but because the structure of the governance market favors challengers. Governance reforms fail not because civilians reject them, but because competitive conditions render them non-credible. Violence succeeds or backfires depending not on its intensity, but on how it alters rivalry, entry barriers, and civilian bargaining power. What appears chaotic at the tactical level reflects predictable equilibria at the structural level.

Most importantly, this analysis clarifies a critical distinction: structure shapes what strategies are viable, but it does not determine how actors respond. The Five Forces define the competitive environment, but they do not dictate behavior. States and insurgents are strategic actors who attempt, often imperfectly, to manipulate these forces in their favor: raising or lowering barriers to entry, altering civilian leverage, securing or severing suppliers, eliminating substitutes, and managing rivalry. Some succeed temporarily; many fail systematically.

Understanding war structurally is therefore not an academic exercise. It is a prerequisite for strategy. Without diagnosing the underlying market forces, interventions mistake symptoms for causes and tactics for solutions. With that diagnosis in hand, strategy becomes intelligible as an effort to reshape competition rather than simply win battles.

Part III—Strategy in the War Marketplace turns from structure to action. It examines how states and insurgents pursue strategy within the war marketplace, how they attempt to manipulate the same five forces from opposing positions, and why asymmetries in constraint and leverage produce recurring patterns of success and failure. If Parts I and II explain what insurgency is and why it persists, Part III explains how it is fought and why so many efforts to defeat it collapse under their own strategic misreading.

Editorial Note:

This article is a reader-submitted contribution. The Resistance Hub publishes it to present individual analytical perspectives informed by experience in conflict-affected regions, including how irregular or asymmetric approaches are understood and adapted in practice. The views and interpretations expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the positions of The Resistance Hub. Publication does not imply endorsement of any actor, organization, or specific claim.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.