Overview of the Events

In late 2025, elements linked to the security services in Guinea-Bissau attempted to seize control of key state facilities in the capital, Bissau. The episode unfolded over a short time window and did not escalate into sustained fighting. Loyal units retained control of core government sites, and the attempt collapsed before it could consolidate momentum.

President Umaro Sissoco Embaló publicly characterized the events as a coup attempt involving political and military actors. Security forces moved quickly to reassert control, arrests followed, and heightened security measures were imposed around sensitive locations. There was no verified evidence of large-scale civilian participation, nor were there indications of coordinated action beyond a limited circle of actors.

Within days, the immediate threat subsided. Government institutions continued to function, borders remained open, and international actors signaled recognition of the sitting government. The episode ended with a return to a tense status quo.

Preconditions for Revolution

The attempted coup did not emerge in a vacuum. Several recurring structural conditions made such an effort conceivable. These conditions reflect long-standing patterns of elite competition, weak civilian oversight of the security sector, and unresolved questions of political legitimacy rather than any sudden rupture. In such environments, the use of force remains an available instrument for political bargaining when institutional channels are viewed as ineffective or closed.

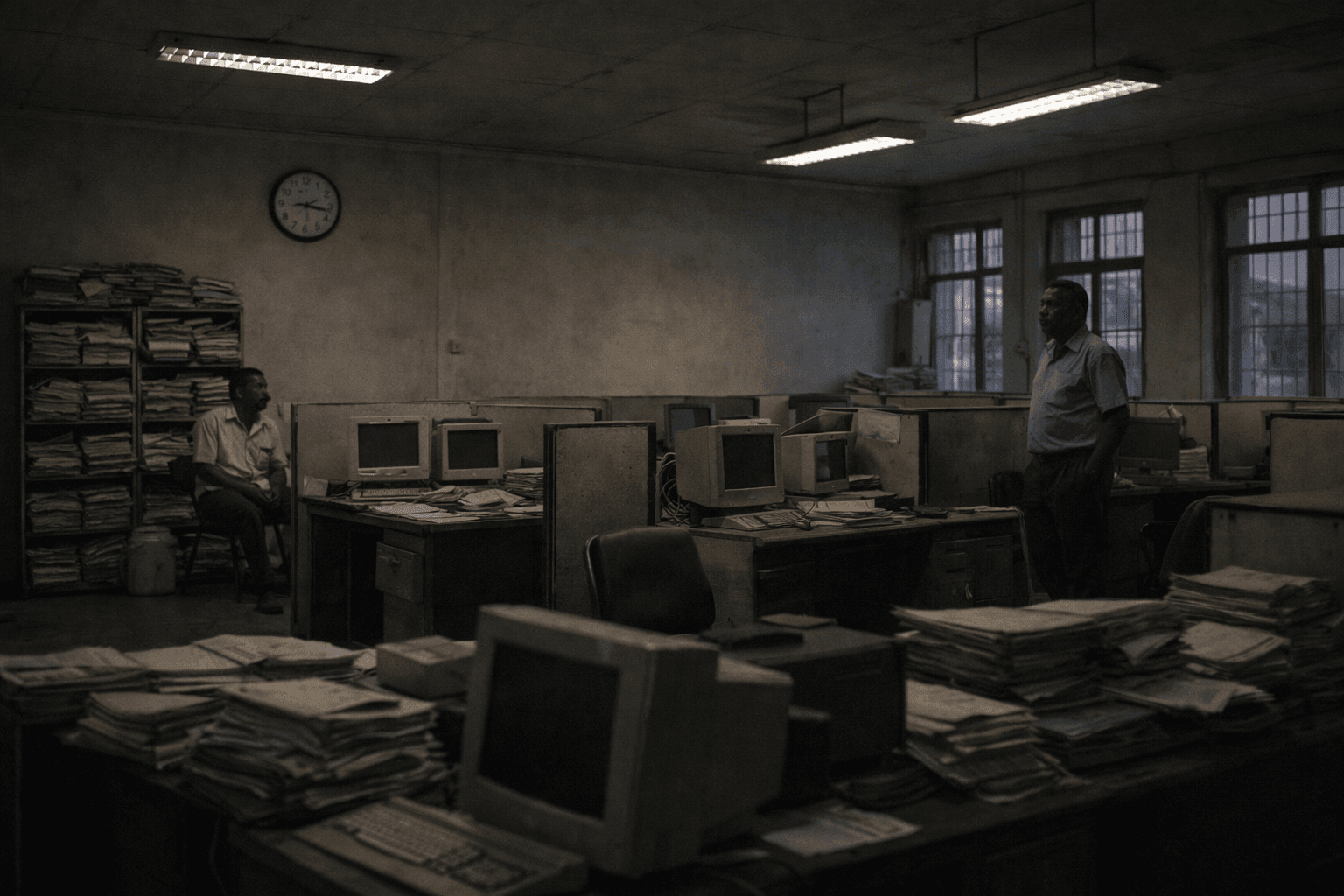

Civil-military politicization remains a defining feature of Guinea-Bissau’s post-independence history. The armed forces have long operated as political stakeholders rather than strictly professional institutions. This blurring of roles lowers the threshold for military involvement in elite disputes.

Elite factionalism also played a central role. Power struggles in Guinea-Bissau tend to occur within narrow political and security circles. In this context, force becomes an arbitration mechanism among elites rather than a tool for mass political transformation.

A perceived legitimacy deficit contributed to the timing. Public dissatisfaction with governance exists, but it is uneven and not ideologically organized. For coup plotters, this creates an assumption that decisive action at the top can succeed without popular mobilization. This dynamic aligns with the concept of relative deprivation, where frustration is driven less by absolute hardship than by perceived disparities in access, status, and opportunity among elites and connected networks. In such contexts, grievance concentrates upward, encouraging action by those who feel excluded from power rather than mass-based revolt from below.

Finally, regional contagion effects mattered. The recent succession of successful coups in parts of the Sahel has normalized unconstitutional seizures of power as a viable option. Even where local conditions differ, precedent lowers psychological barriers and reshapes expectations among would-be plotters.

Taken together, these factors created an environment where a coup attempt appeared plausible to a limited group, even if broader conditions were unfavorable.

Why Did it Fail?

The same structural environment that enabled the attempt also constrained its success.

The most immediate factor was a lack of unified command and control. The plotters failed to demonstrate coordinated leadership or to seize decisive nodes simultaneously. Without control of communications, senior command figures, and reinforcement pathways, momentum dissipated quickly.

Insufficient security force buy-in proved decisive. Successful coups in the region typically hinge on rapid alignment across key military and internal security units. In this case, loyalty remained fragmented, and enough units adhered to the existing chain of command to blunt the effort.

Equally important was the absence of a popular legitimacy trigger. There was no mass protest, strike activity, or civilian mobilization that might have overwhelmed state response. Administrative systems continued to function, denying the plotters the appearance of inevitability that coups often rely on.

Finally, external signaling raised the perceived costs of success. Swift regional and international condemnation, particularly from West African partners, reinforced the likelihood of diplomatic isolation and potential sanctions. For actors already operating with limited domestic legitimacy, this narrowed the risk calculus further. The failure reflected structural constraints that the plotters were unable to overcome.

The Legacy of Coups in Africa

Coups have been a recurring feature of African politics since independence, but their character has evolved. Earlier interventions often claimed ideological justification or revolutionary intent. Contemporary coups are more frequently transactional, aimed at redistributing power among elites rather than reshaping political systems.

In this context, coups function less as causes of instability than as symptoms of institutional weakness. Where mechanisms for elite competition, succession, and accountability are underdeveloped, force becomes a fallback option.

The recent emergence of a so-called coup belt has reinforced this dynamic, but it has also obscured important variation. Failed coups, like the one in Guinea-Bissau, reveal where institutions retain partial coherence and where deterrence still operates. They show not strength, but friction.

Analytically, failed coups are often more informative than successful ones. They expose fault lines without collapsing the system, offering insight into what still holds and what is beginning to erode.

What’s Next

The failed coup attempt in Guinea-Bissau does not signal democratic consolidation, nor does it place the country outside the broader regional pattern. It indicates a temporary equilibrium in which competing forces remain unresolved.

The conditions that enabled the attempt persist, including politicized security institutions and elite rivalry. At the same time, the factors that caused its failure demonstrate that Guinea-Bissau has not yet crossed key thresholds associated with sustained instability. The lesson is straightforward. Failed coups are not endpoints. They are diagnostics. They show where pressure is building, where institutions still function, and where the next attempt may differ from the last.