About the Author:

Moe Gyo is a writer and consultant working with various ethnic organizations in Myanmar. He writes from the Thai–Myanmar borderlands, drawing on years of direct engagement with communities navigating conflict, displacement, and disrupted health systems. His work reflects firsthand observation of how resilience and informal support networks emerge in areas affected by irregular warfare.

Civilians are not mere bystanders in irregular warfare: they are strategic terrain. Armed actors, both state and non-state, routinely seek to control, coerce, or punish civilian populations to achieve military and political objectives. Access to healthcare and basic survival infrastructure in these environments becomes a contested resource.

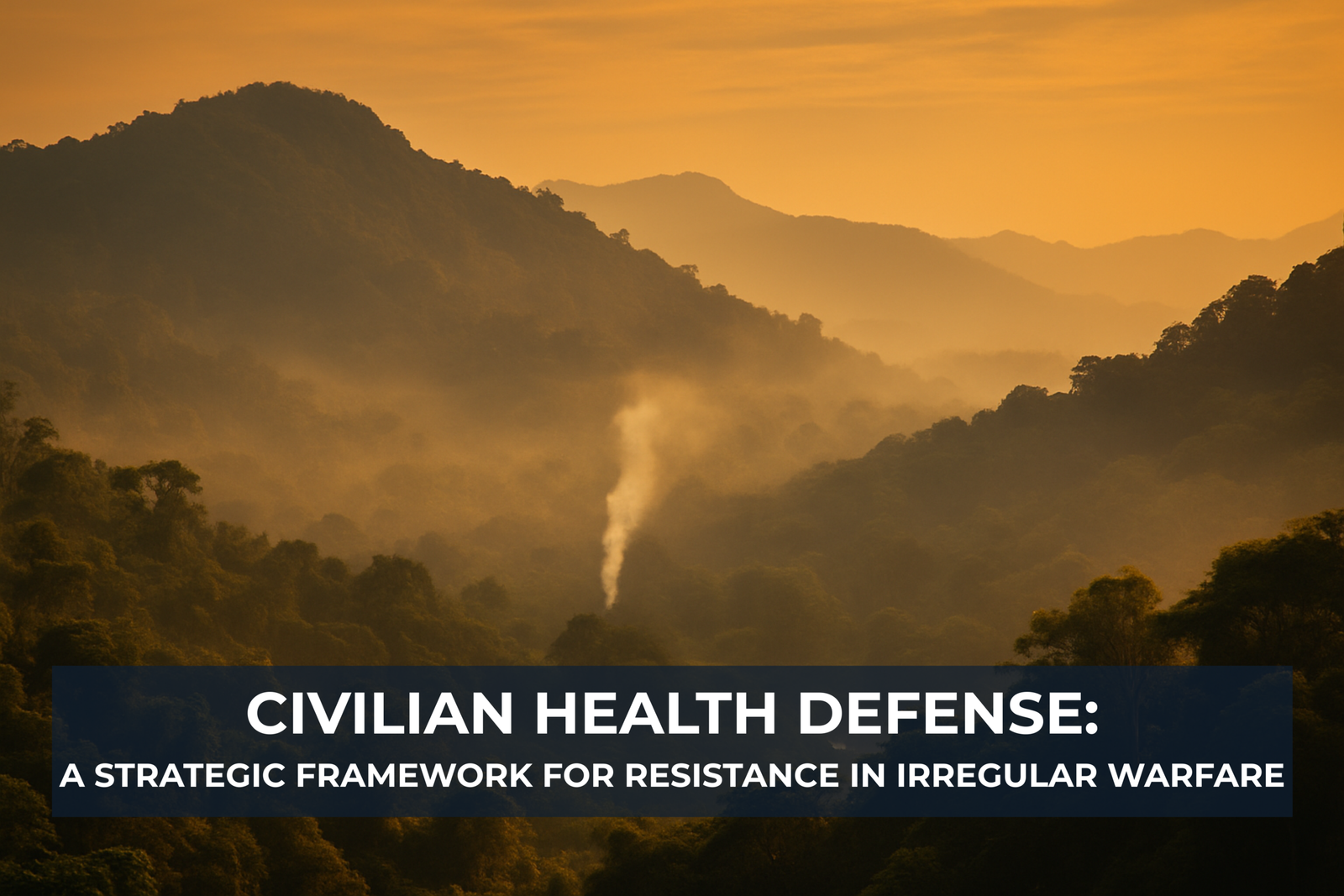

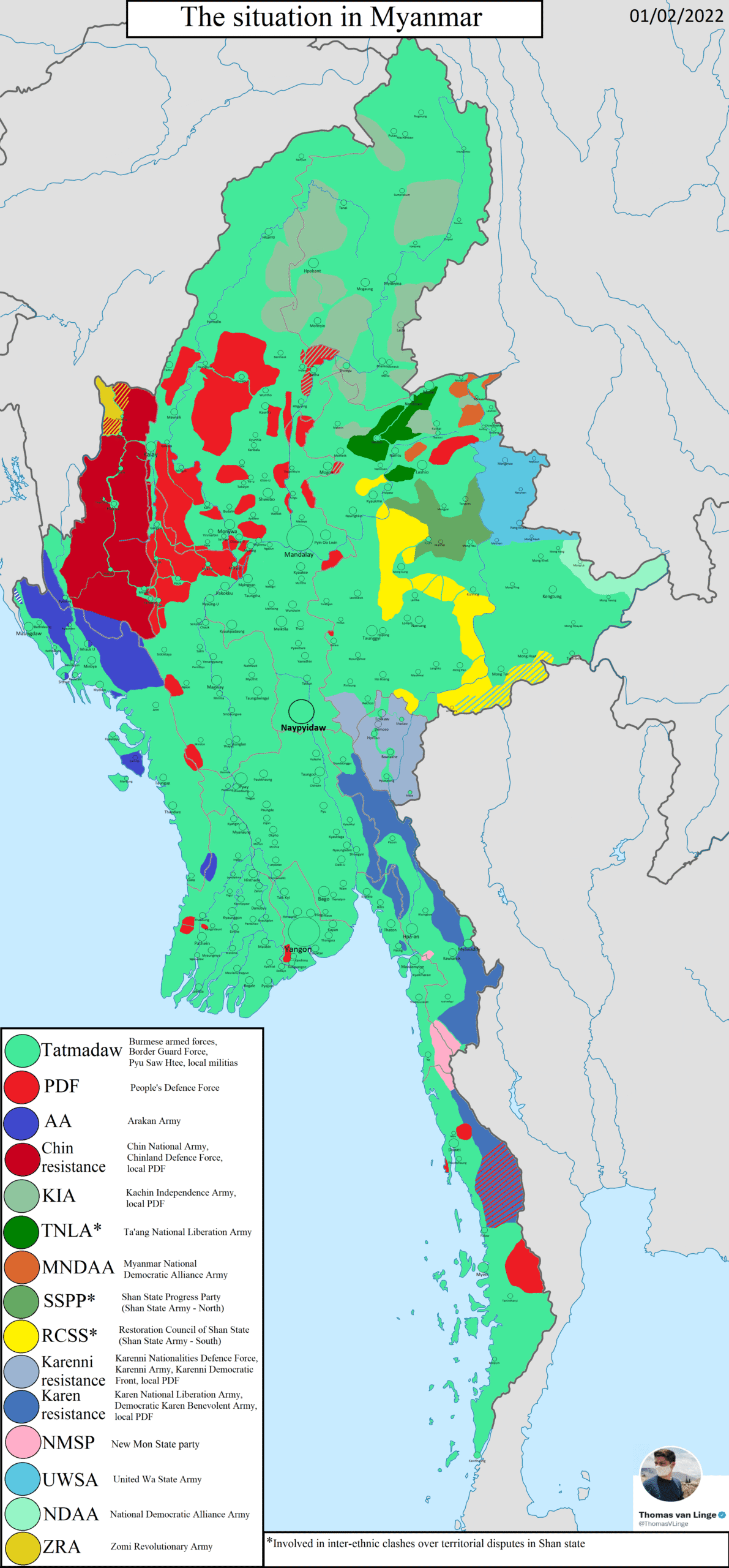

In the ethnic conflict zones of Myanmar (aka Burma), where formal health systems may be absent and violence is endemic, it has become necessary to develop an unconventional form of civilian defense: health-based resistance and resilience. The Civilian Health Defense (CHD) Program, developed at the Back Pack Health Worker Team (BPHWT), located along the Thai-Myanmar border, amid Myanmar’s protracted insurgencies, represents a grassroots strategy to protect civilian populations from the cascading health consequences of irregular warfare. The BPHWT recruits, trains, organizes, equips, deploys, and sustains 120 mobile health teams in areas controlled by non-state actors in Myanmar.

CHD offers a case study of localized resilience in an irregular warfare setting and proposes broader lessons for military planners and civil resistance strategists. It is a community-led defense framework that enables populations to survive, adapt, and resist through health.

Source: Thomas van Linge, Military Situation in Myanmar, February 2022 (CC BY 4.0).

CHD Operating Environment

Myanmar has endured more than seventy years of armed conflict, marked by ethnic resistance, military crackdowns, and widespread repression. In its attempts to dismantle non-state opposition, the Myanmar military has relied on the “Four Cuts” counter-insurgency strategy, severing access to food, funds, intelligence, and recruits, to isolate resistance movements from their civilian support base. This approach targets civilian life at its core, turning survival itself into a battlefield. Armed actors use health insecurity—displacement, forced labor, and starvation—not only as byproducts of conflict but as calculated strategies of control. In these environments, civilians face layered threats to life, health, and cohesion.

Soldier violence and repression

Soldier violence and repression remain central to this coercive apparatus. Direct violence, including beatings, rapes, gunshots, shelling, bombing, and the use of landmines, results in high rates of trauma-related injuries and deaths. Wounds from military ordnance frequently lead to amputations, permanent disabilities, or fatalities, particularly during military incursions or village raids. Women and children face disproportionate risks. Maternal deaths often result from trauma or blocked access to care, while infants and children are killed or harmed directly or succumb to injuries and neglect during periods of instability. When communities are forced to flee into forests, they are further exposed to malaria, respiratory infections, and waterborne diseases such as diarrhea, compounding the burden of both trauma and preventable illness.

Forced displacement and relocation

Forced displacement and relocation, often the result of village destruction, burning of homes, and mining of agricultural fields and trails, leave civilians without shelter, sanitation, or access to care. The act of fleeing itself can be deadly: people are wounded by military ordnance while escaping, and survivors often end up in makeshift shelters where diseases like acute respiratory infections, diarrhea, dysentery, worm infestations, and malaria spread rapidly. Food becomes scarce, and the lack of nutrition leads to anemia, night blindness, and death, particularly among pregnant women and young children. These outcomes are not incidental; they are embedded within a military strategy that weaponizes movement and isolation to weaken resistance.

Forced labor

Forced labor further degrades civilian health and autonomy. Civilians, including children and the elderly, are routinely conscripted to serve in military units by being forced to build infrastructure, transport supplies, or perform other hazardous tasks. These conditions expose individuals to injury and even death from overwork, abuse, or harsh environments. Extended labor under duress often occurs with minimal food, contributing to malnutrition and anemia. Pregnant women and caregivers are especially at risk, as forced labor removes them from familial and communal safety nets, directly contributing to maternal and infant mortality. Laborers operating in malaria-endemic forests without shelter or protective gear also face heightened risks of disease and long-term health deterioration.

Food insecurity

Food insecurity, both an outcome and instrument of repression, is strategically inflicted by destroying crops, mining agricultural fields, blockading aid, and preventing market access. These tactics intentionally undermine self-sufficiency, causing communities to experience chronic hunger, weakened immune systems, and higher rates of preventable disease. Malnutrition, anemia, and night blindness become endemic, while weakened immunity increases susceptibility to malaria, respiratory infections, and diarrhea. For children and pregnant women, the stakes are particularly high: food insecurity directly correlates with rising maternal and infant mortality.

These overlapping forms of structural and physical violence illustrate how Myanmar’s irregular warfare environment uses health insecurity as a deliberate tool of war. The destruction of clinics, attacks on medics, and blockades of humanitarian aid are not merely collateral; they are methods of disabling the population’s ability to endure, resist, or recover.

CHD emerged as a strategic civilian response to these cumulative threats, transforming health resilience into a method of civilian protection, mobility, and resistance. It addresses the very systems that irregular warfare seeks to dismantle by equipping communities with tools to survive trauma, respond to disease, and maintain social cohesion even under siege. In this context, health becomes a weapon of resistance: a way to deny adversaries the strategic advantage of fear, fragmentation, and dependency.

A Health-Based Strategy for Civilian Resistance

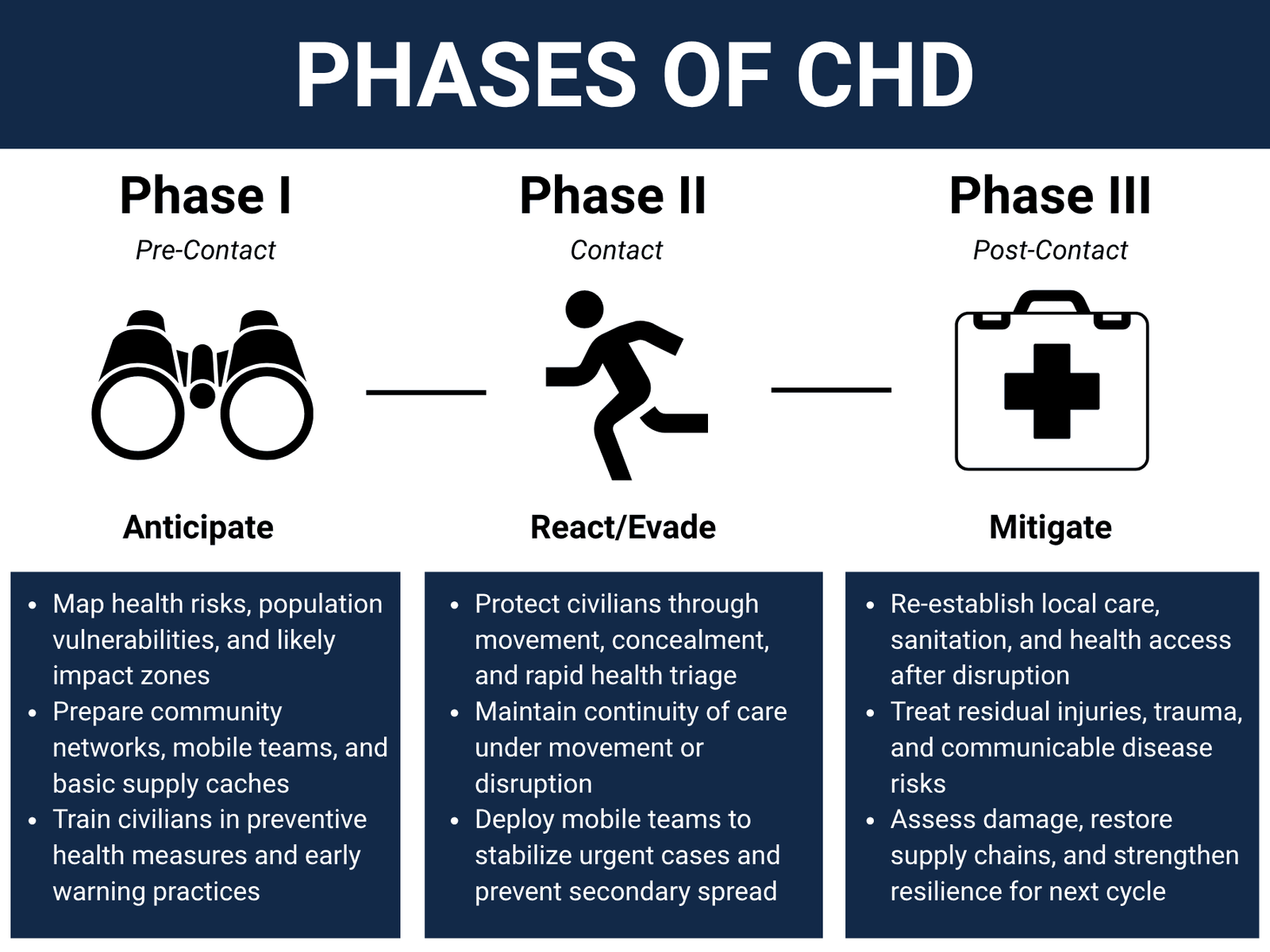

The CHD framework is designed to protect civilian populations in conflict zones through health-based resilience, with a focus on local capacity-building, preparation, response, and recovery. It is not a rigid, pre-structured program but rather an evolving, flexible system that adapts to the specific realities of each community and conflict environment. The framework is structured around three distinct but interconnected phases: Anticipate (Pre-Contact Preparedness), React/Evade (During Contact), and Mitigate (Post-Contact Recovery). Each of these phases addresses different stages of the conflict cycle, from the initial signs of impending violence to the recovery and rebuilding of health systems after attacks or displacement.

Phase I: Anticipate (Pre-Contact Preparedness)

In the first phase, the focus is on preparing communities for the possibility of violence or forced displacement before it occurs. The idea is to anticipate threats, reduce risks, and prepare health measures that can be deployed swiftly when needed. This phase involves a deep commitment to preemptive action and health preparedness, ensuring that communities are not caught off-guard by the unpredictable nature of irregular warfare.

The initial step is to establish early warning systems or threat monitoring networks within the community. These networks help track the movements of armed actors—whether state or non-state forces—allowing villagers to receive advance notice of impending attacks or military operations. Such systems are critical in a conflict setting, where the element of surprise is often a tactic used to destabilize civilian populations. With this forewarning, villagers can take immediate protective action and prepare for displacement if necessary.

Another key component of the Anticipate Phase is the identification and establishment of displacement sites. These sites are selected based on their ability to conceal the population and provide access to essential resources like water, food, and shelter. Sites are chosen strategically to minimize exposure to hostile forces while ensuring that community members can sustain themselves in the event of displacement.

To ensure that these displacement sites are prepared, health caches are pre-positioned. These caches include both traditional and modern medicines, maternal care kits, clean water vessels, and shelter supplies. These resources are essential for supporting the community’s health and survival during periods of instability, preventing outbreaks of disease, and reducing the burden of trauma-related injuries.

In addition to physical preparation, the community engages in evacuation drills and mine risk education. These drills ensure that villagers are familiar with evacuation routes and protocols, reducing the risks associated with fleeing under duress. In addition, villagers are trained in survival skills under stress, including the ability to navigate displacement sites, avoid conflict zones, and mitigate the risk of injury from mines or other hazards.

Training programs are conducted to equip local health workers with the necessary skills to respond to medical emergencies and manage public health crises. These programs cover a wide range of topics, from first aid and disease prevention to maternal care and emergency medical response. In addition, health screening and preventive care (e.g., immunizations and contraception measures, e.g., supplies of oral contraceptive pills) are prioritized during periods of calm, ensuring that the community remains prepared even during relatively peaceful periods.

Phase II: React/Evade (During Contact)

When violence or military engagement becomes imminent, the second phase of the CHD framework is activated. This phase emphasizes immediate action and minimizing exposure to hostile forces while ensuring that health resilience remains intact. The community must react quickly and efficiently, utilizing the preparedness measures established in the Anticipate Phase.

The first priority is the activation of evacuation plans, which were developed earlier in the process. Villagers, trained in evacuation routes and protocols, quickly flee to the pre-identified displacement sites, minimizing their exposure to the advancing troops. In these tense moments, pre-packed health evacuation kits—containing essential medical supplies and communication tools—are carried to minimize reliance on external aid. These kits ensure that the community has the resources to respond to injuries, manage health risks, and maintain communication during the chaos of displacement.

In addition, exposure to hostile forces must be minimized. Communities use coordinated movement and concealment techniques to avoid re-encounters with armed actors. This may involve moving under the cover of night, utilizing local knowledge of the terrain. Early warning systems continue to monitor troop movements, providing real-time updates that help prevent dangerous encounters.

Phase III: Mitigate (Post-Contact Recovery)

Once the immediate threat has subsided and the community has been displaced or directly impacted, the third phase of the CHD framework focuses on post-contact recovery and restoration of health systems. The goal is to manage the aftermath of violence, ensure the community’s survival, and set the stage for long-term health resilience.

At this stage, the immediate health priorities shift to addressing disease outbreaks, treating injuries, and combating malnutrition. Given the heightened risk of waterborne diseases, respiratory infections, and malaria, these conditions are addressed promptly to avoid further loss of life and to prevent any additional destabilization of the community. Special attention is given to vulnerable groups, including children, the elderly, and pregnant women, who are at heightened risk of complications during times of displacement.

Sanitation systems are restored to prevent disease spread, and clean water access is re-established as a matter of urgency. This is vital not only for preventing illness but also for maintaining the psychological resilience of the population. When people feel that their basic needs are met and their health is protected, their ability to endure the trauma of displacement and violence is significantly improved.

Another critical element of the Mitigate Phase is the marking of mines and other hazards. Safe return routes are mapped out to ensure that when the community is ready to return to its original land, it can do so without the risk of injury from landmines or unexploded ordnance.

Finally, outreach is conducted to explore options for medical support, including the possibility of receiving assistance from cross-border humanitarian organizations or traditional healers. In many cases, the community must rely on its own resources, but when available, external support is sought to augment local efforts.

One of the key aspects of the CHD framework is its cyclical nature. The phases of Anticipate, React/Evade, and Mitigate are not linear steps but interwoven elements of an ongoing system that adapts to the rhythms of conflict. As armed actors move through the region and violence escalates or subsides, the community continues to adjust, with an emphasis on maintaining health resilience and social cohesion even in the face of extreme challenges.

CHD is implemented through a localized, participatory process rooted in community structures such as village health workshops and committees. Central to its effectiveness is the adaptive integration of existing coping strategies and displacement routines. By building on what communities already do to endure and resist, CHD enhances these grassroots mechanisms through structured health resilience. Through collaborative planning, contextual adaptation, and shared responsibility, CHD transforms health into a sustainable form of civilian resistance that strengthens both individual survival and collective agency in the face of irregular warfare.

Civilian Health Defense Within the Resistance Operating Concept

In irregular warfare, the Resistance Operating Concept (ROC) offers a strategic approach to a whole-of-society resistance model where communities create self-sustaining systems of survival and adaptation. Within this context, CHD aligns with the ROC by using health resilience as a tool for civilian resistance, enabling communities to contest both the physical and psychological impacts of irregular warfare.

The ROC stresses that resistance is most effective when driven at the grassroots level, with local communities taking ownership of their own survival. Similarly, CHD places the responsibility for health-based resistance directly in the hands of communities, allowing them to prepare for and respond to threats without becoming dependent on external actors for survival. CHD empowers local health systems by training communities to anticipate health risks, develop adaptive survival strategies, and manage local healthcare resources independently.

In conflict zones like Myanmar, adversaries often weaponize health insecurity by destroying healthcare infrastructure, blocking humanitarian aid, or attacking medical workers. CHD subverts this tactic by maintaining community-based healthcare systems that are robust enough to function despite external threats. By ensuring continuity of health services, CHD denies adversaries the power to use health as a means of control, diminishing their ability to dominate populations through essential services. CHD offers a robust example of how civilian populations can resist occupation and control through health-based self-defense strategies.

Conclusion

Rooted in grassroots knowledge and collective action, CHD powerfully illustrates how health can function as a critical form of civilian resistance. It highlights how health-based defense can complement traditional resistance methods by preserving social cohesion and disrupting coercive tactics aimed at breaking civilian will.

Editorial Note:

This article is a reader submission. The Resistance Hub presents it to provide insight into individual perspectives from conflict-affected regions and how they have adapted or applied irregular or asymmetric approaches. The views and interpretations in the article belong to the author, and do not represent the position of The Resistance Hub. Publication should not be interpreted as endorsement of any actor, organization, or claim.