The Invisible Foundation of Resistance

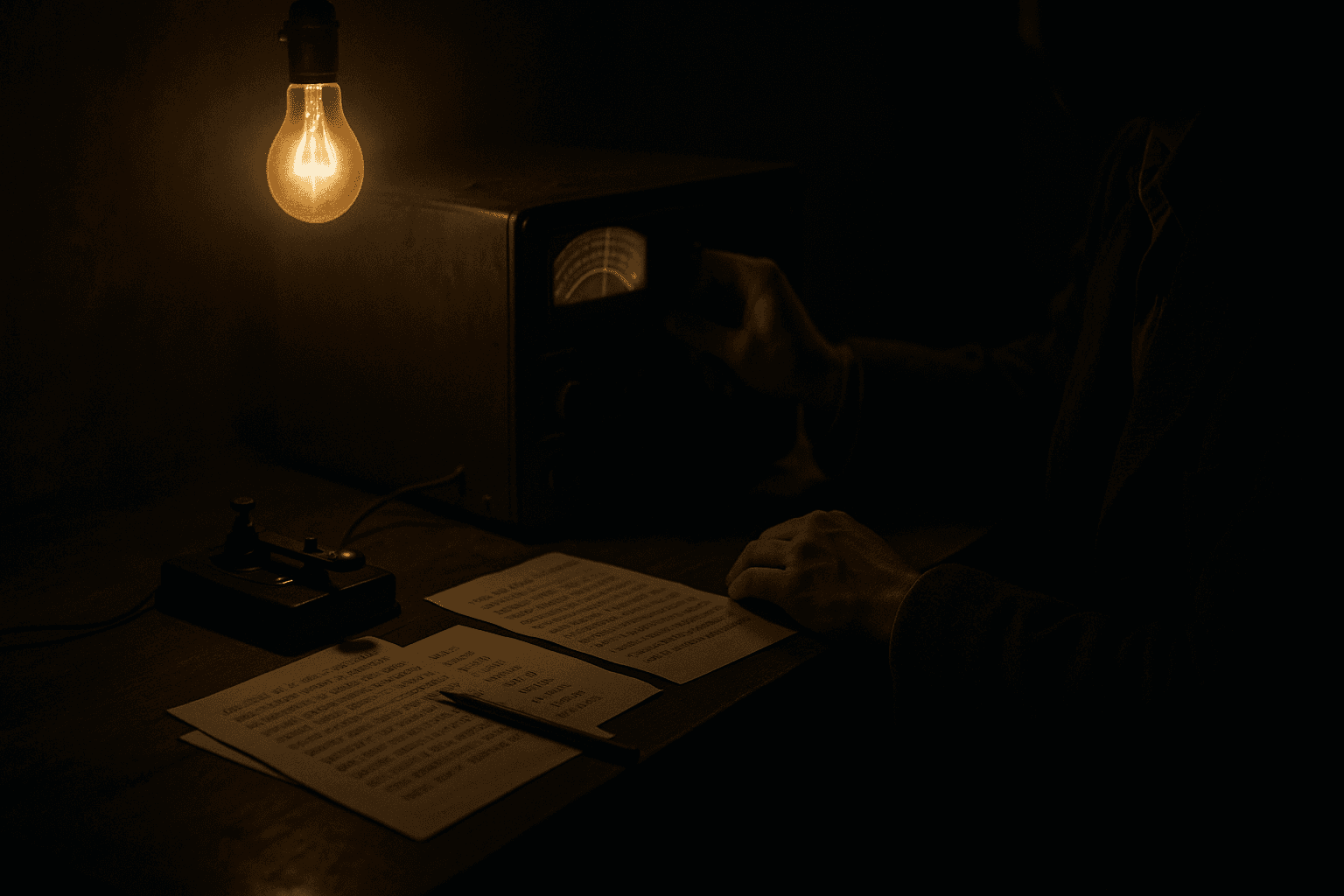

Espionage is the first tool of resistance, the act of gathering, concealing, and transmitting knowledge when discovery means death. In denied territory, where an occupying power controls the instruments of state and surveillance, open defiance is impossible. Underground networks connect isolated cells, protect leadership, and turn awareness into action. Through espionage, resistance movements can move from isolation to coordination.

The Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies (ARIS) series defines the underground as the clandestine element that enables all others to function. Without this hidden structure, guerrilla forces cannot operate, auxiliaries cannot resupply, and political leadership cannot plan or communicate. Espionage is therefore the first manifestation of organized resistance within a denied environment.

Espionage exists to transform denied ground into contested ground and, eventually, controlled territory. Every successful resistance, whether in colonial Algeria, Batista’s Cuba, or Sri Lanka’s Tamil north, began by reclaiming information space from the adversary. Clandestine networks, secure communications, and infiltration of hostile systems were the precursors to liberation.

Espionage is invisible by design, but it shapes every visible outcome of resistance warfare. It is the architecture beneath the surface, the hidden foundation on which open struggle is built.

What Espionage Is — and What It Is Not

Espionage within resistance warfare is a deliberate, long-term act of collection, concealment, and influence. It is not reconnaissance or observation from a distance. It is the slow, deliberate penetration of hostile systems to secure the information that allows a movement to exist.

Definition and Function

Espionage in resistance movements is the organized and clandestine effort to obtain knowledge denied by the enemy. Operatives collect information on troop movements, logistics, collaborators, communication routes, and political intentions. They do this under occupation or authoritarian rule, where exposure is fatal and communications must be invisible. According to Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare, the underground performs four essential functions: intelligence, counterintelligence, communications, and logistics. Espionage sits at the heart of all four. It enables the resistance to see, anticipate, and survive when it lacks territory, manpower, or heavy arms.

Distinction from Reconnaissance

Reconnaissance is tactical. It observes the immediate environment and supports short-term operations in contested areas. Espionage is strategic and enduring. It operates within denied terrain, where enemy control is near total, and builds long-term access to information. Reconnaissance reports what is seen. Espionage ensures that what is seen has meaning and consequence.

Distinction from Counterintelligence

Counterintelligence belongs to controlled terrain, where a movement has sufficient security to defend itself from infiltration. Espionage precedes that phase. It builds the structure that counterintelligence later protects. Without espionage, there is nothing to safeguard; without counterintelligence, espionage cannot survive. Both are sequential, not interchangeable.

The Underground Context

The ARIS framework divides resistance into three components: the underground, the auxiliary, and the public movement. Espionage resides exclusively in the underground. It operates under cover identities, through compartmented cells, and with strict need-to-know separation. It is the mechanism by which the underground links outward to auxiliaries and upward to leadership.

Espionage is therefore the first organized intelligence structure of any resistance movement. It allows the underground to function as the nerve center of the resistance body, silent, unseen, and indispensable.

Why Espionage Is Necessary

Intelligence for Targeting

Espionage identifies what can be struck and when. It provides data on enemy logistics, command nodes, infrastructure, and collaborators. Every act of sabotage, ambush, or subversion relies on prior clandestine reporting. In Algeria, the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) could not have executed coordinated strikes without agents embedded in French colonial institutions feeding constant updates to its Renseignement et Liaisons networks.

Survivability and Continuity

Clandestine intelligence enables a movement to stay alive under pressure. Espionage warns of raids, infiltrations, or policy shifts before they occur. It locates safe houses, tests the loyalty of recruits, and screens potential collaborators. Without this flow of hidden information, resistance networks fracture and die. The ARIS Human Factors study emphasizes that the psychological endurance of underground members depends on the perception that their intelligence work keeps others safe, a tangible sense of purpose that sustains morale.

Detection and Internal Security

Espionage also informs counter-infiltration. Before a movement can practice counterintelligence, it must know who within its environment can be trusted. Early underground operatives are not only collectors; they are observers of behavior, mapping human terrain inside both enemy and friendly systems. This observation becomes the seed of organized internal security once the movement gains ground.

Strategic Leverage

Intelligence provides more than tactical advantage. It creates political leverage. By understanding the adversary’s plans, logistics, and weaknesses, a resistance movement can influence negotiations, frame propaganda, and shape external support. In Cuba, urban intelligence networks within the 26th of July Movement provided Fidel Castro’s leadership with insights into police operations and diplomatic channels, allowing the insurgents to time their public messaging as carefully as their attacks.

Transforming Denied into Contested Terrain

The essential purpose of espionage is transformation. It converts the unknown into the knowable and the inaccessible into the vulnerable. Each clandestine observation, report, or infiltration weakens the adversary’s monopoly on information. Over time, this process erodes control, allowing resistance actors to maneuver, act, and eventually hold ground. Espionage is therefore the first act of liberation, not through violence, but through awareness.

Terrain Framework: Denied, Contested, and Controlled

The effectiveness of espionage depends on the type of terrain in which a resistance operates. Terrain in this context is not physical, it is political, social, and informational. Each stage defines what kind of intelligence activity is possible and what the underground must prioritize.

Denied Terrain

Denied terrain is territory where the adversary’s control is total. Security forces operate freely, communications are monitored, and dissent is punishable by death or imprisonment. In this environment, only espionage can function. Operatives must conceal not only their information but their identities, movements, and intent.

The Undergrounds in Insurgent, Revolutionary, and Resistance Warfare describes the underground as the core element in this stage: a clandestine network that conducts intelligence, sabotage preparation, and psychological defense within enemy-controlled areas.

In denied terrain, espionage aims to observe without exposure. It collects small, consistent fragments of knowledge, names, patrol schedules, supply movements, that accumulate into actionable intelligence. Each report erodes the adversary’s perception of total control.

Contested Terrain

Contested terrain emerges when resistance elements gain limited operational freedom. Small units begin to maneuver, external support becomes possible, and selective strikes can occur. Espionage in this stage supports targeting and coordination. It links the underground’s collection networks with the auxiliary structures that conduct transport, communication, and logistics.

In Cuba, urban intelligence cells inside Batista’s police and military converted denied Havana into contested space. Their reporting enabled guerrilla units in the Sierra Maestra to plan operations based on reliable data from the capital. The combination of clandestine urban intelligence and rural maneuver forced the regime to fight on multiple fronts.

Controlled Terrain

Controlled terrain exists when the resistance holds secure areas, whether through physical control or population dominance. Here, the focus shifts from espionage to counterintelligence. The goal is to prevent infiltration, preserve legitimacy, and stabilize governance. Espionage continues but changes character, it becomes strategic collection beyond the movement’s boundaries, aimed at sustaining control and anticipating external threats.

The ARIS Human Factors study notes that once movements achieve control, psychological cohesion and loyalty maintenance become as critical as secrecy. Intelligence structures evolve from survival mechanisms into institutions of governance.

Integration and Transition

These three terrain types are not static. They overlap and transform. A successful resistance uses espionage to push the boundaries of denied terrain outward, converting it into contested ground, and later consolidating it into controlled space. Each phase demands a different balance of secrecy, communication, and risk.

Espionage is the force that drives these transitions. It is the tool that converts knowledge into freedom of action and transforms clandestine existence into political control.

Case Studies — Espionage in Action

Espionage determines whether a resistance movement survives long enough to fight. It is the decisive factor in how denied ground becomes contested and later controlled. Across history, the most effective resistance movements were those that built deep intelligence networks capable of enduring surveillance, infiltration, and attrition. Three cases from the ARIS series demonstrate how clandestine collection shaped both outcome and legacy.

1. Algeria (1954–1962): The FLN’s Intelligence Revolution

The Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) built one of the most sophisticated underground intelligence systems of the twentieth century. In a country where French security services controlled every administrative level, the FLN established the Service de Renseignement et de Liaisons to collect information on troop movements, informers, and administrative vulnerabilities.

Agents infiltrated police offices, post services, and transport networks, using coded messages and couriers to link rural wilayas with urban centers. These networks turned Algeria’s cities from fully denied spaces into contested ground. They provided early warning of French raids and exposed counterinsurgent operations, allowing FLN commanders to preserve cadres and plan retaliatory strikes.

The French counterintelligence campaign, though brutal and extensive, never fully broke the network. Espionage gave the FLN both survivability and strategic reach. It allowed the organization to synchronize operations across distant provinces and influence international opinion by controlling the narrative of the conflict.

2. Cuba (1953–1959): The 26th of July Movement’s Urban Underground

The Movimiento 26 de Julio (M-26-7) faced a modern surveillance state under Fulgencio Batista. The police and military penetrated nearly every civil institution, making open organization suicidal. In response, M-26-7 created an urban underground to conduct espionage and maintain communication with guerrilla fronts in the Sierra Maestra.

Urban intelligence cells infiltrated government ministries, transportation companies, and the Havana police. Couriers disguised as traders carried reports on troop deployments and supply convoys. Radios and coded transmissions were assembled from civilian parts to maintain clandestine communication between Havana, Santiago, and the mountains.

This network allowed guerrilla leaders to time attacks against government convoys and coordinate propaganda releases that undermined regime confidence. Espionage converted Cuba’s urban core—once a denied zone—into contested terrain that linked the political and military arms of the revolutionARIS Casebook Vol 2 2012 s.

The network’s endurance under repression illustrated that intelligence, not numbers, dictated initiative. The Cuban underground proved that when resistance movements own the information domain, they dictate tempo even without territorial control.

3. Sri Lanka (1976–2009): The LTTE’s Intelligence Empire

The Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) developed espionage into a state function. Its Tiger Organization Security Intelligence Service (TOSIS) operated both internally and externally, integrating human intelligence, signals intercepts, and counterintelligence across decades of conflict.

In the early stages, TOSIS agents infiltrated government posts, police stations, and supply depots. They gathered personnel rosters, movement schedules, and political data that allowed targeted assassinations and ambushes. As the LTTE gained territory, intelligence operations expanded into maritime surveillance and diaspora reporting networks, linking Sri Lanka’s north to sympathetic communities abroad.

Even when the Sri Lankan state intensified its counterintelligence apparatus, TOSIS maintained compartmented structures and redundant communication routes. This intelligence depth allowed the LTTE to preserve leadership continuity and sustain operations long after suffering battlefield reverses.

Espionage was was the framework through which the LTTE exercised governance and controlled population behavior. Its eventual defeat resulted not from intelligence failure but from the exhaustion of safe havens and external support.

Long-Term, Dangerous, Vital — Enduring Lessons

Espionage is the most dangerous and enduring act within resistance warfare. It outlasts campaigns, transcends ideology, and remains vital even when open conflict subsides. Every successful movement, whether in Algeria, Cuba, or Sri Lanka, proved that clandestine intelligence determines survival and eventual control.

Long-Term

Espionage demands patience measured in years. The ARIS studies emphasize that intelligence structures must mature quietly before they can influence the fight. Networks grow through trust, compartmentalization, and redundancy.

In Algeria, early clandestine couriers established communication patterns long before the first coordinated attacks. In Sri Lanka, the LTTE’s intelligence service developed for nearly a decade before large-scale operations began. The persistence of these networks allowed both movements to endure political fragmentation, leadership loss, and shifting battle conditions.

Longevity gives espionage a generational quality. Operatives who began as collectors often evolve into the architects of post-conflict security institutions. Espionage is therefore not only a wartime function but also a foundation for governance.

Dangerous

Espionage is the most lethal profession within a resistance organization. Discovery is synonymous with execution. The Human Factors analysis within the ARIS corpus notes that the constant threat of betrayal and exposure produces sustained psychological strain on underground members.

Operatives live under fabricated identities, isolated from comrades, and often from family. The danger is continuous, a pressure that forges discipline and erodes morale if not balanced by ideological purpose. The death of even a single courier can unravel entire networks. For this reason, resistance movements invest extraordinary effort in vetting, redundancy, and deception. Espionage succeeds only when secrecy is institutionalized.

Vital

Espionage is vital because it precedes all other forms of resistance. It is the act that makes guerrilla warfare possible, sabotage effective, and political mobilization sustainable. A resistance movement without espionage is blind and soon destroyed.

The ARIS framework reinforces this point: every underground begins with intelligence work, not armed struggle. It is the mechanism by which denied ground becomes contested, by which contested ground becomes controlled, and by which control matures into governance.

When movements fail, the absence or collapse of their espionage systems is often the cause. When they succeed, their intelligence architecture becomes the blueprint for the state that follows.

Final Thoughts

Espionage is long-term because resistance must survive beyond battles.

It is dangerous because survival requires deception in plain sight.

It is vital because knowledge is the first and last weapon of freedom.

From the streets of Algiers to the alleys of Havana and the jungles of Jaffna, clandestine intelligence has been the thread connecting all successful resistance movements. The record shows that power begins with awareness, and awareness begins with those willing to risk everything to see clearly in the dark.