In recent months, the German Navy has faced a series of alarming sabotage attempts on its vessels. These incidents have raised significant concerns about maritime security in the region. Sabotage has targeted ships under construction and those already in active service, revealing major gaps in naval protection measures.

Investigations suggest both state and non-state actors may be involved. These groups exploit weaknesses in shipyard security and cyber defense systems. Some attacks appear coordinated, pointing to broader efforts to weaken NATO’s maritime capabilities.

German defense officials have responded by calling for tighter coordination with allies and better counterintelligence. They also recommend investing in sabotage-resistant naval technologies and improving security across all phases of ship deployment.

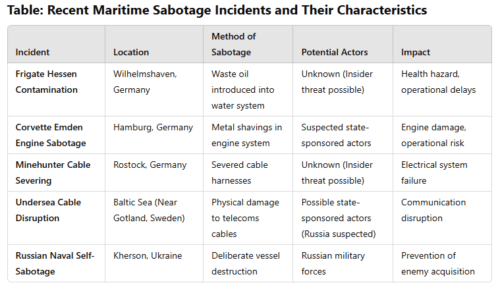

Frigate Hessen Contamination Attempt

In February 2025, while docked at the Wilhelmshaven naval base for scheduled maintenance, the frigate Hessen was the target of a sabotage attempt. Perpetrators sought to contaminate the ship’s potable water system by introducing waste oil into the tanks. Alert personnel detected the contamination early, preventing potential health hazards and operational disruptions. Investigations are ongoing, involving both military and civilian authorities.

Corvette Emden Engine Sabotage

The Emden, a newly constructed corvette awaiting deployment, experienced a serious sabotage incident in early 2025. During a routine inspection at a Hamburg shipyard, several kilograms of metal shavings were discovered in the vessel’s engine system. Had this contamination gone unnoticed, it could have led to catastrophic engine failure during operations. The Hamburg regional prosecutor’s office, alongside local criminal police, is investigating the matter.

Minehunter Cable Severing

Another incident involved a German Navy minehunter stationed in Rostock. Unknown individuals severed multiple cable harnesses aboard the vessel, impairing its operational capabilities. This act of sabotage is under investigation by local authorities, with efforts focused on identifying the perpetrators and their motives.

Broader Maritime Sabotage Context

The recent sabotage attempts against German naval vessels are part of a broader pattern of maritime threats escalating in the Baltic Sea. These incidents underscore the region’s growing vulnerability, where heightened geopolitical tension has made naval infrastructure a key target for hybrid operations.

Hostile actors may aim to disrupt military readiness, test NATO cohesion, or pressure regional governments through targeted acts of sabotage. Attacks on ships—whether under construction or in active service—threaten both national defense and broader alliance security. These threats include physical sabotage, cyber-physical interference, and covert reconnaissance of military ports.

Naval officials have responded by increasing inspections, hardening access controls, and conducting background checks on shipyard personnel and contractors. Baltic states are also expanding maritime domain awareness initiatives, including drone patrols and seabed sensor networks. The goal is to detect and deter hostile activities before they escalate into larger security crises.

As threats evolve, German and allied naval forces recognize that deterrence now requires both traditional defenses and rapid, integrated counter-sabotage capabilities. Without these adaptations, naval operations in the Baltic risk disruption, delay, or degradation—vulnerabilities adversaries are likely to exploit.

Undersea Cable Disruptions

In February 2025, Swedish authorities reported damage to an undersea telecommunications cable near Gotland. This incident is not an isolated occurrence but rather part of a broader trend of disruptions to undersea infrastructure. These cables serve as critical communication lifelines, supporting civilian and military operations, and their compromise poses a significant security risk.

The nature of these disruptions suggests deliberate interference, as accidental damage from fishing activity or natural phenomena is relatively rare. The Baltic region, which hosts extensive undersea fiber-optic networks and military communication links, has become a focal point for suspected sabotage operations. The difficulty in monitoring and securing vast underwater expanses makes these cables highly vulnerable targets for adversaries seeking to disrupt communications and intelligence-sharing among NATO allies.

Russian Naval Sabotage in Kherson

Similar sabotage patterns have been observed in other maritime theaters beyond the Baltic Sea. Reports indicate that Russian troops have deliberately sabotaged their naval vessels in Kherson, either to prevent them from being captured by advancing enemy forces or to avoid direct combat situations. This form of self-sabotage reflects a strategic calculation wherein naval assets are deemed more valuable incapacitated than in enemy hands.

Historical precedents show that self-sabotage has been employed in past conflicts to deny opponents access to critical military resources. In the modern context, these actions reinforce the notion that naval sabotage is not limited to external threats but can also be executed as a deliberate military tactic.

Potential Actors and Motivations

While definitive attribution of the recent German naval sabotage incidents remains complex, several key indicators suggest potential actors and their motivations:

State-Sponsored Espionage and Hybrid Warfare

The sophistication and coordination of these attacks suggest that they are unlikely to be the work of independent actors or rogue elements. Instead, they may be part of a broader strategy that state-sponsored operatives employ to undermine NATO naval readiness. Given the ongoing geopolitical tensions in the region, Russian intelligence and special operations units are considered prime suspects.

Hybrid warfare tactics, which integrate conventional military actions with cyber warfare, psychological operations, and sabotage, have been widely observed in modern conflicts. The pattern of deliberate interference with undersea cables, naval vessels, and strategic maritime infrastructure aligns with past Russian activities aimed at destabilizing Western military operations and exerting pressure on European allies.

Insider Threats and Industrial Sabotage

Another potential vector for these attacks involves insider threats within shipyards and naval bases. The nature of the sabotage—particularly incidents occurring within secured maintenance facilities—raises the possibility that individuals with authorized access have facilitated these operations. Several factors can motivate insider threats, including ideological alignment with adversarial states, coercion through blackmail or financial incentives, or discontent among personnel.

Enhanced security protocols within shipyards, including stricter background checks, increased surveillance, and controlled access to sensitive equipment, are being implemented to mitigate these threats. However, an insider element significantly complicates efforts to prevent future sabotage attempts, requiring continuous vigilance and intelligence cooperation among NATO allies.

So what?

Recent sabotage attempts against German naval ships highlight a wider maritime security problem that crosses national borders. Attacks on undersea cables, self-sabotage in war zones, and spying by state actors show rising risks to navies. These evolving threats place ships and critical systems in danger during both peace and conflict. To counter this, countries must boost security, share intelligence, and build better tools to detect and stop sabotage early.

Historical Parallels

Sabotage in naval contexts has historical precedents:

World War II

Both Allied and Axis forces used sabotage to weaken enemy fleets and delay shipbuilding efforts. The British conducted Operation Source in 1943, using X-class midget submarines to disable German battleships, including the Tirpitz. These operations involved high-risk underwater approaches, explosive charges, and specialized crews trained for covert insertion.

The Axis powers also launched sabotage missions. German agents attempted to disrupt British naval operations by planting explosives in ports or infiltrating supply chains. Italian naval commandos pioneered frogman attacks, using human torpedoes to strike Allied ships in heavily guarded harbors.

Cold War Era

During the Cold War, sabotage took a quieter but equally dangerous form—espionage and covert disruption of naval capabilities. The Soviet Union and the United States both targeted undersea cables, surveillance equipment, and naval shipyards. Intelligence agencies inserted moles and hackers into military-industrial networks to gather information or subtly degrade systems.

In one notable example, U.S. operatives allegedly inserted manipulated software into Soviet systems, causing technical failures without direct confrontation. Similarly, suspected Soviet operatives were linked to port sabotage and equipment tampering in NATO-aligned countries. These actions often blurred the lines between sabotage, subversion, and electronic warfare.

Implications and Countermeasures

The recent sabotage attempts have profound implications for maritime security:

- Operational Readiness: Repeated sabotage can erode naval forces’ operational capabilities, leading to increased maintenance costs and reduced fleet availability.

- Strategic Vulnerabilities: Targeting under-construction vessels and critical infrastructure exposes vulnerabilities that adversaries may exploit to gain strategic advantages.

Enhanced Security Protocols

In response to the recent sabotage incidents, naval forces and shipbuilding facilities are implementing stricter security protocols to mitigate insider threats and external breaches. One key measure involves strengthening access controls within shipyards, naval bases, and maintenance facilities. This includes implementing multi-layered authentication systems, biometric access points, and restricted access zones to ensure only authorized personnel can enter sensitive areas.

Shipyards are significantly increasing surveillance to protect key assets. Security teams are installing advanced CCTV systems with facial recognition and motion detection. These systems actively monitor movements around ships and sensitive equipment to detect suspicious behavior and prevent sabotage. Security patrols have also been intensified, with random inspections and increased presence of armed security personnel to deter potential saboteurs.

Another crucial aspect of enhanced security involves conducting thorough background checks and continuous vetting of personnel working on naval vessels and military projects. Governments and military agencies are reinforcing their vetting procedures by collaborating with intelligence agencies to screen employees, contractors, and subcontractors for potential security risks. Regular security audits and psychological assessments are also introduced to detect any anomalies indicating insider threats.

International Collaboration

Given the transnational nature of maritime threats, NATO allies and partners have prioritized deeper security collaboration. They are refining intelligence-sharing systems to deliver real-time alerts on sabotage threats and emerging malicious activity patterns. NATO and European defense institutions are developing a centralized maritime threat database. This system helps member states detect and respond to sabotage attempts quickly.

Joint naval exercises now include expanded counter-sabotage training. These drills simulate real-time scenarios where forces must detect and neutralize sabotage threats immediately. The exercises also improve coordination between navies, coast guards, and intelligence agencies. Cybersecurity cooperation is increasing as well, focusing on defending ship systems from cyber-physical attacks.

Another area of collaboration is rapid response team development. These teams specialize in counter-sabotage and deploy quickly to affected maritime sites. They include maritime security, cyber defense, and counterintelligence experts. Once deployed, they conduct forensic investigations and implement countermeasures in partnership with host nations.

Technological Investments

Investments in cutting-edge technology are critical for countering maritime sabotage. One major focus is underwater monitoring systems. Naval forces now deploy autonomous underwater drones with sonar and AI-driven anomaly detection. These drones patrol harbors and shipyards, scanning for sabotage attempts like explosive devices or tampering with ship hulls.

Navies are also integrating sensor networks across critical maritime infrastructure for real-time threat detection and response. These sensors include hydrophones to detect unusual underwater sounds and infrared cameras to track nighttime ship movements. Electronic warfare systems provide protection against cyber threats targeting communications or control systems.

Another breakthrough involves predictive analytics and machine learning models that identify sabotage risks before they occur. These systems analyze past sabotage attempts, geopolitical tensions, and insider threat indicators. They then issue early warnings to naval commanders and security teams for proactive action.

Finally, shipbuilders are enhancing vessel designs to resist sabotage. New warships feature redundant systems, tamper-proof controls, and built-in diagnostic tools. These features reduce vulnerability and help isolate damage quickly. Even if an attack happens, these safeguards preserve core functions and mission readiness.

Conclusion

The recent wave of sabotage incidents targeting the German Navy underscores the evolving nature of threats in the maritime domain. To counteract these challenges, naval forces and defense organizations adopt a multi-pronged approach emphasizing enhanced security protocols, international collaboration, and technological advancements. By implementing these measures, nations can better safeguard their naval assets, critical infrastructure, and strategic capabilities against future sabotage attempts.

Sources

- “German Navy Thwarts Another Sabotage Attempt,” The Maritime Executive, February 23, 2025. maritime-executive.com

- “Germany Investigates Suspected Sabotage of New Warship,” The Defense Post, February 12, 2025. the defense post.com

- “Unknown Saboteurs Are Targeting German Navy Warships,” The Maritime Executive, February 18, 2025. maritime-executive.com

- “Sweden Investigates Suspected Sabotage of Baltic Sea Telecoms Cable,” Reuters, February 21, 2025. reuters.com

- “Russia’s War Beneath the Waves Threatens Us All,” The Times, February 3, 2025. thetimes.co.uk