The Fear That Governs Action

Nuclear weapons define the outer boundary of great-power conflict, but it is not the warhead that decides whether a fighter jet is shot down or a convoy is struck. It is a matter of political will, the readiness of leaders, parliaments, and alliances to bear the risks of escalation. Capabilities set the stage, but choices decide the script.

Each of the cases explored here was shaped by its own geography, timing, and political constraints. Decisions made by states and alliances were taken in real time, often under pressure and with incomplete information. The aim is not to second-guess those choices or criticize the actors involved, but to draw lessons from how political will, or restraint, operated in flashpoints of great-power competition.

A century of deterrence theory has focused on arsenals and force ratios. The examples of Turkey, Estonia, Poland, Romania, Syria, Crimea, and Ukraine suggest that the decisive variable is often the willingness to act, or the decision to withhold action, against nuclear-armed states.

Case One: Turkey’s Instant Decision, 2015

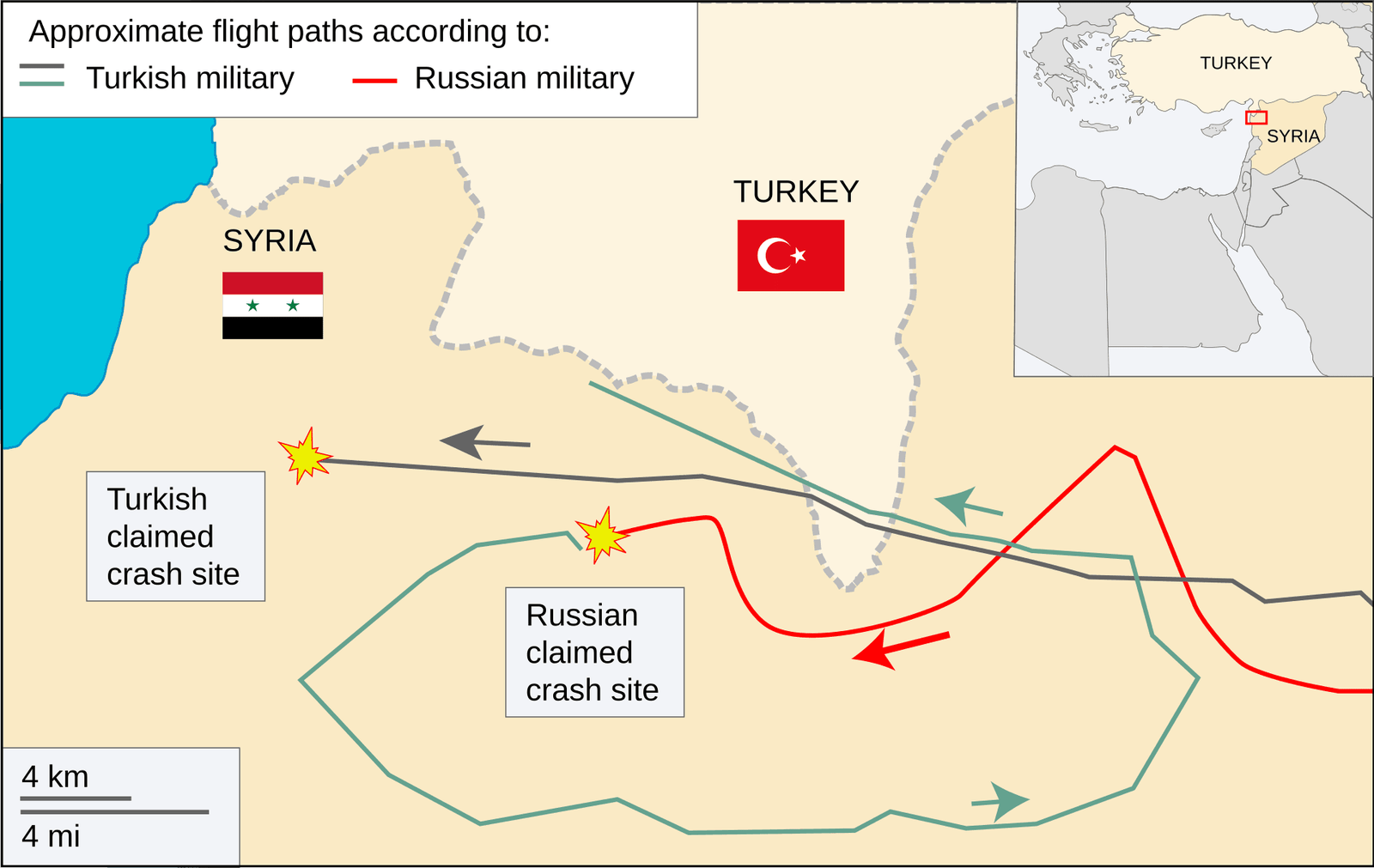

On 24 November 2015, a Russian Su-24 crossed briefly into Turkish airspace near the Syrian border. The violation lasted seconds, but Ankara had already issued multiple warnings that its sovereignty would be enforced. A Turkish F-16 fired an air-to-air missile, downing the intruder.

The military outcome was straightforward; the political meaning was not. Turkey acted alone, fully aware that Moscow might choose to escalate. There was no NATO council vote, no time for an alliance consensus round, and no guarantee that partners would back Ankara if events spiraled. The decision was sovereign, immediate, and highly visible, not just to Russia but to every state watching how far a NATO member would go to defend its airspace.

Moscow’s reaction underscored the stakes. Furious rhetoric, sanctions on Turkish goods, and suspended tourism links followed, yet Russia stopped short of military retaliation. In effect, both sides demonstrated limits: Turkey showed it would enforce a red line even against a nuclear-armed adversary, while Russia signaled that the loss of an aircraft did not justify escalation into open conflict. The shoot-down thus became a defining case study in unilateral willpower: an individual state imposing its boundary without waiting for allied cover.

Case Two: Estonia’s Long Incursion, 2025

Fast forward to September 2025. Estonia reported that three Russian MiG-31 fighters penetrated its airspace and remained for roughly twelve minutes, an unusually long violation by any standard. NATO’s Baltic Air Policing mission scrambled jets to intercept, shadowing the intruders until they turned back. Yet the encounter ended without shots being fired. The official response unfolded in diplomatic channels: condemnations in Brussels, consultations among allies, and a complaint lodged at the United Nations.

The difference from Turkey a decade earlier is structural. Estonia’s skies are not defended solely by its own small air force but by NATO’s rotational policing mission, which rotates Allied fighters through Ämari Air Base and Šiauliai in Lithuania. That arrangement ensures deterrence through visible presence, but it also distributes responsibility. A missile launch over Narva would not be Estonia’s decision alone; it would implicate Washington, Berlin, Paris, Warsaw, and thirty allied capitals at once. The decision loop is therefore slower, more cautious, and designed to avoid accidental war.

This dynamic captures the paradox of alliance defense. Collective deterrence is NATO’s strength; an attack on one is an attack on all. Yet that same collective structure can create hesitation at the tactical edge, where decisions must be weighed not only for local effect but for their potential to trigger a crisis across the alliance.

The State–Alliance Divide

The juxtaposition reveals a crucial nuance: political will is distributed differently in sovereign states and in alliances.

Unilateral will, as demonstrated by Turkey in 2015, is fast, decisive, and inherently risky. A single government can set a red line and act on it in seconds, bearing the consequences alone.

Collective will, by contrast, as seen in NATO’s response over Estonia in 2025, is cautious, layered, and often restrained. Decisions are filtered through multiple capitals, each with its own domestic politics and tolerance for risk.

For adversaries testing borders, the difference plays out in real terms, not theory. In 2015, a Russian pilot crossed into Turkish airspace and Turkey shot his plane down within moments. In 2025, a Russian pilot lingered over Estonia and NATO jets intercepted him, but the response stopped at protests and alliance talks. The contrast is clear: when states act alone, they can enforce red lines instantly; when alliances respond, they move slower, share the risk of escalation, and often hesitate at the tactical edge.

Poland, Romania, and the Air Policing Frontier

The tension between unilateral and alliance will was visible again this September. On the night of 9–10 September 2025, nearly two dozen Shahed drones crossed into Polish airspace. Polish fighters engaged, downing several; debris recovered from others revealed no explosives, only unarmed “dud” airframes. Warsaw’s foreign minister described the event bluntly as a Kremlin test, a probe to measure NATO’s reactions without risking direct escalation.

Romania faced similar incursions days later, reporting a Russian drone that loitered for nearly fifty minutes inside its territory. Romanian F-16s considered engagement but ultimately held fire, and Bucharest sought NATO consultations instead. The contrast was striking. Poland signaled a readiness to shoot, projecting immediate resolve; Romania emphasized allied coordination and restraint, signaling that any escalation would be handled through NATO’s collective structures. Both choices were political acts, but they revealed different calibrations of risk along the alliance’s eastern flank.

Could NATO go further by extending air policing missions deeper, perhaps toward contested corridors like the Dnieper? Operationally, it is feasible, allied squadrons already sustain the Baltic mission on rotation. Politically, such a step would be transformative: shifting from defending allied skies to shadowing Russian frontiers. That would not only deter further violations but also test whether NATO’s collective will can ever match the speed and clarity of unilateral national decisions made in real time.

Proxies and Deniability: Wagner at Khasham

Airspace is not the only testing ground. On 7 February 2018, U.S. special operations forces and their Syrian Democratic Force partners near Khasham came under a coordinated assault by pro-regime fighters, including Russian private military contractors from the Wagner Group. The attackers advanced with armor, artillery, and infantry, seemingly probing whether the U.S. would stand its ground. Washington’s response was overwhelming: artillery batteries opened fire, an AC-130 gunship pounded the assault columns, F-15Es struck from above, and armed drones harassed retreating units. Within hours, the attackers were decimated, with estimates of casualties in the hundreds.

Here again, political will proved decisive. The U.S. command authorized massive firepower despite the risk that Russians might be among the casualties. Moscow, choosing to preserve plausible deniability, disavowed responsibility and downplayed the loss of Wagner personnel. The battle underscored a clear lesson: when political will is concentrated, immediate, and decisive, even ambiguous engagements, thick with deniability and uncertainty, can be resolved overwhelmingly in favor of the side willing to act.

The Foil: Crimea, 2014

Yet the same Wagner model succeeded when political will was absent. In early 2014, “little green men”, unmarked Russian soldiers, contractors, and local auxiliaries, fanned out across Crimea. They seized the regional parliament, blocked Ukrainian bases, took over airports, and secured communications hubs. The operation was fast, coordinated, and deliberately cloaked in ambiguity. Kyiv, already reeling from political upheaval after the Maidan protests and uncertain about the scale of Russia’s commitment, hesitated to confront the intruders directly. NATO and the EU issued condemnations and imposed sanctions, but neither intervened militarily. Within weeks, a referendum was staged under Russian control, and Crimea was annexed.

The tactical difference between Khasham in 2018 and Crimea in 2014 was negligible: in both cases, lightly armed irregulars or contractors probed to see how far they could advance. The political difference was decisive. In Syria, Washington authorized an overwhelming force to defend its position. In Crimea, Kyiv’s hesitation and the West’s reluctance to escalate allowed Russia to convert a gray-zone operation into a strategic fait accompli. Where political will is absent, even modest probes can snowball into permanent territorial gains.

Threats and Signals: Syria’s Chemical Weapons Line

Another instructive episode came in April 2018, when the United States, Britain, and France prepared coordinated strikes on Syrian regime facilities tied to chemical weapons production and storage. In the days before the operation, Moscow issued stark public warnings: any aircraft or naval platform launching ordnance against Syrian territory would be targeted in return. The language suggested Russia might be willing to escalate directly against NATO militaries.

When the strikes came, allied cruise missiles and aircraft hit multiple targets around Damascus and Homs. Russian air defenses tracked the salvos but did not engage the launch platforms. No allied ships or aircraft were fired upon. The gap between Moscow’s rhetoric and its actions was glaring.

The lesson is stark. Verbal threats are not political will. Credibility rests not on words but on decisions made under pressure. In this case, Russia calculated that firing on U.S., British, or French forces risked an uncontrollable escalation that outweighed the value of defending Syrian facilities. Political will, or its absence, again defined the outcome. Ultimately, a threat without follow-through is capability plus intent untested; only action confirms whether will is real.

Ukraine: Will as a Force Multiplier

The ongoing war in Ukraine illustrates the principle most clearly. On paper, Russia retains clear numerical advantages in tanks, artillery, aircraft, and missile stockpiles. Yet Ukraine has endured, adapted, and in places regained ground, powered not only by battlefield ingenuity but by sustained political will in Kyiv and across Western capitals. Decisions to supply advanced air defenses, long-range artillery, precision drones, and intelligence support gradually narrowed the gap between asymmetrical forces.

For Ukraine, willpower has acted as both shield and sword. At home, it sustained mass mobilization and national resilience under relentless bombardment. Abroad, it convinced allies to accept economic costs, navigate domestic divisions, and commit military resources that offset Russia’s numerical advantage. What might otherwise have been a rapid collapse became a drawn-out contest in which political will redefined the balance.

Here, will is not a backdrop but the decisive capability that enables resistance. It multiplies limited force, sustains coalitions, and denies Moscow the easy victory it expected. In Ukraine, political will has proven to be the fulcrum on which great-power strategy turns.

The Nuclear Threat and the Will to Act

Across these cases lies a recurring dilemma: how far can states or alliances go in enforcing sovereignty and punishing violations without sparking escalation?Nuclear deterrence filters every decision and magnifies the consequences of even small-scale encounters. Shoot too quickly, and a tactical enforcement action could spiral into a crisis no one intended. Hold fire too long, and the absence of response risks normalizing violations, inviting more ambitious probing in the future. This tension places leaders and commanders in an unforgiving space where both action and inaction carry strategic costs.

Political will is therefore both a shield and a trap. When exercised firmly, it can restore credibility, impose boundaries, and deter further challenges. Yet the same restraint that avoids escalation can also embolden adversaries who interpret caution as weakness.Leaders balance two competing fears: triggering nuclear confrontation on one side and allowing deterrence to erode on the other. The dilemma is not simply military but political, a test of judgment under uncertainty, where credibility, alliance cohesion, and national survival are all on the line.

Policy Implications: Making Will Credible

If political will is the decisive capability, what makes it credible? Several measures stand out:

- Clarify Rules of Engagement. Ambiguity at the tactical edge encourages probing. Publishing clearer thresholds — as Turkey did — can raise the cost of violations.

- Delegate Authority in Alliances. NATO’s air policing missions should empower commanders with defined kinetic options, narrowing the gap between decision and action.

- Pair Restraint with Punishment. If kinetic action is withheld, political costs should be immediate: sanctions, public exposure, and rapid alliance statements.

- Deny Deniability. Treat proxy or “unmarked” forces as extensions of state power unless conclusively proven otherwise. Crimea showed the cost of looking away.

- Sustain Long-Term Will. As Ukraine demonstrates, enduring resistance depends on political choices repeated month after month. Capabilities decay without will.

Will as the Ultimate Capability

Great-power competition is not only a contest of weapons but a contest of nerve. From Turkish F-16s to Estonian interceptors, from Wagner mercenaries to Ukrainian brigades, the decisive variable has been political will, the readiness to act under risk. Capabilities matter. But without will, they remain parked on tarmacs and hidden in arsenals.

The paradox is that will cannot be stockpiled. It must be exercised, demonstrated, and renewed. For NATO, Ukraine, and other actors facing a nuclear adversary, the challenge is to align political resolve with military capacity, so that resistance is not just a word, but a credible, practiced reality.

At the same time, these cases are imperfect illustrations. Each incident involved its own geography, timing, domestic politics, and alliance dynamics. The calculus is both complex and complicated, with no single template for action. This analysis does not seek to pass judgment on decisions made in moments of danger, but rather to draw lessons from flashpoints where political will, or its absence, shaped outcomes in great-power competition.

Sources

- BBC News. “Turkey Shoots Down Russian Warplane on Syria Border.” November 24, 2015. https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/czrp6p5mj3zo

- Wikipedia. “2015 Russian Sukhoi Su-24 Shootdown.” Last modified 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2015_Russian_Sukhoi_Su-24_shootdown

- The Guardian. “Russian Drone Incursion into Poland ‘Was Kremlin Test on NATO.’” September 14, 2025. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2025/sep/14/russian-drone-incursion-poland-nato-ukraine-europe

- New York Times. “How a 4-Hour Battle Between Russian Mercenaries and U.S. Commandos Unfolded in Syria.” May 24, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/05/24/world/middleeast/american-commandos-russian-mercenaries-syria.html

- CNN. “Ukraine Crisis: Timeline of Major Events.” March 22, 2014. https://www.cnn.com/2014/03/22/world/europe/ukraine-crisis

- BBC News. “Syria War: US, UK and France Launch Air Strikes.” April 14, 2018. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-43769332

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply