About the Author:

Moe Gyo is a writer and consultant working with various ethnic organizations in Myanmar. He writes from the Thai–Myanmar borderlands, drawing on years of direct engagement with communities navigating conflict, displacement, and disrupted health systems. His work reflects firsthand observation of how resilience and informal support networks emerge in areas affected by irregular warfare.

This article is a reader-contributed submission to The Resistance Hub.

Part I: The War Marketplace Framework

War as Competitive Governance, Not Just Violence

War is commonly framed as a contest of arms, ideology, or political will. In practice, especially in irregular conflict, wars persist because actors compete to govern. Firepower matters, but it is rarely decisive on its own. What determines endurance and outcome is who can provide order, justice, security, and meaning, and compel or earn civilian compliance over time.

In insurgent environments, the decisive terrain is institutional rather than geographic. Insurgencies survive not because they fight well, but because they outcompete the state in governance. They do not merely resist authority; they replace it. Armed groups tax, adjudicate disputes, regulate markets, enforce norms, and construct narratives of legitimacy. The state, in turn, attempts to defend its monopoly over these same functions. The central struggle in war is therefore not over violence itself, but over authority.

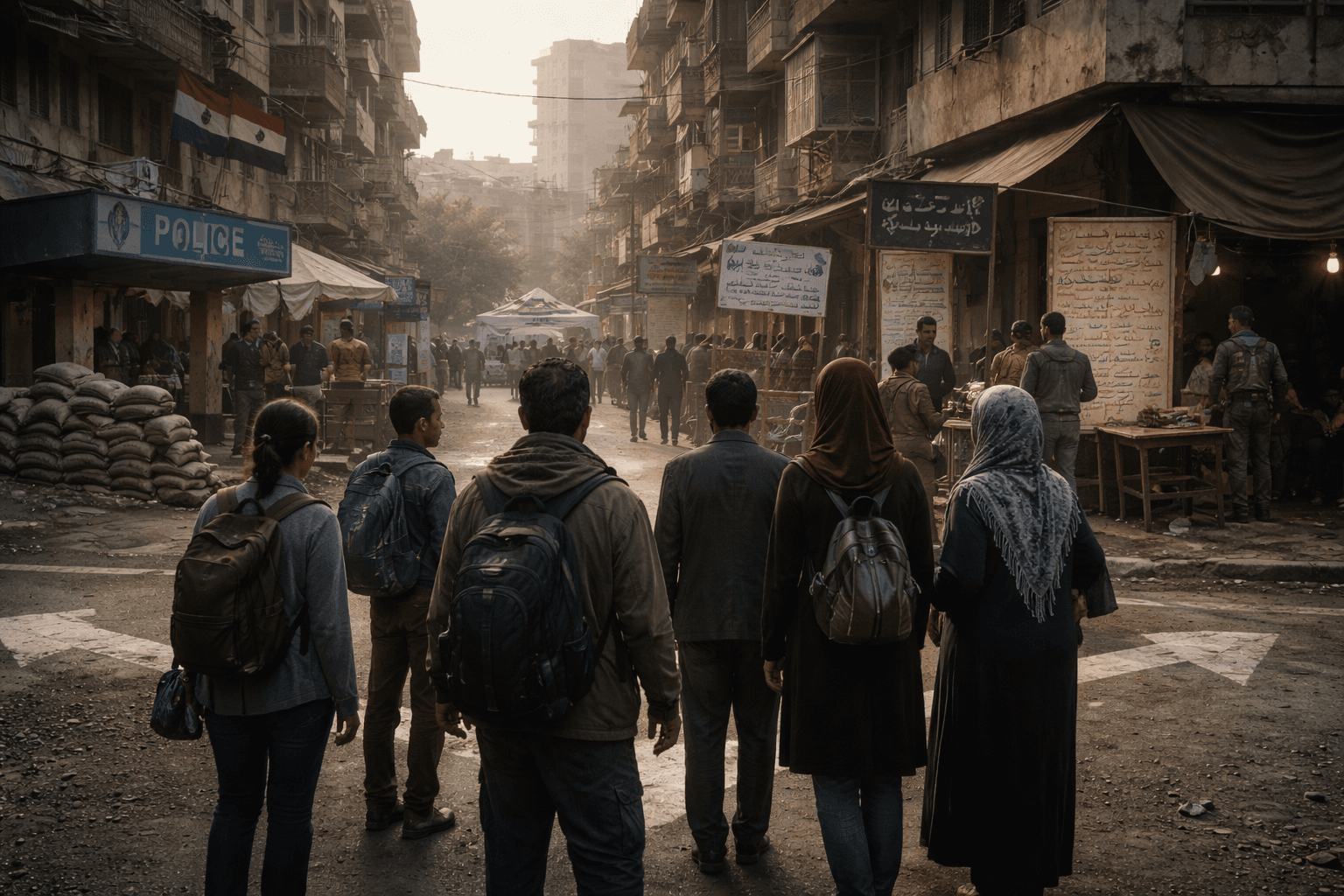

This paper advances the War Marketplace Framework (WMF): a conceptual model that treats insurgency as competitive governance provision under conditions of institutional failure. States and insurgents function as rival providers in a contested marketplace where civilians are not spectators but constrained consumers. Civilians allocate compliance through everyday behavior, paying taxes, obeying rules, sharing intelligence, or withholding cooperation, based on their assessment of relative governance performance under risk and coercion. The side that delivers governance more credibly, predictably, and meaningfully captures compliance, resources, and legitimacy, and ultimately prevails.

Insurgency, in this framework, is not fundamentally about violence. It is about market entry into degraded governance space. Where the state undersupplies security, justice, public goods, or legitimacy, challengers emerge as alternative providers. Violence functions less as an end in itself than as a mechanism for shaping incentives, enforcing authority, and disciplining competition within this marketplace.

Crucially, governance competition does not occur on a blank slate. It is shaped by durable structural conditions that determine how easily new challengers emerge, how civilians can respond, how long organizations endure, and how authority fragments or consolidates. These conditions generate recurring patterns across conflicts, independent of ideology, leadership quality, or battlefield performance. Strategic actors are not merely constrained by this structure; they attempt, often unsuccessfully, to reshape it in their favor.

The argument proceeds in three parts. Part I establishes insurgency as a form of competitive governance and introduces the War Marketplace Framework. Part II—The Market Forces of War analyzes the structural forces that shape competition within this marketplace and explain why certain conflict equilibria recur. Part III—Strategy in the War Marketplace examines how states and insurgents pursue strategy by attempting to manipulate these forces and why many well-intentioned interventions systematically fail.

What the War Marketplace Framework Explains Better Than Existing Models

Existing approaches to insurgency, whether focused on battlefield dominance, ideological commitment, or service provision, capture important elements of irregular war but often fail to explain several persistent empirical puzzles. The WMF addresses these gaps by modeling insurgency as competitive governance provision under conditions of institutional failure.

Why Militarily Weak Insurgents Outlast Strong States

Conventional military models assume that disparities in firepower, manpower, and resources should translate into decisive outcomes. The WMF explains insurgent endurance by shifting the unit of analysis from force ratios to comparative governance performance. Insurgents persist not because they defeat state forces tactically, but because they offer governance that is locally superior, more predictable, or less predatory than that of the incumbent state. As long as insurgents retain sufficient market share in civilian compliance, superior state firepower cannot produce strategic victory.

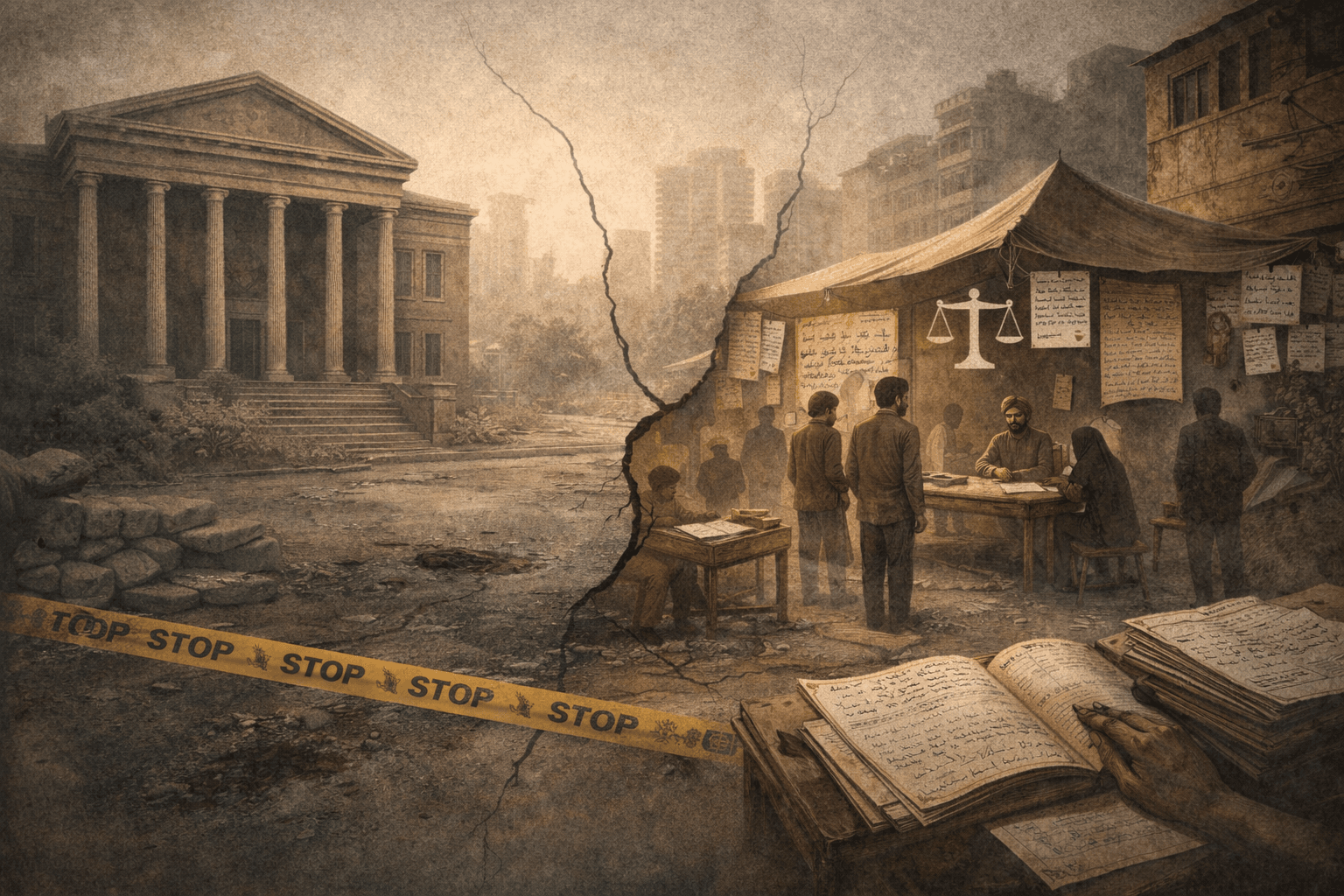

Why Governance Reforms Without Coercive Credibility Fail

Development- and governance-centric approaches often assume that improved service delivery will generate legitimacy and compliance. The WMF explains why such reforms frequently fail when they are not paired with credible enforcement. Governance is a composite good in which security and justice anchor the value of all other services. When the state cannot enforce rules or protect beneficiaries, civilians discount reforms as temporary or symbolic and continue to hedge by complying with insurgents who retain coercive capacity. Legitimacy, in this framework, is inseparable from enforcement.

Why Violence Sometimes Increases Compliance and Sometimes Collapses It

Traditional models treat violence either as a blunt instrument of coercion or as counterproductive repression. The WMF explains this variation by conceptualizing violence as both price and signal within a competitive marketplace. Targeted, disciplined violence signals enforcement capacity and raises the cost of defection, thereby increasing compliance. Indiscriminate or excessive violence, however, degrades governance quality, erodes trust, and increases civilian churn toward alternative providers. Violence succeeds or fails not by its intensity, but by its effect on comparative governance credibility.

Why Negotiated Coexistence Often Emerges Instead of Decisive Victory

Binary models of war termination struggle to explain why conflicts frequently settle into stalemates, power-sharing arrangements, or tacit coexistence. The WMF accounts for these outcomes by identifying equilibrium conditions in which no actor can decisively outcompete rivals across all governance domains. In such environments, duopolies, cartelization, or partitioned control emerge as stable market outcomes rather than temporary failures. Negotiation becomes a rational response to competitive saturation, not a deviation from war logic.

What Is Being Contested: The Governance Product

In the WMF, governance is treated as a composite product, not an abstraction. It consists of four interdependent components:

- Security: Protection from violence, predation, and uncertainty

- Justice: Dispute resolution, rule enforcement, and arbitration

- Public Goods: Infrastructure, welfare, access to markets, and regulation

- Legitimacy: Moral, ideological, or identity-based justification for authority

These components are partially substitutable. Civilians do not require optimal governance; they require adequate, predictable, and fair governance relative to available alternatives. Whether these governance goods generate authority depends not on their intrinsic quality alone, but on how civilians, operating under risk and coercion, evaluate and respond to them.

Civilians as Consumers Under Constraint

Populations in conflict zones are not ideologues or hostages by default. They are risk managers operating under coercion and uncertainty. Civilians “purchase” governance through behavior:

- Paying taxes or extortion

- Complying with rules

- Providing or withholding intelligence

- Participating in institutions or armed groups

- Granting legitimacy or passive acquiescence

These choices are bounded and reversible. Civilians hedge, dual-comply, or shift allegiance as conditions change. Market share is fluid. Understanding how these choices aggregate into authority requires examining the incumbent provider in this marketplace.

The State: Incumbent Monopoly with Structural Weakness

States enter the war marketplace as incumbent monopolies. They control:

- Formal coercive power

- Legal and fiscal authority

- Infrastructure and service networks

- Dominant legitimacy narratives

But in practice, the state is rarely unitary. It behaves more like a fragmented conglomerate of ministries, security forces, political elites, and local brokers with misaligned incentives.

Corruption, repression, and predation are not anomalies; they are competitive failures driven by principal–agent problems. From the civilian perspective, “the state” often appears as a patchwork of competing authorities, some predatory and some absent.

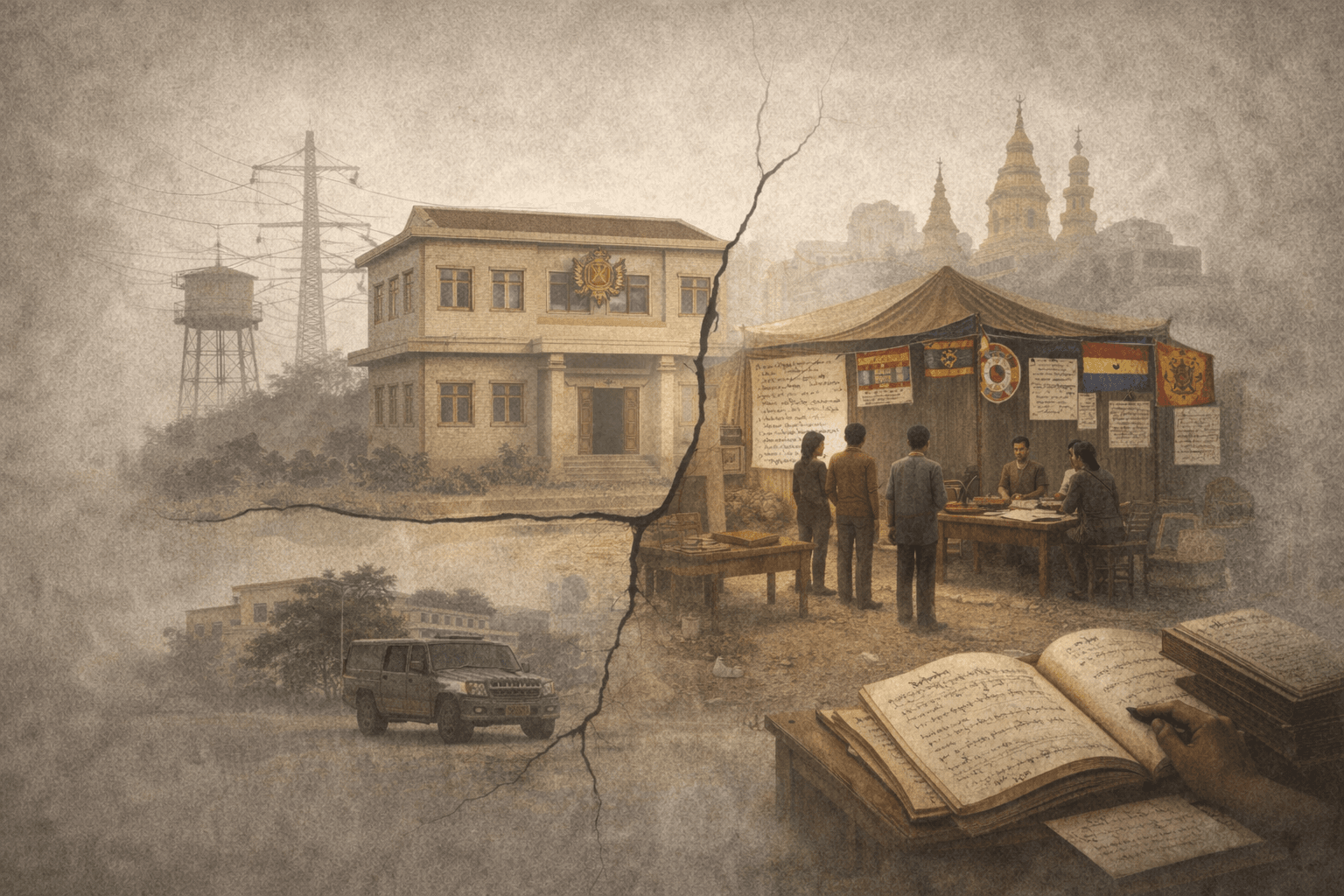

Insurgents enter this environment not as rebels alone, but as competitive firms exploiting governance gaps the incumbent cannot close.

Insurgents as Disruptive Entrants

Insurgent groups enter the governance marketplace like startups targeting a stagnant monopoly. Their advantages are not scale but adaptability and local fit.

They compete by offering:

- Security where the state cannot reach

- Faster, cheaper, or culturally resonant justice

- Protection against corruption and abuse

- Identity, honor, and moral purpose

- Parallel economic and regulatory systems

They operate with low overhead, decentralized command, and rapid feedback loops.

The Insurgent Value Proposition

Successful insurgents bundle violence within a broader governance offering.

1. Ideological Branding

- Emotionally charged narratives

- Clear identity boundaries

- Moral justification for sacrifice and violence

This functions like a high-differentiation brand that lowers recruitment and compliance costs.

2. Alternative Service Delivery

- Local courts

- Protection rackets framed as security

- Welfare, redistribution, and market regulation

Insurgents do not need to outperform the state universally, only locally and comparatively.

3. Competitive Pricing

Civilians pay through:

- Taxes or extortion

- Compliance and loyalty

- Labor, intelligence, participation

Insurgents must offer either

- Lower costs of compliance, or

- Higher value at equivalent cost

Market Share in War

Victory is not measured solely by body counts or terrain seized. Market share matters across four domains:

- Population Control: Compliance, support, and participation

- Territorial Control: Ability to regulate movement and access

- Resource Control: Revenue, logistics, and materiel

- Narrative Control: Moral authority and symbolic dominance

These reinforce one another. Gains in one domain compound gains in others.

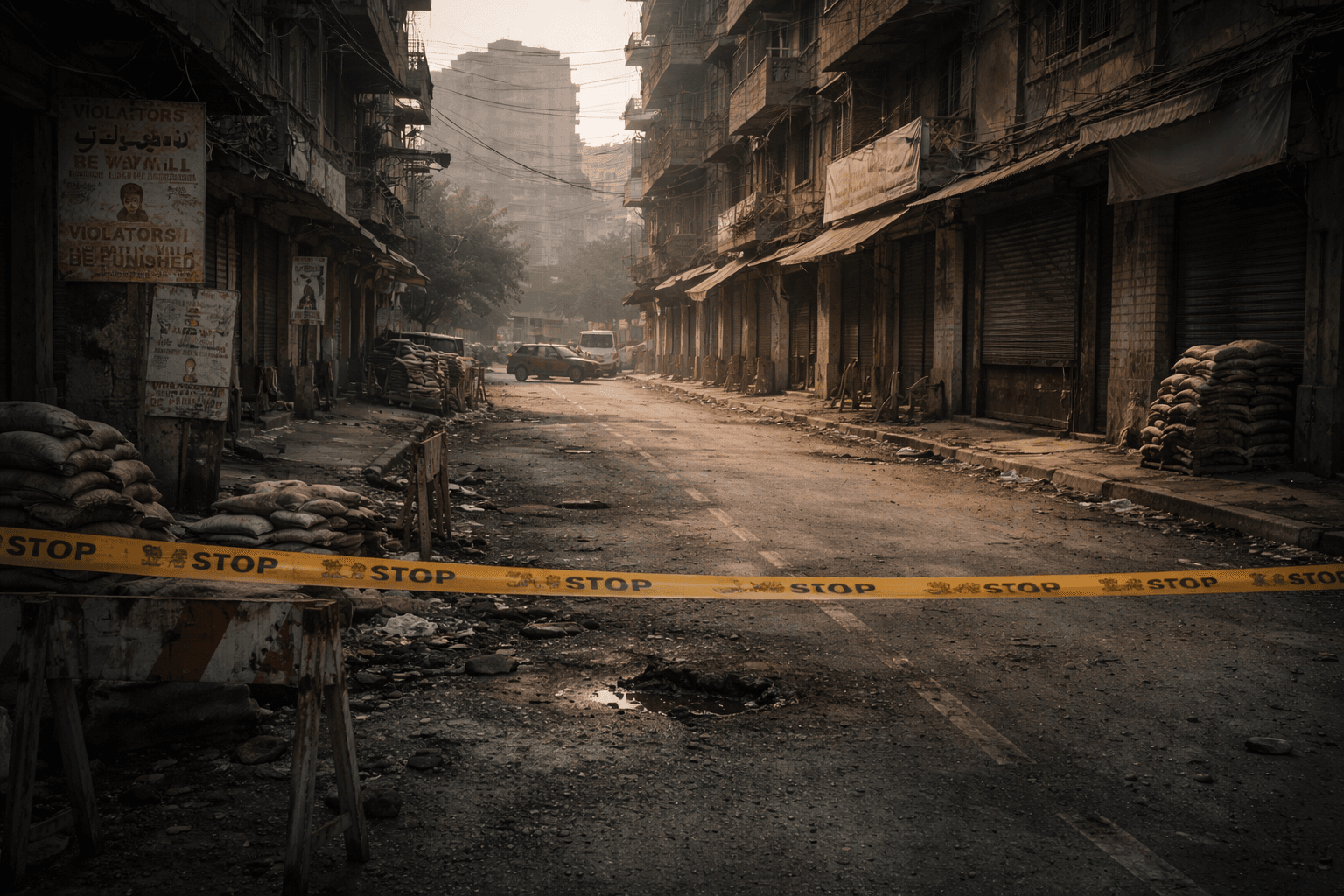

Violence as Price and Signal

Within the WMF, violence serves two functions:

- Price: Raises the cost of supporting competitors

- Signal: Demonstrates enforcement capacity and resolve

Targeted violence can shift behavior. Indiscriminate violence destroys trust and increases churn.

Non-Instrumental Motivations: Honor, Revenge, Identity

Not all behavior is rational in the economic sense. Honor, humiliation, revenge, and sacred values shape preferences and tolerances.

These motivations:

- Reduce sensitivity to governance quality

- Shift legitimacy from performance to symbolism

- Sustain compliance despite high costs

This does not negate market logic: it distorts demand. Insurgents built around revenge or honor prioritize punishment and boundary enforcement over administration, producing expressive rather than instrumental governance.

Competitive Outcomes in the War Marketplace

Different equilibria emerge:

- Monopoly Restoration: State reforms governance and enforces dominance

- Duopoly/Oligopoly: Shared or partitioned control

- Fragmentation: Warlordism and micro-competitors

- Market Takeover: Insurgents become the new state

- Cartelization: Tacit coexistence and negotiated order

Predatory and genocidal conflicts represent market collapse, where authority is pursued through elimination rather than incorporation.

Conclusion: From Competition to Strategy

If war is a competition over governance rather than a contest of destruction, then prevailing requires more than superior force or improved service delivery. It requires deliberately outcompeting rival authorities across the full spectrum of governance functions. This shifts the strategic problem from how to defeat armed opponents to how to eliminate alternative governance markets.

For states, this implies a fundamental reorientation of strategy. Success cannot be achieved solely by killing insurgents, expanding development programs, or conducting episodic reforms. Strategic actors must identify which governance functions insurgents currently provide, why civilians prefer or tolerate them, and how state actions alter the relative costs and credibility of compliance. Force must be employed not to maximize attrition but to enforce institutional dominance, protecting state courts, tax systems, local administrators, and civilian participants while dismantling insurgent governance infrastructure.

Equally, governance reforms that are not coercively protected are strategically inert. Service provision without enforcement signals weakness, invites hedging behavior, and preserves demand for insurgent alternatives. Effective strategy therefore requires sequencing: coercive credibility must anchor reform, and reform must consolidate the gains produced by coercion. Legitimacy follows institutional control; it does not precede it.

These requirements pose a different diagnostic challenge than traditional counterinsurgency models. Rather than asking where insurgents are strongest militarily, strategic actors must ask where they hold governance market share, which civilian segments are hedging, and which institutions, formal or informal, mediate compliance. Victory depends not on clearing territory but on collapsing rival governance supply while monopolizing demand.

Part II—The Market Forces of War applies this framework to strategy, examining how states and insurgents attempt to manipulate governance markets through force, reform, and negotiation, and why most fail to achieve durable monopoly control.

Editorial Note:

This article is a reader-submitted contribution. The Resistance Hub publishes it to present individual analytical perspectives informed by experience in conflict-affected regions, including how irregular or asymmetric approaches are understood and adapted in practice. The views and interpretations expressed are solely those of the author and do not represent the positions of The Resistance Hub. Publication does not imply endorsement of any actor, organization, or specific claim.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply