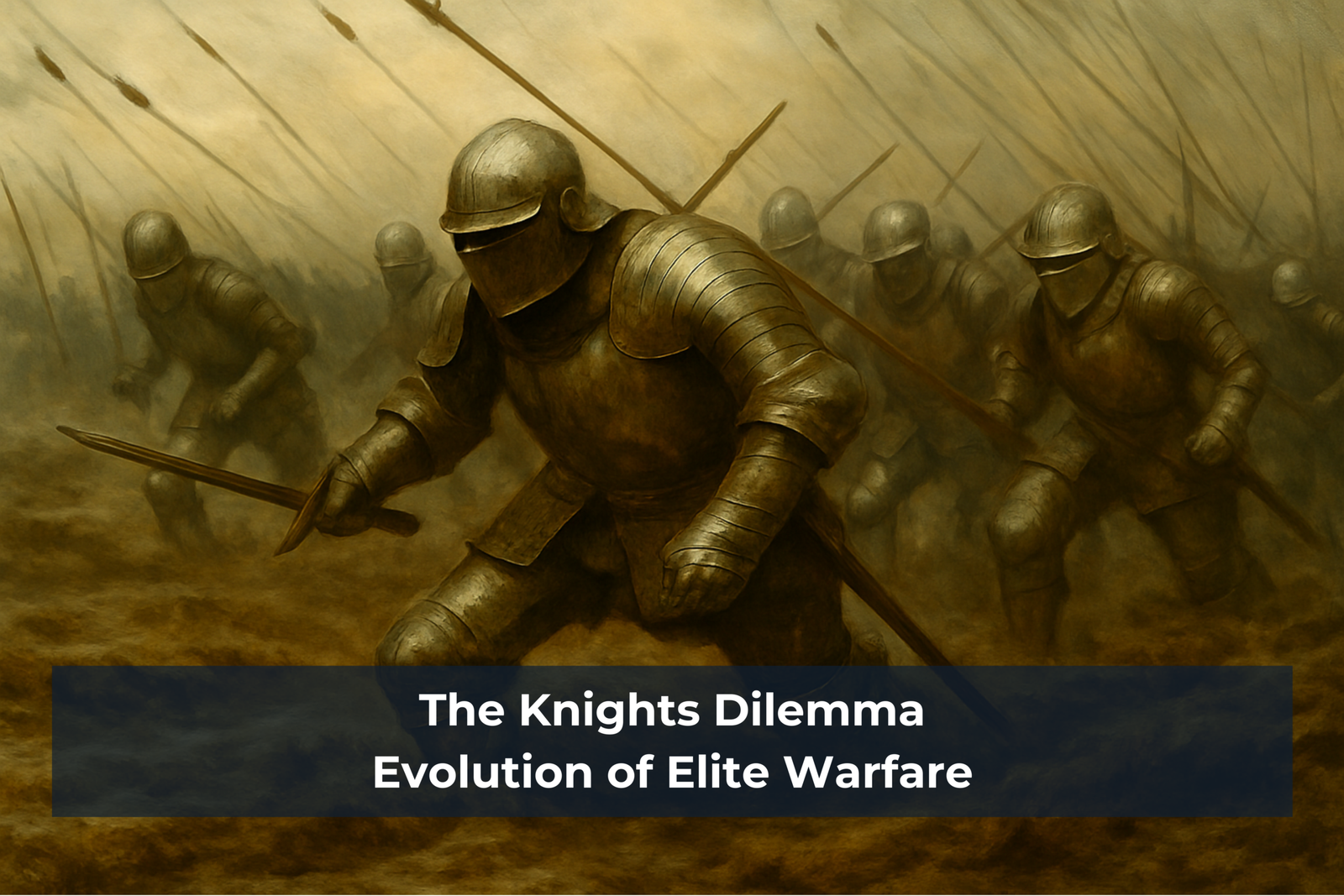

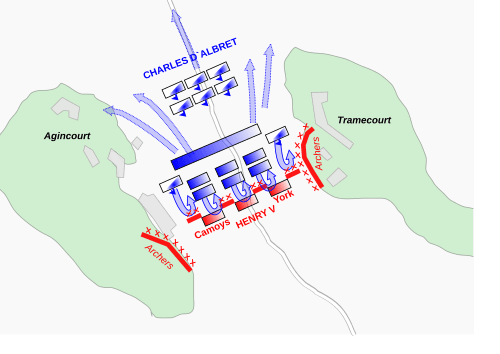

On October 25, 1415, in a muddy French field, the age of the knight began to die. The Battle of Agincourt was a collision of peak military capability, the feudal knight, and the battlefield introduction of cheap massed fires from the British longbow. Thousands of armored nobles, bound by centuries of skill, ritual, and pride, charged across rain-soaked terrain toward a line of English longbowmen. They did everything their code demanded, courage, discipline, frontal assault. The mud clung to their armor; and the arrows pierced more than their plate. Nearly a millennium of military supremacy dissolved in the mire in the face of a new battlefield technology. This article examines the tension between the evolution of elite warfare and the fundamental shifts in the context of war that undermine their relevance.

The Nature of War vs. The Context of War

The nature of war seldom changes, but its context is in a constant state of evolution. Agincourt endures because it captures a universal truth about elite military power: mastery does not guarantee relevance. The French knights were not tactically inept; the context of war changed. Perfection in an old paradigm did not create superiority in the new one.

Every generation of elite warriors face the same threshold moment. When the terrain, technology, or tempo of war shifts, the institution built on yesterday’s excellence must decide whether its culture will evolve or ossify. That decision rarely happens cleanly. It is constrained by myth, by the stories warriors tell about who they are, and what their sacrifices mean.

The modern special operator stands at an inflection point strikingly similar to Agincourt. They are exquisitely trained and equipped for close combat, yet cheap, massed precision fires make them largely ineffective. The equipment is different, but the pattern is the same: immense skill, narrow context, and cultural gravity pulling against change. The core attributes of peak warrior ethos remain, discipline, precision, restraint, fortitude, courage, intelligence, and an ethical code surrounding violence. Nothing about the individual in the arena needs to evolve in any meaningful way. However, the application of the warriors possessing these traits will face necessary tension as the manner of their employment evolves. The current environment rewards attributes the traditional elite warrior rarely prizes: dispersion, anonymity, and indirect methods.

The question, then, is not whether elite forces still matter, they do, but whether the mythos of what they were now impedes what they must become.

Inflection Points in the Decline of Mastery

History does not erase its elites overnight. It erodes them through moments of mismatch, when systems built for dominance encounter an environment that no longer values their strengths. Each inflection point reveals the same pattern: tactical brilliance persists, strategic logic fails, and culture becomes a cage.

Agincourt – The Democratization of Lethality

At Agincourt, the knight’s extinction began not with defeat, but with disbelief. The French refused to accept that mud and commoners could undo them. They fought as they always had, disciplined, courageous, but maladapted to an era where massed fire could outpace valor. The longbow did not merely pierce armor; it pierced the social order that armor represented. Training, lineage, and personal mastery were no longer enough. The longbow was a simple, low-cost weapon that an ordinary yeomen could master with modest training. It was an accessible weapon that could be mass produced and competence could scale evenly along side it. The ability to apply cheap, scalable massed ranged fires overturned centuries of aristocratic advantage.

The knights’ downfall arose from conviction, the unshakable belief that their mastery would always matter. They were so defined by what made them elite that they could not imagine a fight that did not need them. And in that blindness lies the first rule of decline: elites rarely die for lack of ability; they die defending the meaning of their ability.

Tokugawa Japan – The Weaponization of Peace

The samurai faced the same tension under different conditions. When the Tokugawa Shogunate unified Japan in 1603, it created 250 years of internal peace. The samurai’s battlefield function evaporated, but their identity endured. The sword became ceremonial, the warrior a bureaucrat, and Bushidō, once a living ethos, turned into doctrine.

Instead of evolving toward intellectual or technological mastery, the samurai codified nostalgia. The very code that had once guided resilience hardened into ideology. Two centuries later, that rigidity produced its own Agincourt: the Satsuma Rebellion, when thousands of armored swordsmen charged rifle lines in one final, beautiful, futile gesture. The lesson was not that courage had failed, but that courage, unaligned with reality, becomes tragedy.

The OSS and SOE – Battlefield Shaping & Preperation

The Second World War demanded new ways to project power into denied territory and prepare the ground for conventional campaigns. Across occupied Europe, Allied planners required intelligence, sabotage, and organized resistance to weaken the enemy’s depth before invasion. To meet this need, the British Special Operations Executive and the American Office of Strategic Services were created as instruments of preparation—tasked to penetrate deep behind enemy lines, disrupt critical infrastructure, and unify local forces under coherent direction.

Their work linked the clandestine with the conventional. Resistance movements gathered intelligence on enemy dispositions, executed sabotage to isolate battlefields, and guided airborne and amphibious assaults to key objectives. Through these efforts, the OSS and SOE extended maneuver into terrain not yet reached by armies, shaping conditions for success long before the first divisions landed.

When the war ended, the requirement for large-scale resistance faded, but the operational logic persisted. The intelligence and organizational elements matured into the Central Intelligence Agency, while the paramilitary and direct-action capabilities evolved into modern special operations forces. Both retained the same premise: that the decisive battle begins long before it is fought, and that shaping the battlefield is as vital as maneuvering upon it.

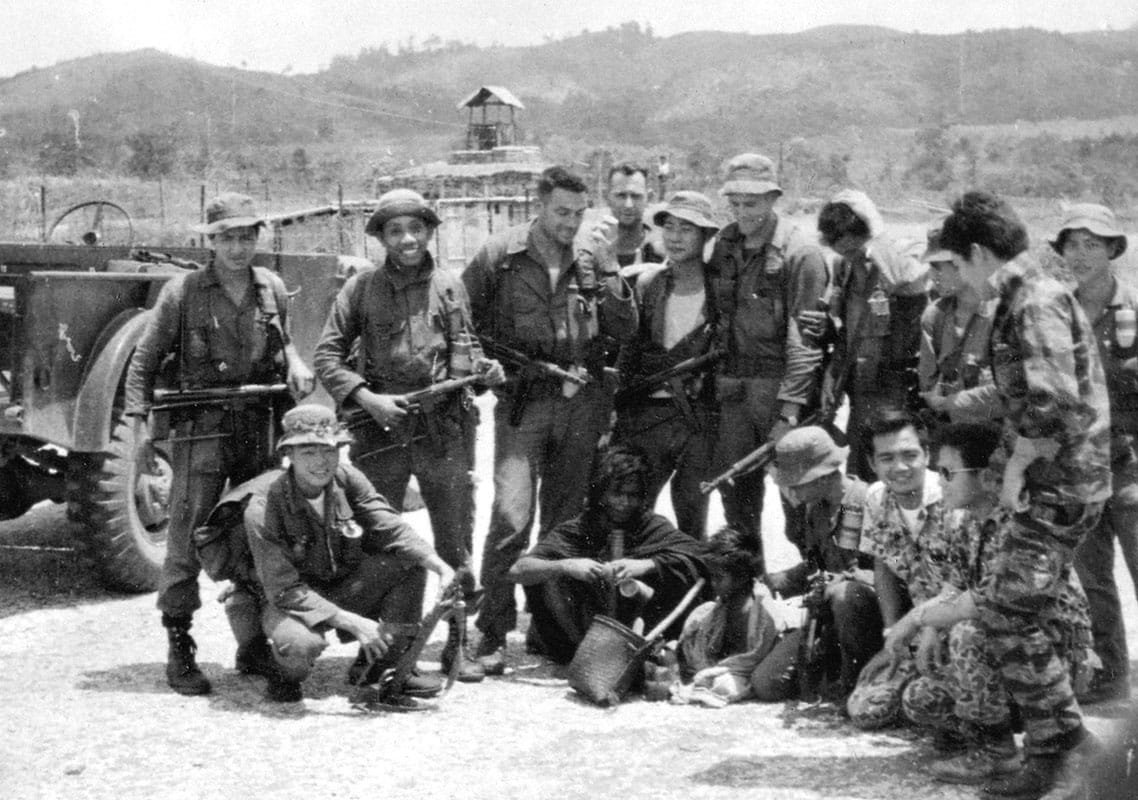

MACV-SOG

Two decades later, in the jungles of Southeast Asia, the cycle repeated. A new environment produced a new form. Covert reconnaissance and sabotage teams emerged to meet the war’s unique demands; dense terrain, denied borders, and a political need for plausible deniability. Deep behind enemy lines, in Laos and Cambodia, they used fieldcraft, deception, and local partnership to shape the fight from the margins, disrupting the logistic veins that sustained the enemy’s reach.

Operating largely unseen, these teams emerged from the battlefield’s shifting demands. Small, partnered, and deniable, they moved through terrain that defied conventional maneuver and relied on relationships as much as equipment. Their missions blended reconnaissance and sabotage into a single continuum of action. SOG embodied a form of warfare shaped by necessity—fluid, local, and adaptive to the environment rather than to doctrine.

When the war ended, so did the conditions that had called them into being. The labyrinth of jungle trails, the need for deniable presence, and the reliance on local networks all receded. SOG was dissolved, and its methods scattered into after-action reports. But the logic behind it endures, the alignment of force to environment, and of structure to need. Every battlefield change gives rise to such contextual adaptations, until the next transformation demands something new again.

The Mossad Pager Attack & Operation Spiderweb

There are lessons to be learned from the adaptations in current conflict zones, albeit not necessarily direct lessons. The underlying principles at play can be instructive as to how the context of the modern environment shapes engagement strategies.

For instance, a more recent inflection displayed the power of slow burn clandestine work rather than instantaneous spectacle. Over the course of roughly a decade, an Israeli intelligence campaign placed and maintained thousands of sabotaged communication devices across target networks. Thus creating a vast, low-visibility architecture for selective effects. The operation’s value was it’s sustained presence, and the ability to convert that preparation into action at a time of its choosing. It’s significance is not the method itself, but the lesson that patient preparation, remote and indirect approaches can achieve effects that may not be achievable at the same scale by other means.

Ukraine’s “Operation Spiderweb” illustrated a similar adaptation in distributed lethality. By embedding small autonomous drone systems in key areas across thousands of kilometers of adversary territory by unwitting participants, it demonstrated that the operation, not necessarily the technology can be the exquisite component. The spiderweb campaign struck at strategic bomber bases deep inside Russia without ever placing a human at risk inside the battlespace.

The operation was remarkable not only for its reach but for what it displaced. Heroism, once tied to proximity and exposure, was replaced by orchestration, networks, logistics, and timing. It showed that modern strength lies in the ability to produce simultaneous, deniable, precise disruption at scale. Both the pager attack and spiderweb demonstrated, via different modalities and against very different types of threats, that proximity and results are not necessarily linked.

The Pattern Repeats

A single thread runs across these moments: obsolescence begins when culture protects prestige faster than it adapts to pressure. And historical adaptations in force design and employment don’t tend to outlive their specific context.

- The Knight: highly trained, heavily armed; unmatched ability to close with and destroy like or weaker targets. Outmatched by cheap massed fires from peasants.

- The Samurai: discipline and honor personified. The perfect swordsman meets the basically trained rifleman.

- OSS/SOE: Borne of unique demand and bespoke purpose in total war. Disassembled and dispersed into intelligence, and the forerunners of special forces.

- SOG: Designed to solve problems of political sensitivity in third country sanctuary’s in order to keep a regional war inside the box, and out of the headlines.

Every time the context of war changed, the elite insisted it had not. Each believed its mastery was timeless. Each mistook institutional continuity for strategic necessity. Effective contextual units emerged with demand and in extremis, not before it anticipatorily. And they rarely survived as an organization past the context of their formation.

The the lesson of the knight and the samurai is not that elite units fail to evolve, but that they delay evolution until crisis forces it, and by then, the cost is higher, and the capability is hastily assembled. In economic terms, it is a sunk cost problem: the greater the investment in legacy systems and mythos, the harder it becomes to abandon them, regardless of diminishing return. If battlefield context can be determined earlier, the transitions can be smoothed, but probably not eliminated.

When OSS, or SOG was disassembled, the parts went back into a box, e.g. CIA and Special Forces. The raw material was preserved, to be reforged into the appropriate tools of the next battlefield context. The question remains, how do we know what to build and when to build it? How much and what type of raw material needs to be maintained to draw from?

Failure as The Impetus For Change

Many of the most consequential reforms in military history are borne of failure. Institutional learning is usually reactive: a costly failure exposes a mismatch, public scrutiny forces change, and policymakers convert lessons into new doctrines, training, or procurement. That cycle produces improvement, but it also imposes a high price in lives, credibility, and momentum.

Consider three paradigmatic examples. In the wake of a high-profile, failed hostage-rescue attempt at a remote desert staging area in 1980 (Operation EAGLE CLAW), national leaders confronted glaring gaps in interservice coordination and special operations command and control. The shock of failure precipitated a suite of policy reforms: changes to joint command relationships, new authorities for special operations, and reorganized procurement and training pipelines. The reorganization took years, but it produced institutional structures better suited to the complexity of modern joint operations.

A similar dynamic followed the urban firefight that exposed shortcomings in urban entry, aviation support, and casualty recovery in 1993. The operational trauma prompted new emphasis on realistic urban training, improved tactical aviation doctrine, and refined insertion/exfiltration planning; changes that, over time, influenced unit composition and pre-mission rehearsal standards. This specific event is likely the starting point for the current arc of the modern special operator. The urban hyper-tactical force build with the raid as is core purpose followed by two decades of growth, innovation, and success.

These cases share a truth: reform follows failure because failure makes problems visible, politically urgent, and impossible to ignore. That pattern can deliver real gains. But it is inefficient and avoidably costly when anticipation could have revealed vulnerabilities earlier. The strategic aim should be to invert the sequence, to normalize constructive failure in controlled settings using real future problems, so that the hard lessons occur in exercises and experiments rather than in the field. Special Operations need a cultural shift toward an acceptance of failure in training as a desirable outcome for anticipatory innovation, and precision evolution.

The Modern Parallel: Mythos and The Feedback Loop

For modern special operations institutions, the pattern is familiar even if the weapons are not. Their record over two decades of counterterrorism is extraordinary, precision raids, hostage rescues, and deniable operations executed at a tempo unmatched in military history. Yet success breeds sanctity. Every generation of elites eventually mistakes its mythology for its mission.

The Institutional Comfort of Mythos

Myth serves a necessary purpose in elite communities. Here, “myth” refers not to falsehood but to mythos, the collective narrative that encodes a community’s values and ideals. It is the story a society tells itself about what courage, honor, and mastery mean. It binds individuals through shared sacrifice and offers moral clarity for work that exists in legal and ethical gray zones. But myths also calcify. They reward repetition over re-examination. Within every elite force, culture becomes identity armor, protective, polished, and dangerously heavy.

Over time, language, imagery, and internal rituals harden into identity. Training pipelines become rites of passage rather than tools of adaptation. The iconography, night vision silhouettes, subdued patches, immaculate kit, and high-tech rifles, transform from identifiers into talismans. What began as outward indicators of tactical discipline and innovation become substitutes for evolution. This process is self-reinforcing. Popular culture amplifies the image; recruitment marketing leans on it; funding follows it. The myth feeds the institution, and the institution feeds the myth. It is a feedback loop that ensures prestige survives even when context shifts.

At peak mythos, the imagery escapes its origin. Law-enforcement units, private security, and skilled amateurs begin to mirror the look and language of the elite, turning useful operational aesthetics into a theatrical performance of mastery. Yet an adopted appearance rarely carries the discipline that designed it, the ten thousand hours of repetitions, the restraint, and the moral code, the sacrifice that gave the image its meaning.

A World That Rewards Anonymity

The environment that produced the modern elite special operator is vanishing. Decades of multi-domain dominance, persistent unilateral intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), total air superiority, extensive medical & logistics networks and robust command and control enabled the growth of the modern paradigm. When both sides are competing for that dominance, the precision SOF raid far less relevant. Any observable action inside the range of precision or massed fires, or under the view of adversary sensors, risks annihilation.

- Sensor saturation means that battlefield stealth is now fleeting.

- Precision and mass link detection to destruction.

- Containment and escalation favor deniability.

In this battlespace, visibility is vulnerability. The decisive actors are not those who can move fastest through a door, but those who can shape what that door leads to in the first place.

The Mossad pager operation and Ukraine’s spiderweb campaign demonstrate this inversion. Both were elite endeavors, painstaking, deniable, and devastating, but neither relied on physical presence. Their power lay in orchestration, systems thinking, and psychological leverage. They are case studies in what modern mastery looks like when stripped of mythic aesthetics.

This evolution does not diminish the human element; it reframes it. The new elite action is measured less by physical courage under fire but more by the foresight to avoid fire entirely while achieving the same ends.

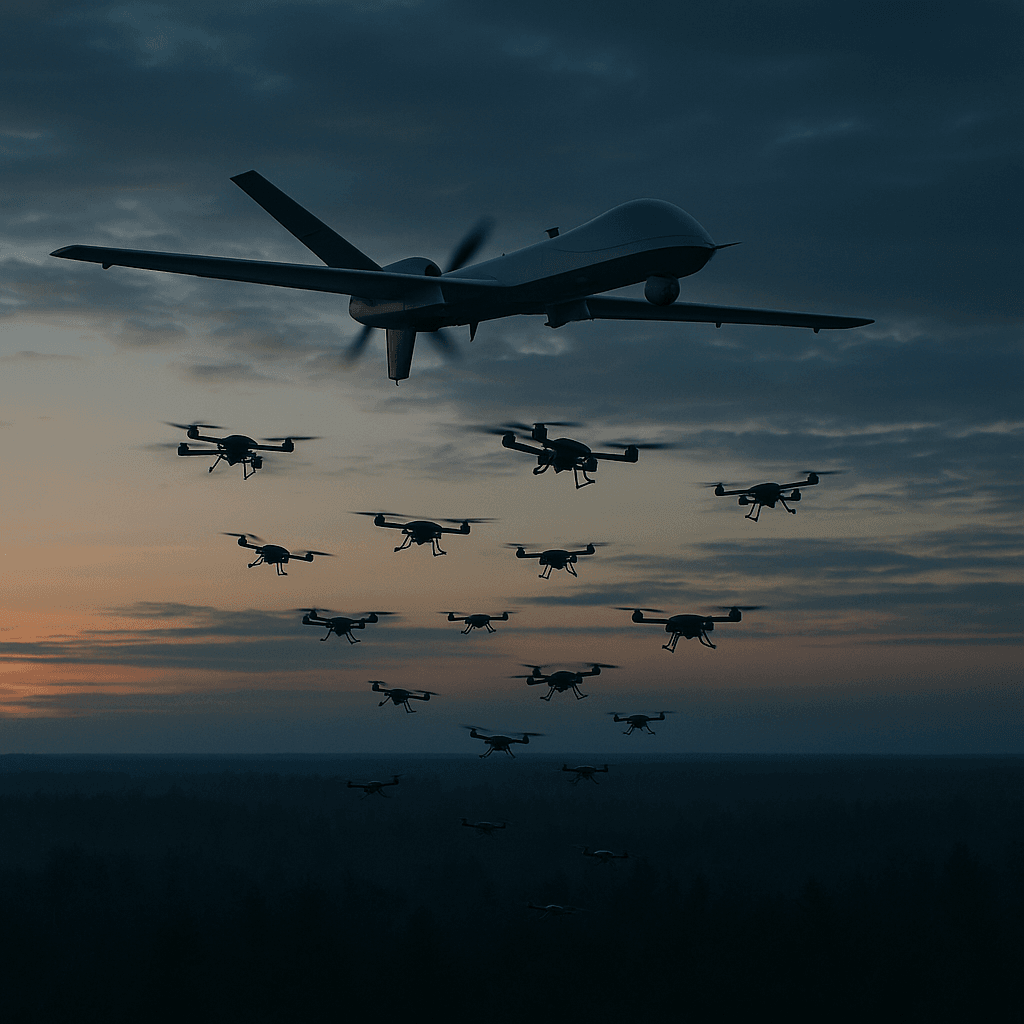

(AI-generated image)

Cultural Gravity and Bureaucratic Drift

The deeper problem is institutional. Elite systems develop bureaucratic immune systems that reject new DNA. They vet innovation for pedigree rather than performance, rewarding lineage over disruption. Myths of selection and sacrifice reinforce this bias: “not made here.”

This culture preserves excellence but punishes deviation. When success depends on anticipating unorthodox threats, cyber infiltration, information manipulation, deniable proxies, rigid hierarchy becomes a liability. The same discipline that ensures reliability can also ensure irrelevance.

Modern special operations organizations still possess extraordinary capability, but their ecosystems are optimized for kinetic certainty, not cognitive complexity. Their legends were built on direct action; their future will hinge on indirect effect.

If that transition feels uncomfortable, it should. The knight felt the same as he watched clouds of arrows fall.

When Mastery Becomes a Mirror

The paradox of mastery is that it encourages self-reference. Operators become experts in themselves, training to perfection within a model that no longer describes reality. Exercises simulate problems that technology and adversaries have already outgrown. Success inside the institution becomes increasingly disconnected from success in the field.

This internal coherence can feel like incremental progress, but it often signals closure. Institutions begin to measure themselves by their own myths rather than by the environment that myth was designed to navigate.

The cultural incentives reinforce the illusion:

- Commanders are not promoted for failing to achieve an objective with the force they were given. Therefore the test is drafted to be passed with the forces on hand.

- Friction is frowned upon. Innovation is only ‘ok’ within the scope described by the resource driving headquarters. Raid this building, but do it with drones. Not stopping to ask why are we rehearsing a raid in the first place.

- The audio doesn’t’ match the video. Loudly pronounce we need to change, while putting up fast rope posters in the recruiting stations.

How we measure ourselves is based of what we know of the past, not how we will be used in the future. The image we project mirrors the same iconography. Breaking from the process and imagery of the mythos is akin to career suicide.

The Modern Knight’s Dilemma

Today’s elite warrior faces the same decision that confronted the French Knights at Agincourt and the samurai of Satsuma: remain faithful to a perfected form, or risk imperfection to survive. The temptation to preserve identity is powerful, and the cost of delay is existential.

Adaptation does not mean discarding virtue. Discipline, courage, and restraint remain the foundation of legitimacy. But they must now coexist with intellectual flexibility and technical humility, qualities that rarely fit the myth of the stoic, silent professional.

The world is converging toward systems integration, remote orchestration, and persistent competition short of war. The next decisive acts will occur in servers, supply chains, and sensor networks, not in compounds under moonlight. To remain relevant, elites must treat myth as inspiration, not instruction.

Breaking the Pattern

The end of an era rarely announces itself. It arrives quietly, through subtle shifts in what no longer works, and louder insistence from those who refuse to notice. The knight’s final error was loyalty to a form that was no longer relevant. Every modern elite force faces that same test: how to preserve meaning without preserving method.

Preserving What Endures in The Evolution of Elite Warfare

Not everything should change. Certain traits are elemental to any professional warrior class; discipline, courage, resilience, composure, moral restraint, and the willingness to bear risk on behalf of others. These are the connective tissues that link centuries of soldiers, spies, and saboteurs.

The danger lies in mistaking these virtues for the forms that once carried them. The code of chivalry, Bushidō, or modern notions of quiet professionalism are valuable only when they produce adaptability, not nostalgia. Honor should describe conduct, not costume. If the emblem or motto requires defending more than the mission, the institution has inverted its purpose.

Hostage rescue, precision counter-violent-extremist operations, and direct action against non-state actors remain core domains where legacy expertise still matters. These tasks require the combination of surgical timing, discretionary judgment, and moral discipline that only sustained, high-fidelity training produces; there are few credible substitutes when lives are on the line or when political deniability constrains broader options. But they also demand an operating environment that requires multi-domain dominance, or the ability to achieve it, to succeed at scale.

These missions now represent a specialized slice of the modern force, not its center of gravity. Their focus must endure, but in proportion to their true operational demand, ensuring that the broader enterprise evolves toward distributed, systems-level competition without losing the sharp edge required for those narrow, high-risk actions.

Reframing the Ethos

The current manifestation of this cognitive dissonance appears in the language of reform itself. “Lethality” has become the rallying word, an assertion of relevance through volume of fire rather than precision of effect, and drones serve as the favored instrument of innovation. The fixation on the language of direct action and high tech tools, reflects a deeper anxiety: when identity is threatened, institutions double down on the tools that once signified dominance, even as the environment rewards distance and indirect approaches.

A metaphor for how organizational change is playing out can be summed up as, “just give the knights their own longbows”. The historical inflection points show that elites fail not because they lack bravery, but because they lack permission to reimagine who they are, and where they are necessary.

The Choice of Armor

Every institution must decide whether its building a culture of protection or confinement. Armor once symbolized strength because it allowed warriors to close distance. In today’s operational and informational battlespaces, the ability to close distance is no longer a virtue, it is often a liability.

Precision, proportionality, and restraint remain the moral high ground. Everything else, the posture, the myth, the form, must remain fluid.

At Agincourt, the French knights believed the mud was their enemy. In truth, it was their teacher. The context of war had changed; they had not. Modern elites stand in similar terrain, heavy with honor, certain of their excellence, yet surrounded by signs that the world no longer fears what they once mastered.

The task now is not to mourn the knight, but to reimagine his form for a battlespace where silence, subtlety, and systems thinking define strength. Armor still matters, but only in the narrow context where its dominance still applies.