Update (January 2026): In a major escalation of U.S.–Venezuelan tensions, U.S. special operations forces conducted a surprise military operation in early January 2026 that resulted in the capture and removal of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and his wife from Caracas; both were transported to New York to face federal narco-terrorism charges. Maduro’s departure has created a contentious power vacuum with Vice President Delcy Rodríguez installed as interim president amid ongoing political division and military uncertainty. The decapitation raid marks a shift in the conflict’s trajectory and alters resistance dynamics across Venezuelan society.

Tension between Venezuela and the United States has intensified, reflected in the massing of military forces, attacks on small watercraft, and a sharper political confrontation. These developments warrant a clear assessment of how Venezuelan society might react if foreign ground forces appeared on its territory.

How would social structures, armed groups, and political factions respond under the shock of invasion? Venezuela is marked by economic hardship, contested authority, difficult terrain, pervasive lawlessness, and deep grievance. These conditions shape the country’s potential for resistance to foreign intervention and insurgent mobilization. Examining them in advance helps clarify how irregular warfare risks should inform decisions about employing U.S. ground forces.

Why Regime Change and Stability Operations Require Insurgency Analysis

Historical case studies demonstrate that forcible entry by foreign forces is often the simplest phase of armed conflict. Complexities emerge when populations attempt to adapt to new political realities. Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam, and Libya illustrate how local networks reorganize once central authority shifts, and these reorganized networks often become the foundations of resistance movements.

Populations tend to absorb political disruption and then gravitate toward actors who provide identity or protection. Resistance is often the activation of existing social networks rather than a phenomenon created from external pressure alone. When authority shifts, individuals recalibrate expectations and group loyalties. These changes influence whether resistance forms, how it forms, where, and how it sustains itself.

Analytical Purpose

The purpose of this article is to examine the structural and behavioral conditions that could influence resistance or insurgent potential in Venezuela during a hypothetical U.S. ground intervention. This article does not argue for or against such an intervention. It does not evaluate policy choices. It identifies irregular warfare variables that research suggests would shape population behavior under conditions of political disruption. This assessment is grounded in established irregular warfare frameworks and can serve as a tool to assess strategic risk in military ground interventions in Venezuela.

The aim is to provide an empirically anchored foundation for understanding how populations adapt when authority becomes contested during the presence of foreign military forces. This article will map demographic factors, legitimacy perceptions, preexisting armed structures, geographic constraints, foreign sponsorship patterns, and emerging technologies that influence irregular conflict. It will outline pathways that research suggests could shape participation, auxiliary activity, or insurgent emergence. It will remain grounded in open source information and established scholarship.

Why Venezuela Requires Structured Analysis

Venezuela contains a caustic mixture of armed civilian groups, criminal networks, economic strain, and fragmented political opposition. These elements interact with each other in ways that inform any post regime change realities. The Assessing Revolutionary and Insurgent Strategies (ARIS corpus) notes that resistance movements frequently grow from preexisting networks inside a society. This potential landscape in Venezuela includes colectivos, informal governance groups, and armed syndicates with established recruitment channels, territorial influence, and cross border clandestine illicit networks.

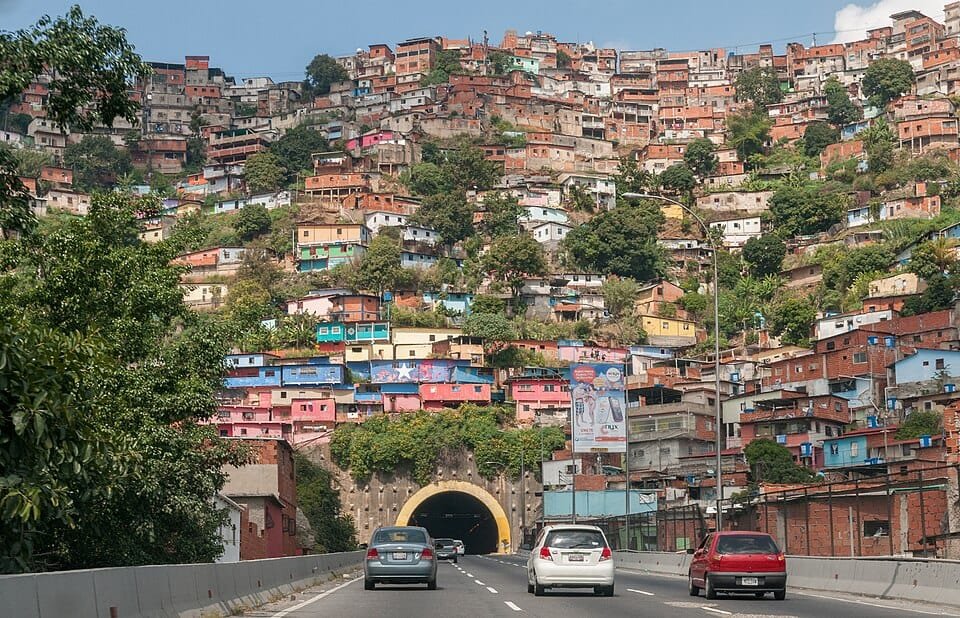

The capitol of Caracas presents an additional layer of complexity due to its size, density, and social compartmentalization. Megacity environments shape population behavior as well as creating the physical conditions that influence how auxiliary and underground structures form. Notably, undergrounds and auxiliaries thrive where anonymity, density, and fragmented authority provide opportunities for concealment and adaptation. This article unpacks the empirical, and theoretical potential of a mobilized irregular warfare apparatus in Venezuela.

Legal Narratives, Legitimacy, and the Political Psychology of Resistance

In any foreign intervention, local interpretation of legality becomes a primary driver of early population behavior. This is not solely a matter of international law. It is a matter of narrative construction inside the affected society. Legitimacy is the first filter through which a population interprets external actors. Individuals evaluate whether the presence of foreign forces aligns with their sense of justice, sovereignty, and collective identity.

Jus ad bellum concepts influence these interpretations. Populations do not separately evaluate legality, morality, and identity. They blend them into a single judgment about whether an external force is acting as a stabilizing presence or an intruder. If a foreign intervention is framed by the host society as unauthorized, coercive, or improperly motivated, resistance potential increases. This judgment does not require deep legal knowledge. It flows from intuitive assessments grounded in national history and political identity.

Venezuela’s political environment heightens this sensitivity. The state has cultivated narratives of sovereignty, anti-imperialism, and resistance to external pressure for decades. These narratives create fertile conditions for rapid mobilization once foreign forces appear, since the mental framework for interpreting foreign involvement already exists. Populations use preexisting narratives to make sense of sudden political shocks and Venezuela has several such narratives within the collective psyche that are readily available for activation.

The Legitimacy Paradox and the Role of National Identity

A foreign intervention can produce a legitimacy paradox. Even populations that oppose their government can interpret external military involvement as an attack on national autonomy. The events in Ukraine during 2022 show a similar dynamic. External aggression effectively consolidated political unity, strengthened national resolve, and increased approval for leadership that had previously faced criticism. This does not imply identical outcomes in Venezuela, rather it demonstrates how external pressure often creates inward cohesion.

If Nicolás Maduro remains in place during a foreign intervention, he gains the opportunity to claim the role of national defender and this role does not require widespread genuine approval. It requires a narrative that the state can project and enforce. Leadership signals cand serve as influence tipping points which causes populations to shift from passive observation to active participation. A government portrayed as defending the nation can raise these thresholds and reduce the willingness of undecided civilians to cooperate with foreign forces. History is replete with governments in domestic peril engaging in diversionary conflict to rally the population against an “other”.

Should Maduro flee, the legitimacy landscape changes. Power vacuums weaken central narratives and open space for competition among political factions, armed groups, and local actors. Ted Robert Gurr’s framework suggests that political fragmentation increases perceived deprivation among groups that fear exclusion from post-conflict authority. This environment increases recruitment opportunities for resistance networks because individuals tend to seek security and identity during periods of instability. Whether Maduro stays or departs influences the shape and timing of mobilization, not the underlying drivers.

Regime Messaging and the Construction of Resistance Narratives

The Venezuelan state possesses mature propaganda and mobilization structures. These structures have been tested during economic collapse, sanctions pressure, and internal unrest. Messaging organs can rapidly frame a foreign intervention as a colonial intrusion, a threat to national dignity, or an attempt to seize resources. Such framing increases the likelihood that colectivos, militias, or local power brokers will adopt resistance roles.

ARIS Conceptual Typologies of Resistance outlines how states create hybrid environments where loyalist paramilitaries serve political functions that can transition into military ones. Venezuela has used colectivos to enforce political authority, distribute patronage, and intimidate opponents. In a foreign intervention, these organizations would likely attempt to position themselves as defenders of sovereignty. Their messaging would interact with state propaganda to form a layered resistance narrative across formal and informal channels.

These narratives influence auxiliary participation and resistance movements often rely on civilians who do not join armed groups but provide intelligence, supplies, and safe movement. Messaging that frames foreign forces as illegitimate increases auxiliary willingness. The population does not need homogenous support for armed resistance. It only needs enough decentralized willingness to complicate stabilization efforts.

Civilian Harm, Jus in Bello, and Mobilization Effects

How foreign forces conduct themselves also influences ones decision to join a resistance movement. Jus in bello considerations shape public perception. Civilian harm, infrastructure disruption, and perceived disrespect toward communities can accelerate grievance formation. Gurr’s model places grievance at the center of mobilization. ARIS research also notes that populations react not only to objective harm, but to the perceived fairness of force application.

Even disciplined military behavior can produce unwanted effects in megacity environments where density increases the likelihood of accidental harm. Each incident becomes a narrative tool for resistance organizations. Colectivos and political actors can use these events to frame the foreign force as indifferent or hostile. This framing influences undecided civilians who are seeking cues about whether cooperation is safe and legitimate. The repression of an insurgency is a mobilization factor unto itself and is referred to as ‘the repression-mobilization cycle’.

Legal framing is not a technical issue inside Venezuela. It is a political and psychological catalyst that influences how individuals judge authority and risk. These judgments determine whether resistance remains latent or becomes active. The combination of sovereignty narratives, regime propaganda capability, historical suspicion of foreign involvement, and the potential for leadership consolidation creates conditions where legitimacy becomes a decisive variable in the early phases of any foreign presence.

Demography, Social Behavior, and Mobilization Potential

Scale of the Military Age Population and Participation Thresholds

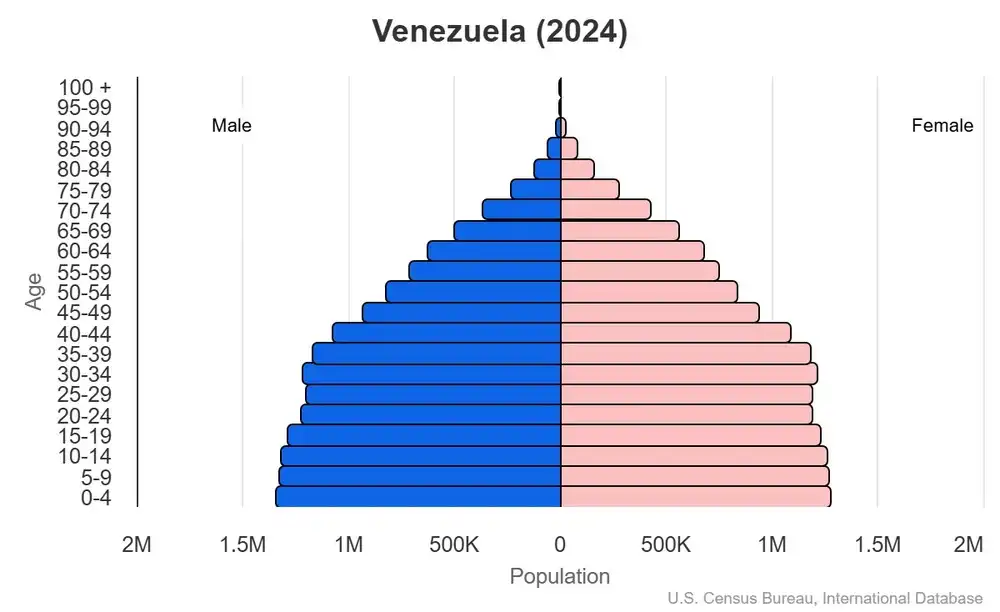

Venezuela possesses a large pool of military age individuals relative to its overall population. Demographers estimate that several million men fall within the age ranges most commonly associated with participation in armed resistance. This does not suggest that large numbers would mobilize. It establishes the size of the available pool. Research studies shows that ultimately participation thresholds depend on legitimacy, opportunity, economic conditions, and perceived grievance rather than raw population numbers.

Research by Erica Chenoweth identified that movements capable of mobilizing a small critical mass frequently unlock wider participation once individuals see that resistance is viable. While Chenoweth focused on nonviolent action, the idea that collective behavior spreads when observers perceive low risk applies across many forms of mobilization. Still, only a fraction of the population will ever join armed resistance while a larger segment may provide support when they believe it serves family, community, or political identity. In a setting where millions fall into the age range commonly involved in violent activity, even modest participation rates could create problems at scale.

Women, Violence Exposure, and Participation Roles

Gender norms do not always predict participation patterns in resistance movements. There are extensive cases where women serve in auxiliary or clandestine roles even when cultural norms discourage direct combat. Venezuela’s political history includes repeated episodes where women organized protests, maintained communication networks, and provided logistical support to opposition groups. This background suggests that participation would likely extend beyond military age males.

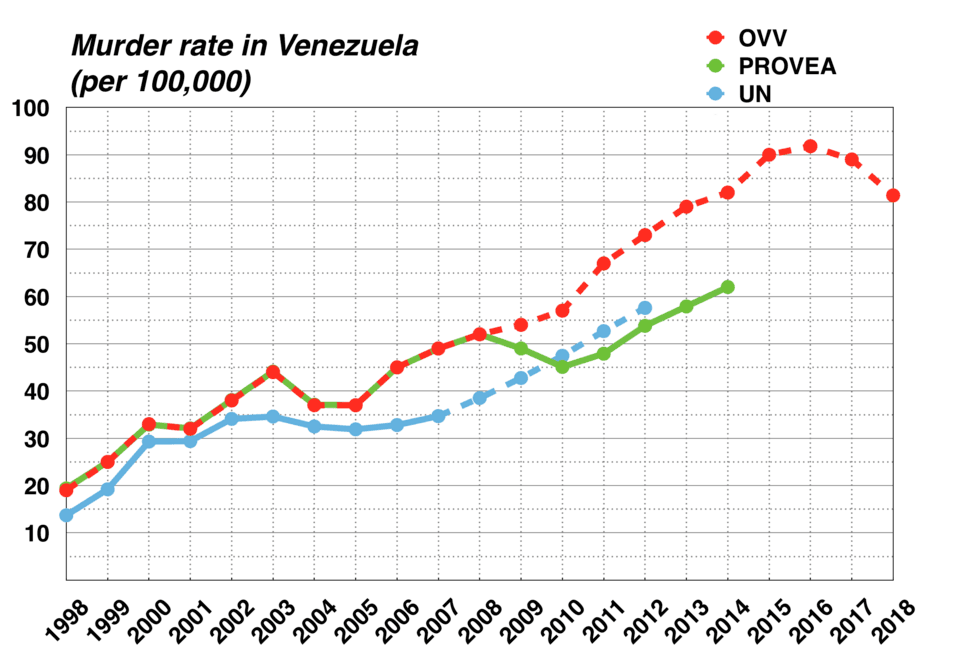

Venezuela’s high levels of interpersonal violence introduce another variable. Exposure to violence often shapes community tolerance for coercion, intimidation, and armed presence. Populations accustomed to high everyday risk may evaluate participation decisions differently than populations with low exposure to violence. They may also possess social networks that adapt quickly when political authority becomes contested.

Women often anchor these networks because they manage household logistics, maintain community ties, and interact with local institutions in ways that men do not. Their involvement rarely appears in early intelligence assessments, yet they frequently determine whether clandestine groups survive.

Violence Propensity as an Indicator of Resistance Potential

Venezuela has recorded very high homicide rates for many years. Analysts often use this metric to approximate the level of social stress, and the degree to which individuals interact with coercive environments. Furthermore, environments containing persistent insecurity and economic decline produce individuals who experience higher levels of relative deprivation. This perception shapes how quickly grievance transforms into mobilization.

Source: ZiaLater, 2014- CC-BY-SA 3.0.

A high baseline of violence does not automatically indicate future insurgent activity but it may indicate a baseline level for familiarity with or access to weapons. Underground structures flourish when communities already interact with actors who operate outside formal legal systems and Venezuela’s criminal groups and armed colectivos have established territorial control in several areas. These groups have created parallel structures that function independently of state institutions often referred to as shadow governance. Their presence lowers the psychological barrier for individuals to engage with alternative authority figures once central authority becomes disrupted.

Economic Stress and the Removal of Participation Barriers

Barriers to participation in resistance activities are any obligation or perceived consequence that tip the scales in favor of inaction. They include employment, education, family, caregiving responsibilities, and daily stability. These barriers directly influence the decision to join or support resistance activity and Venezuela’s economic collapse affects this calculus. High unemployment and underemployment reduce the opportunity cost of participation. Individuals who lack income or stability may view mobilization as a source of identity or security.

Economic hardship also reshapes daily routines. When individuals no longer travel to work or school, they spend more time inside communities where local networks exert greater influence. Community influence increases when formal institutions weaken and these conditions often create openings for armed groups or political actors seeking to expand local support or auxiliary capacity.

Criminal Gangs, Colectivos, and the Pivot Toward Resistance Roles

Criminal organizations inside Venezuela have developed hierarchical structures, logistics networks, and local governance roles. These structures position them to transition from criminal activity to resistance activity under certain political conditions. Insurgent movements often emerge from networks that already possess clandestine capability. Venezuela’s colectivos and mega bandas operate with discipline, familiarity with coercion, and local legitimacy within their territories.

Once foreign forces arrive, these groups may pivot into resistance roles and could frame themselves as defenders of national dignity or community stability. Groups that begin as political auxiliaries can transform into armed actors as conditions shift. In Venezuela, this transformation requires little structural change because many groups already possess weapons, leadership, and social cohesion.

Their presence increases the scale and speed at which resistance could emerge. While criminal and political armed groups rarely merge into unified movements, their simultaneous activity generates widespread security complications that shape early perceptions of stability.

Summary of Demographic and Social Mobilization Factors

Venezuela contains demographic and social elements that influence mobilization patterns during political disruption. A large population of military age men, the potential participation of women in auxiliary roles, high exposure to violence, economic instability, and the presence of armed networks create conditions where mobilization can occur rapidly. Irregular warfare scholarship shows that these conditions do not guarantee resistance activity, but they establish the structural environment in which individuals evaluate legitimacy, risk, and identity.

Political Structures, Social Fragmentation, and the Organizations That Shape Resistance

Regime Cohesion and the Architecture of Internal Control

Cuban intelligence advisors support functions inside the Venezuelan state strengthening the regimes ability to wield irregular networks. Elements of the security apparatus maintain loyalty through patronage networks, access to resources, and shared survival incentives. Regimes with strong internal surveillance and embedded foreign advisory support are able to activate early-stage mobilization.

Cohesion inside the security services shapes early resistance dynamics. Units with strong patronage ties may remain loyal, while others could fragment if they perceive regime collapse. Fragmentation opens pathways for irregular groups to gain equipment, recruits, and local legitimacy and perceived exclusion from power structures drives mobilization among groups that believe their survival depends on securing a new place within a shifting political landscape.

A Fragmented Opposition and Limited Mechanisms for Unified Mobilization

Venezuela’s opposition landscape contains many factions that vary in ideology, leadership structure, and strategy. This fragmentation limits the likelihood of a unified resistance movement forming in response to foreign intervention. Resistance movements typically require organizational coherence to generate coordinated action. When political factions lack shared vision, they often produce parallel but uncoordinated networks instead of a single organized front.

Fragmentation does not prevent resistance and foreign forces could encounter multiple localized resistance networks that respond to different leaders and motives. These networks may not collaborate, yet their simultaneous activity increases the overall complexity of the environment. Dispersed guerrilla efforts may still create cumulative pressure that exceeds their individual strength.

Civil Society Weakness and the Latent Capacity for Mobilization

Venezuelan civil society has been pressured for years by economic decline, political manipulation, and institutional degradation. Formal organizations have lost capacity, and independent institutions often operate with limited resources. Resistance movements do not always grow from strong civil institutions. They often emerge from informal networks that fill gaps left by weakened structures.

Widespread civic protests in past years demonstrated that Venezuelan society retains latent capacity for mobilization even without strong organizational leadership. These protests displayed high participation, rapid diffusion through social networks, and adaptability to state responses. Such characteristics align with Chenoweth’s findings that broad civilian mobilization relies more on social contagion and shared grievance than on formal structures. In a scenario where foreign forces appear, this latent capacity could be activated by local leaders, armed groups, or opportunistic actors seeking influence.

Narrative Competition and the Struggle to Define Legitimacy

Political narratives shape the interpretation of events during crisis. The Venezuelan state maintains control over key media channels and has experience framing opposition movements, economic pressures, and foreign criticism as coordinated threats. These narratives could be redirected to portray foreign forces as aggressors or destabilizers. Narratives influence whether populations interpret events as legitimate and whether they shift from passive observation to active participation.

Opposition groups would likely attempt to frame foreign forces in different ways. Some may welcome external assistance, while others may fear loss of agency or political displacement. Criminal organizations may frame themselves as protectors of their communities. This fragmented narrative landscape can pull the population in multiple directions, which complicates assessments of early resistance behavior. Individuals often rely on community leaders, local power brokers, and personal experience rather than national messaging to determine their stance.

Local Power Brokers and Informal Governance

Large segments of Venezuela rely on informal authority figures for daily security and access to services. Colectivos, syndicates, and territorial gangs fill governance gaps in many areas and these structures function as parallel governance system that can transition into auxiliary or resistance role once political authority becomes contested. Their influence will shape how civilians respond to occupatoin forces.

These groups can mobilize support or opposition by controlling information, coercing cooperation, or distributing resources. Their presence raises the complexity of early stabilization efforts because they may shift among criminal, political, and resistance roles depending on which identity serves their interests at a given moment. Their adaptability increases the difficulty of predicting population behavior across different regions.

Venezuela’s political landscape contains multiple pathways for resistance behavior. Regime cohesion, opposition fragmentation, weakened civil institutions, competitive narratives, and strong informal governance structures influence how individuals and groups respond to foreign forces. ARIS research shows that resistance emerges from social networks already in place, and Venezuela contains numerous networks capable of mobilizing quickly.

Geography, Terrain, Climate, and the Physical Constraints That Shape Resistance

Venezuela’s Geographic Challenge

Stratfor — YouTube · Published Nov 12 2012

Stratfor discusses the importance of Venezuela’s oil reserves and its relations with the United States.

The Geographic Structure of Venezuela and Its Influence on Conflict

Venezuela contains a diverse set of physical environments that shape how populations move, communicate, and organize during political disruption. Physical space is a key variable in how undergrounds and auxiliaries form. Each region of Venezuela creates different opportunities for concealment, mobility, and survival.

The Andes in the west contain elevated terrain, narrow movement corridors, and dispersed rural communities. These characteristics create natural compartmentalization, which influences how resistance groups communicate and sustain operations. The Orinoco Basin extends across the central and southern regions and includes river networks that facilitate both commerce and illicit activity. Communities along these rivers often maintain long-standing informal exchange routes that can adapt quickly when formal institutions weaken. The southeast includes jungle regions with sparse population density and minimal state presence, which creates sanctuary opportunities for armed groups seeking to evade detection.

These geographic features provide the physical scaffolding on which networks operate and geographic conditions influence participant behavior by shaping expectations about safety, mobility, and access to external support.

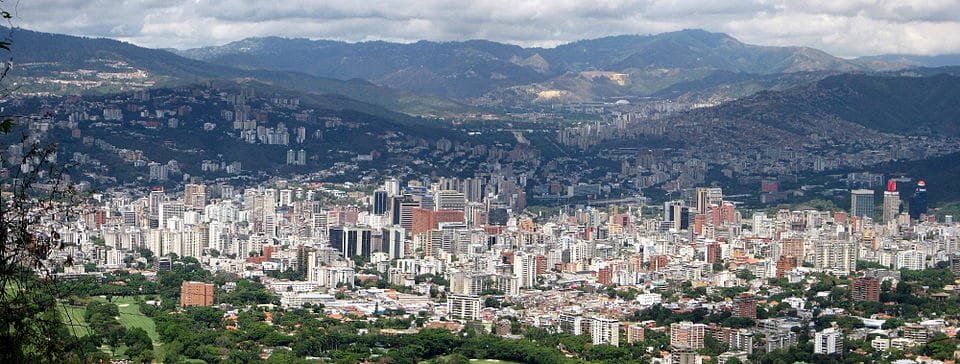

The Coastal Urban Belt and the Centrality of Caracas

The majority of the Venezuelan population lives along the northern coastal belt where major cities create dense human terrain. Caracas holds particular importance due to its size, geography, and social fragmentation. With an estimated population of around five million in the metropolitan area, Caracas functions as a megacity where topography and human behavior interact in ways that complicate stability operations.

The city is surrounded by mountains, which limit ingress routes and create natural choke points. Inside the city, neighborhoods are separated by steep gradients, irregular street patterns, and dense construction. These features create multiple micro-terrain environments within a single urban space. Density, anonymity, and physical complexity support clandestine activity by providing concealment and multiple pathways for movement.

Caracas contains large urban barrios where informal governance structures and armed groups already exert influence. These areas form environments where resistance organizations can blend into civilian populations, maintain supply networks, and conduct activity with limited visibility. Stabilization efforts in megacities often require large force footprints and sustained engagement because armed groups exploit complexity to preserve freedom of movement. The size of Caracas alone becomes a significant variable in any intervention scenario.

Rural and Frontier Zones and Their Role in Resistance Activity

Rural regions along the borders with Colombia and Brazil contain forests, rivers, and limited infrastructure. These areas provide natural sanctuary conditions that armed actors can use for rest, training, or evasion. Sanctuary influences the decision to escalate activity because safe retreat options reduce perceived risk.

The frontier with Colombia has a long history of illicit movement involving smuggling networks, FARC dissidents, and local armed groups. These networks maintain familiarity with cross-border travel, supply chains, and communications. If central authority becomes contested, these routes could support movement of personnel or resources for resistance activity. The border with Brazil contains remote jungle terrain that increases the difficulty of surveillance and enforcement. These spaces do not ensure durable resistance but create the physical environment that allows groups to reconstitute.

Climate, Health, and the Operational Environment

Venezuela’s climate includes high humidity, significant rainfall, and heat that affects both civilian activity and military operations. In hot and humid zones, mobility slows and individuals rely more on local networks for assistance. This pattern benefits groups that already possess strong territorial presence, such as colectivos or syndicates.

Disease also plays a role. Malaria remains present in southern regions and dengue appears in urban and peri-urban areas. Public health capacity has declined due to economic pressures. In environments with weakened medical systems, populations often depend on informal networks for care. These networks can overlap with auxiliary structures that support resistance activity. Disease and climate do not cause mobilization, but influence how individuals weigh participation decisions and how groups sustain themselves.

Terrain as a Determinant of Stabilization Complexity

Terrain influences the size of the force required to maintain order and the ease with which resistance groups can operate. In megacities, narrow streets, vertical structures, and dense populations increase the likelihood of concealment and complicate early identification of armed actors. Urban density increases the survival rate of clandestine groups because they can disperse rapidly and blend into civilian patterns.

Rural sanctuary zones require different stabilization strategies that rely on sustained presence, mobility support, and coordination with border authorities. The combination of megacity terrain, rural sanctuary, and complex riverine environments increases the number of distinct operational challenges foreign forces must navigate. Each terrain type shapes resistance behavior in different ways and requires tailored approaches to mitigate the emergence or persistence of armed activity.

Venezuela possesses geographic conditions that influence how resistance forms, sustains itself, and expands. Mountain regions, jungle areas, river basins, rural frontier zones, and a dense megacity create multiple environments where armed groups and auxiliary actors can operate, potentially with impunity. Resistance movements exploit environments that provide mobility, concealment, and sanctuary and Venezuela has all three of these features within a relatively small geographic space.

Foreign Sponsors and External Actors That Shape Resistance Potential

The Role of Cuba, Russia, and Iran in Strengthening State Security Networks

Venezuela maintains long-standing relationships with nations hostile to the United States that provide political support, intelligence cooperation, and limited military assistance. These relationships influence resistance dynamics because they shape how quickly the government can adapt. Cuban intelligence personnel have supported Venezuelan security institutions for years. Their presence strengthens the regime’s internal surveillance, counterintelligence practices, and control over key leadership nodes.

Russia has supplied training, equipment, and advisory support to Venezuelan security forces. Russia’s involvement increases the state’s ability to manage information, conduct electronic surveillance, and sustain internal cohesion during political shocks. Iran has provided expertise in UAV development, security cooperation, and ideological engagement with elements aligned to the Venezuelan government. These relationships shape the environment foreign forces would enter by increasing the capability of the state and its capacity to foment resistance to invasion disrupt occupation or stabilization operations.

China’s Strategic Incentives in a Venezuela Crisis

China maintains economic investments in Venezuela and shows interest in scenarios that require the United States to commit large military or political resources away from other regions. Large-scale U.S. ground operations in South America would divert attention and assets that support strategic efforts in the Indo-Pacific. External actors often seek to exploit conflicts that strain the resources of major powers. China benefits when the United States disperses attention, and a prolonged irregular conflict in Venezuela would create such conditions.

Additionally, China is able to provide technologies that influence how foreign forces are perceived and how quickly resistance narratives spread. While China does not need to provide direct military assistance its economic and technological role can alter the balance between state resilience and opposition mobilization.

External Actors as Force Multipliers for Resistance Movements

Foreign actors can influence resistance behavior even when they do not directly support insurgents. Populations evaluate foreign involvement when assessing risk and opportunity. If civilians believe that powerful states support the government, they may perceive resistance as more viable. If civilians believe that external actors will sustain the conflict or weaken foreign intervention forces, resistance becomes more attractive.

In Venezuela, the presence of Cuban, Russian, Iranian, or Chinese advisors would likely reinforce the perception that the government possesses external backing. This perception can increase resistance activity directed at foreign forces because individuals may believe that external support enables the government to wage a longer or more intense struggle. The perception of a long conflict can create psychological space for armed or auxiliary groups to expand.

Source: Kremlin.ru, 25 Sept 2019 (CC BY 4.0)

Foreign Support to Armed Networks and Illicit Structures

Venezuela hosts armed networks that maintain cross-border links with actors across the region. FARC dissidents have used parts of southern and western Venezuela for safe passage, training, and logistics. These networks connect to criminal organizations involved in smuggling, drug production, and weapons trafficking. Movements with access to illicit funding and cross-border sanctuary often generate longevity and adaptability.

These networks do not require foreign states to function. Their existence, however, interacts with external political support and creates layered complexity. Armed groups may secure supplies, move personnel, and access communication channels outside the reach of central authority. These conditions reduce the ability of foreign forces to control escalation and increase the likelihood that resistance persists even if the Venezuelan government weakens.

The External Information Environment and Narratives of Resistance

External actors influence narrative formation through media, diplomatic engagement, and information campaigns. State-aligned outlets in Russia, Iran, and China frequently frame U.S. actions abroad as destabilizing or coercive. These narratives can be amplified inside Venezuela, where they intersect with existing sovereignty themes and anti-intervention rhetoric. Narratives influence individual decisions to join or support resistance by shaping the perceived legitimacy of action.

If foreign information channels portray resistance as a patriotic duty, they influence auxiliary participation. If they highlight incidents of civilian harm or economic disruption linked to foreign forces, they increase grievance. External narratives do not create insurgencies. They influence the momentum and direction of mobilization, which can affect how quickly resistance scales.

Sanctuary, Regeneration, and the Structural Advantages Available to Resistance Networks

Forms of Sanctuary and Their Role in Sustaining Resistance

Sanctuary is one of the strongest predictors of a resistance movements longevity because it allows undergrounds, auxiliaries, and armed groups to rest, reorganize, and reconstitute after setbacks. Sanctuary can take many forms. Physical terrain, sympathetic communities (Sadr City), weak state presence (Afghanistan), or cross-border mobility (Laos in Vietnam). Venezuela contains all four.

Physical sanctuary exists in mountainous regions, dense jungle, and river basins where state presence is limited. Social sanctuary exists in communities that maintain strong informal governance networks and where colectivos or criminal groups already exert authority. Administrative sanctuary arises when formal institutions lack the capacity to enforce control. Cross-border sanctuary is available along the Colombian, Brazilian, and Guyanese frontiers where longstanding illicit routes provide concealment and logistical support. These conditions create multiple layers of resilience that resistance groups can use when responding to foreign forces.

Cross-Border Mobility and the Colombia and Brazil Frontiers

The frontier with Colombia has supported decades of illicit activity involving smuggling networks, armed dissidents, and local facilitators. These actors know the terrain, maintain trusted cross-border channels, and possess relationships in communities on both sides of the border. Access to routes of withdrawal lowers the perceived risk of participation in insurgent activity because individuals believe they can escape harm if conditions deteriorate.

Along the Brazilian border, dense jungle limits state presence and surveillance. Armed groups can move through these areas with minimal detection. Such terrain allows resistance networks to disperse, regroup, and reemerge in new locations. Cross-border mobility does not guarantee organized resistance, but it does provide the survivability that allow fragmented groups to persist even if they lack sustained central leadership.

These frontiers would complicate any effort to isolate or dismantle resistance structures. Even small groups could regenerate repeatedly because sanctuary enables strategic patience and opportunistic engagement.

Maritime and Littoral Pathways as Secondary Sanctuary Networks

Venezuela’s Caribbean coastline includes fishing communities, isolated coves, and informal maritime traffic. These areas support small craft movement used for smuggling or migration. In an instability scenario, these routes could support auxiliary functions such as information transfer or the movement of small quantities of materiel or personnel.

Maritime sanctuary in Venezuela does not provide the equivalent scale of land-based sanctuary, but it does contribute to network resilience by offering alternative access points and routes. Resistance movements often rely on multiple small channels of support rather than a single dominant pathway. Redundancy increases adaptability and reduces vulnerability to disruption.

Urban Sanctuary and the Megacity as a Regenerative Environment

Caracas introduces a different type of sanctuary. Megacities create conditions where resistance networks can blend into dense populations and complex physical terrain. Large urban centers provide anonymity, diverse social networks, and physical concealment. Urban environments support clandestine activity because surveillance becomes increasingly difficult and movement patterns are harder to track. They provide ready-made channels for resistance groups to hide personnel, distribute resources, and gather information. Urban sanctuary allows groups to sustain themselves inside the operational space of foreign forces, which increases the difficulty of identifying and dismantling undergrounds or auxiliaries during stabilization efforts.

Resistance networks that possess both sanctuary and external support gain the ability to activate, withdraw, and reappear in cycles. These cycles shape conflict duration and influence population confidence in the movement. This dynamic increases the complexity faced by stabilization or counter-insurgent forces seeking rapid stabilization.

Brazil’s Criminal Militias: Expanding Power and Territorial Control

Al Jazeera English | YouTube · Published [Update Date]

Al Jazeera English examines the rise of armed criminal militias in Brazil, their consolidation of territorial control, and the implications for governance, public security, and irregular conflict dynamics.

How Sanctuary Shapes Resistance Tempo and Duration

Resistance networks that access sanctuary do not require constant engagement. They can conduct limited operations, assess the response of foreign forces, and adapt their strategy, it enables irregular groups to impose selective cost, thereby increasing uncertainty for intervention forces. This uncertainty influences the operational tempo and complicates predictions about escalation.

Venezuela’s combination of rural frontier sanctuary, maritime pathways, and megacity concealment gives potential resistance networks a mixture of environments for survival. Such a combination increases the likelihood that resistance would persist even if initial mobilization were fragmented or disorganized.

Resistance movements endure when sanctuary intersects with grievance, opportunity, and local leadership. Venezuela exhibits all of these conditions. It is the confluence of multiple intersecting, and mutually reinforcing elements that support a sustained resistance to both invasion, and occupation.

Novel Security Challenges in a Contemporary Counterinsurgency Environment

The Tactical Disruption Caused by sUAS Proliferation

Small unmanned aircraft systems (sUAS) have become a defining feature of modern irregular warfare. They provide low cost, precision effects to actors who previously lacked access to comparable capabilities. Disruptive technologies allow irregular groups to impose disproportionate cost on intervening forces. Venezuela contains many of the conditions that support rapid adaptation of commercial drones into military tools.

The widespread availability of consumer and enterprise drones creates a ready supply of platforms that can be repurposed for reconnaissance, target acquisition, and improvised strike missions. Armed groups and criminal networks already demonstrate technical familiarity with electronics, communications equipment, and modification of commercial systems. These skills form the foundation for an early shift toward sUAS-enabled resistance tactics.

Drones: A New Weapon for Colombia’s Guerrillas

FRANCE 24 English — YouTube · Published Jul 7 2025

FRANCE 24 English examines how Colombian guerrilla groups are adapting commercial drones for surveillance and attack roles, illustrating the evolving sUAS threat in contemporary insurgency.

sUAS- IED’s That Can Fly

The weaponization of commercial drones into flying improvised explosive devices is no longer limited to conflict zones in the Middle East or Eastern Europe. In September of this year, authorities in Colombia reported that a police Black Hawk helicopter was downed by a modified sUAS operated by a non state actor. This incident demonstrates that the technical threshold for producing a drone capable of delivering destructive effect has decreased and is already in theater.

In a hypothetical Venezuelan resistance environment, the combination of urban density, elevated terrain, narrow valleys, and fragmented neighborhoods would enable widespread employment of flying IEDs (sUAS). These systems can approach from unexpected angles, bypass checkpoints, and target vehicles, observation posts, or command nodes. Even when the destructive yield is low, the psychological and operational impact is significant. Irregular groups often exploit these effects to shape behavior, restrict movement, and disrupt stabilization operations.

Surveillance, Targeting, and the Democratization of Airborne Reconnaissance

Commercial drones provide resistance networks with accessible surveillance tools. Real time video, geolocation capability, and intuitive control interfaces mean that inexperienced operators can rapidly collect information on patrol routes, troop movements, and static positions. Information advantage as a major influencer of resistance confidence and when groups believe they possess superior awareness of intervening forces, recruitment increases.

In Caracas and other urban centers, drones can operate from rooftops, balconies, alleyways, and dense neighborhoods that complicate detection. The city’s topography, including the mountains that surround the capital, enable long distance observation of key approaches and staging areas. These factors reduce the ability of foreign forces to operate with predictability or maintain operational secrecy.

Limitations of Current Counter-UAS Capabilities in Dense Terrain

Counter-UAS technologies remain uneven in their effectiveness, especially in crowded electromagnetic environments. Most systems face challenges detecting low profile drones in cluttered airspace. Dense infrastructure creates radar shadows and signal reflections that degrade sensor performance. Urban environments also contain high volumes of legitimate radio frequency activity that reduce the clarity of detection.

Intervening forces would need to deploy layered counter-UAS capabilities ranging from handheld detectors to networked sensors and interdiction capabilities. Even with such measures, the volume of drones that could appear in a megacity the size of Caracas would create significant strain. Resistance movements exploit the limitations of superior forces by overwhelming their systems with low cost adaptations. sUAS proliferation is an example of this dynamic and US countermeasures have not been proven and are not yet a mature battlefield capability that is both reliable, cost adjusted, and scalable.

The Psychological and Operational Effects of Persistent Aerial Threats

Drones impose psychological pressure on both military personnel and civilians. Persistent overhead activity generates uncertainty about whether a platform is conducting reconnaissance or preparing a strike. This uncertainty influences the behavior of patrols, supply convoys, and civilian movements. Irregular groups use this uncertainty to exploit gaps in security and apply pressure disproportionately to their size.

The presence of drones also influences civilian perceptions. If resistance networks demonstrate the ability to operate drones effectively, civilians may believe these groups possess strategic depth or external support. Perceived capability influences decisions to join or assist resistance. Drones enhance perceived capability even when their destructive effect is limited.

The Adaptation Curve of Irregular Actors in Venezuela

Armed groups in Venezuela possess experience with improvised weapons, illicit communications, and distributed networks. These experiences reduce the time required for adaptation to drone use. They also enable rapid transfer of knowledge among groups. Criminal networks in Caracas and the borderlands have demonstrated the ability to modify weapons and electronic systems under resource constrained conditions. This adaptation pathway increases the likelihood that sUAS-enabled tactics would emerge early in a conflict scenario.

Foreign sponsors could accelerate adaptation by providing technical training, components, or guidance on employment. Even limited assistance can have significant impact because irregular groups often require only incremental improvements to generate disproportionate effect.

sUAS are positioned to reshape the tactical environment by granting resistance networks airborne reconnaissance, precision strike options, and psychological leverage. Venezuela’s terrain, urban density, and existing armed networks amplify these challenges.

Plausible Resistance Trajectories, and Stabilization Requirements

Plausible Resistance Behavior in a Foreign Intervention Scenario

The combination of population size, sanctuary availability, urban complexity, and armed network proliferation suggests that resistance in Venezuela would emerge in multiple, overlapping forms rather than through a single organized movement. Many Venezuelans already participate in paramilitary training or receive weapons through state aligned programs. Reporting shows distribution of arms to civilian defense groups, while others pursue independent preparation for instability. These activities form a foundation of latent mobilization that could activate quickly if foreign ground forces enter the country.

Resistance behavior would not remain static. Early resistance may begin as localized harassment by colectivos, neighborhood groups, or criminal entities seeking to assert territorial control. These actors could blend political motives with self preservation instincts as they reframe their identity in relation to foreign forces. Over time, disparate groups may converge or deconflict informally, creating a distributed but persistent irregular environment. This pattern is technically defined as a mosaic resistance structure where multiple nodes generate pressure without unified command.

Urban centers would experience rapid activation of low signature tactics. Armed sUAS, ambushes in narrow streets, sniper activity from dense vertical terrain, and targeted attacks on logistics nodes are plausible. Rural sanctuary areas would generate longer duration guerrilla activity drawn from dissident groups, criminal networks, or politically motivated actors. Even small groups could impose significant cost due to sanctuary, external support perceptions, and the difficulty of securing vast terrain.

Stabilization Requirements and the Challenge of Controlling a Large, Violent, and Fragmented Population

Stabilization requires more than presence. It demands control of terrain, population engagement, sustained intelligence collection, and political alignment. In Caracas alone, the scale of the challenge is daunting. A megacity of nine million people creates a population center larger than many countries and dense populations with fragmented governance structures increase the demand for force ratios far beyond typical counterinsurgency planning factors.

Venezuela has extremely high rates of violent crime including homicide and armed robbery. These indicators suggest a population familiar with violence as both a survival mechanism and a tool of coercion. Ted Robert Gurr explains that populations with established patterns of violent grievance expression adapt quickly to new forms of conflict. A large violent milieu increases the probability that irregular activity scales quickly once constraints weaken.

Criminal gangs can pivot into political or quasi political roles when foreign forces enter the environment. These groups may attempt to extract resources, control neighborhoods, or negotiate for autonomy. Some may collaborate with resistance networks either out of ideological alignment or pragmatic survival. Their preexisting organization, access to weapons, clandestine network architectures, and territorial control reduce the lead time needed to generate resistance actions.

Stabilization would require significant engagement in infrastructure repair, economic support, and population services. Any disruption in employment or education removes barriers to participation in resistance activity and individuals tend join movements when daily routines collapse and when informal networks provide alternatives. Venezuela’s economic conditions already lower these barriers, and foreign intervention could reduce them further unless stabilization efforts are immediate and large scale.

Theory of Victory and the Duration and Shape of Conflict

The theory of victory determines how forces design operations and how resistance emerges. A rapid regime decapitation followed by withdrawal creates one set of dynamics. If the stated goal is accurate, a cessation of illicit narcotics trafficking to the mainland US, this method is not likely to achieve the end state. A sustained stability operation designed to rebuild institutions creates another. Each pathway produces different incentives for resistance groups.

A limited strike or removal of key leadership without follow on stabilization resembles elements of the Libya model. Such an approach could create a vacuum that multiple armed groups seek to fill, resulting in fragmented conflict and persistent insecurity. This scenario would likely accelerate the activation of armed networks, empower criminal groups, and increase cross border sanctuary use.

A fully resourced stability operation resembles elements of Iraq and Afghanistan where large footprint forces engage in long term governance and security missions. This model reduces some forms of fragmentation but increases the duration of exposure to irregular attacks. It requires sustained political will, significant personnel, and large investments in reconstruction. In a country the size and complexity of Venezuela, these requirements scale dramatically. To be clear, it is measured in thousands of lives and hundreds of billions of dollars.

Irrespective of model choice, resistance networks respond to the perceived intentions and staying power of intervening forces. When populations believe a foreign force intends long term control or deep involvement in governance, resistance mobilization rises. If the foreign mission signals short duration presence, groups may accelerate activity to force early withdrawal or gain leverage in post conflict negotiations. Theory of victory therefore influences resistance tempo and strategic adaptation.

Synthesis of the Resistance Environment

Venezuela contains many of the structural features that support irregular conflict including a large population, high violence rates, preexisting armed groups, difficult terrain, megacity complexity, sanctuary access, and external political alignment that complicates stabilization. Resistance dynamics would likely be nonlinear, adaptive, and persistent.

Foreign forces entering Venezuela would face a mosaic resistance environment where multiple groups operate simultaneously, each with its own motives, capabilities, and territorial interests. Early stabilization challenges would stem from megacity conditions and the proliferation of flying IEDs, small drones, and criminal armed groups. Longer term challenges would emerge from rural sanctuary zones and cross border mobility.

Strategic Implications and the Irregular Warfare Risks Inherent in a Venezuela Intervention

Venezuela’s Structural Advantages in Irregular Conflict

Imperially, Venezuela presents a convergence of structural factors that favor effective prolonged insurgent activity. These factors include sanctuary, urban complexity, population size, high civilian exposure to violence, armed networks, and access to external sponsors. Venezuela contains each of these conditions in abundance, and enhanced by the physical environment.

The megacity of Caracas complicates every one of the seven warfighting functions: command and control, movement and maneuver, intelligence, fires, sustainment, protection and information. Rural and jungle areas create concealment and escape routes. River corridors support movement that bypasses fixed points of control. Mountainous terrain limits ground mobility and creates natural defenses. These features force occupation forces into fragmented operational approaches that resistance groups can exploit.

The Scale of Resistance Potential and Its Operational Consequences

A nation of more than twenty eight million people produces significant recruitment pools for both organized and ad hoc resistance activity. Chenoweth’s research on participation thresholds shows that even limited percentages translate into large numbers when the population scales into the millions. In the case of Venezuela, roughly three percent of the military-age male population equates to approximately 270,000 potential participants. This figure represents individuals who may not engage directly in armed action but could contribute through underground activity, auxiliary support, or information functions.

Venezuela’s high rates of violent crime mean that a portion of the population already has exposure to weapons, coercion, and survival driven violence. And individuals accustomed to violent environments face lower psychological thresholds for lethal participation. Armed networks, colectivos, and criminal groups provide ready made organizational structures that can orient against an invader. Foreign forces entering this environment would encounter resistance networks that require almost no time to activate.

External Actors and the Expansion of Operational Risk

External actors amplify the difficulties of intervention. Cuba, Russia, Iran, and China have political and strategic motives to influence events in Venezuela. These states do not require formal alliances to shape the conflict. Their support in intelligence, information operations, technology, and political messaging can increase the resilience of resistance networks or encourage prolonged conflict.

Large scale U.S. force commitment in South America creates opportunities for strategic competitors. China benefits when the United States diverts significant resources away from the Indo-Pacific. Russia and Iran benefit when U.S. political and military bandwidth becomes strained. These incentives increase the likelihood that external actors would take steps to extend conflict duration. ARIS research on countering irregular warfare shows that conflicts with external stakeholders often experience longer timelines and higher operational cost.

The Technological Disruption of Stabilization Efforts

sUAS proliferation magnifies Venezuela’s irregular warfare potential which is further amplified by Russian, Chinese, and Iranian support. Counter-UAS systems remain uneven in performance and present significant challenges in urban environments. Baseline asymmetric toolsets have already surpassed two decades of COIN lessons learned. Any occupying force would be starting at zero in terms of stabilization force protection.

The Limits of Traditional Stabilization Frameworks

Traditional stability operations rely on securing the population, controlling key terrain, restoring essential services, and building institutions. Venezuela stretches each element of this framework. Caracas alone requires extraordinary personnel to maintain order. High levels of violent crime mean that stabilization forces must address both politically motivated resistance and baseline criminal activity. Rural sanctuary zones require parallel campaigns that focus on mobility, surveillance, and persistent presence.

Pre-existing economic collapse reduces the effectiveness of typical reconstruction incentives. Populations require credible pathways to improved living conditions before cooperation becomes durable. In Venezuela, economic recovery requires large scale investment and sustained governance capacity. Short duration interventions offer little opportunity to reshape these variables, which limits the likelihood of rapid stabilization. US COIN doctrine, outlined in FM 3-24 is largely based on the theory and practice of David Galula, which was predicated on a return to French colonial rule, not a return to self governance.

Why Venezuela Represents a Unique Irregular Warfare Challenge

Venezuela is not the largest country to face insurgency, nor the poorest, nor the most politically isolated. Its significance stems from the intersection of multiple high impact variables. It poses a potential irregular warfare environment that is unusually complex. Any foreign intervention must account for extreme challenges. The relative scarcity of traditional military targets means that Venezuelan irregular forces would rely heavily on asymmetric methods to deplete an occupiers domestic will. In terms of doctrinal typology it would probably fall along Maoist Insurgency lines. This dynamic increases the cost and duration of operations for intervening forces.

Any intervention in Venezuela must account for the likelihood that irregular warfare, more so than conventional confrontation, would define the operational and strategic experience. Decapitation and withdrawal is unlikely to achieve stated goals reduction in narco-trafficking, and stability would require a sustained effort, huge costs in blood and treasure, not to mention long term political will. The challenges extend beyond tactical engagement. They shape the probability of achieving strategic aims and the cost associated with them.

How This Assessment Was Conducted

This assessment draws entirely from open-source information and established academic research. Demographic data was taken from the U.S. Census Bureau International Database, the CIA World Factbook, and UN population estimates. Crime and violence trends rely on UNODC reporting, Venezuelan observatories such as OVV, and regional human-security datasets. Terrain analysis is informed by NASA EarthData, SRTM topography, and published environmental studies on the Guiana Shield and coastal mountain ranges. Research on resistance participation thresholds references civil resistance scholarship. Insights regarding illicit networks, armed groups, and cross-border activity incorporate ACLED reporting, independent fieldwork summaries, and regional security analyses from academic and NGO sources. No classified material was used.

2. Limitations of the Assessment

This analysis is constrained by several factors. Migration outflows and internal displacement make Venezuelan demographic estimates inherently unstable. Crime statistics vary widely due to underreporting, political pressure, and inconsistent data collection. Terrain assessments rely on remote sensing and published studies rather than on-the-ground surveys, which limits fidelity in micro terrain representation. The behavior of armed groups, political factions, and civilian networks in crisis conditions is difficult to predict from open sources. This assessment models potential outcomes rather than probabilities and does not claim to forecast actual resistance behavior or military results. The analysis is based solely on publicly available information and serves as a conceptual framework for understanding risk and resistance potential.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply