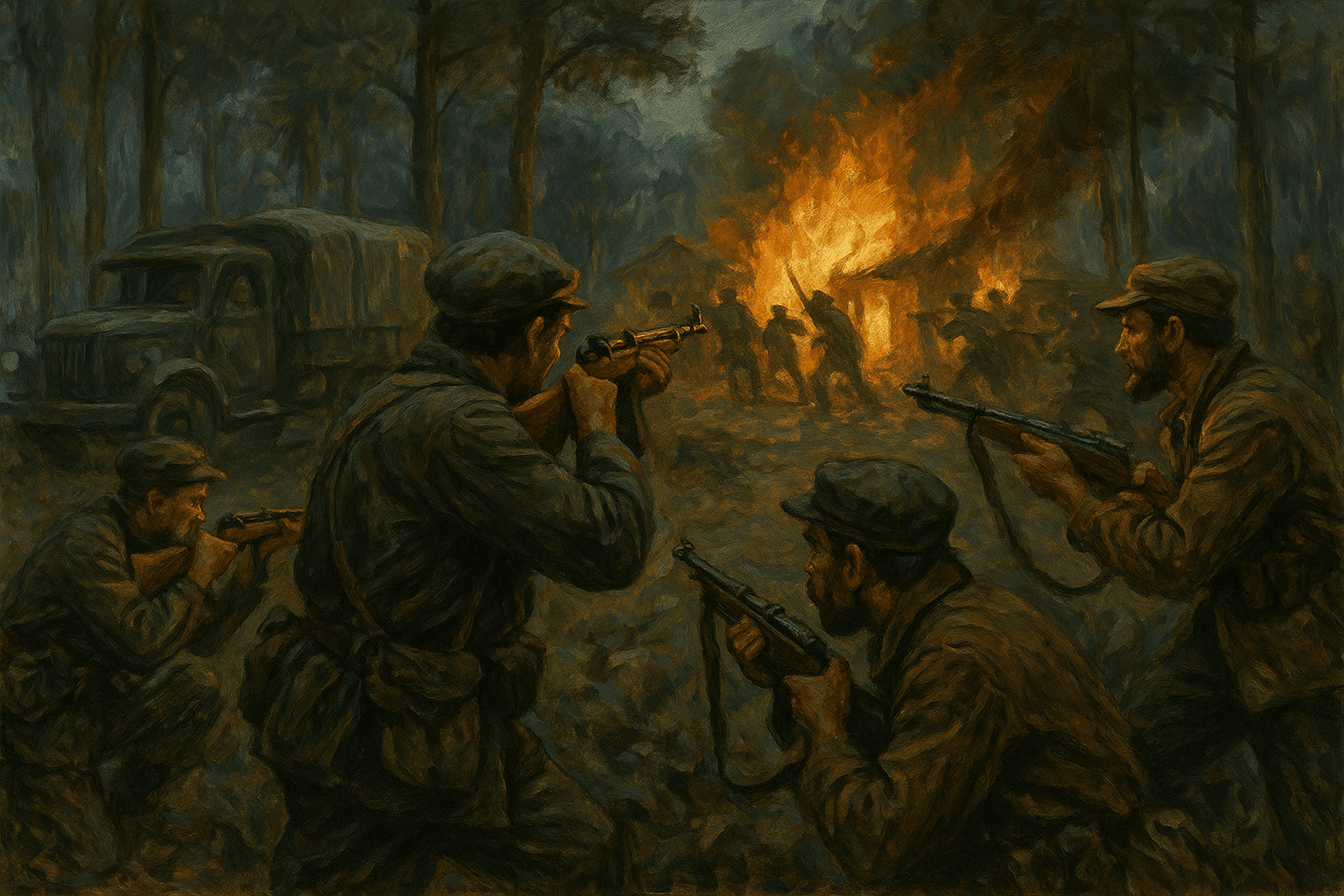

The Guerrilla Raid: Precision, Pressure, and Psychological Impact

Guerrilla warfare depends on deception, mobility, and asymmetry. Few tactics embody these principles more clearly than the raid. When executed well, a raid can cripple enemy logistics, disrupt command nodes, and deliver a psychological shock that far exceeds its physical damage. But when executed poorly? A failed raid is one of the quickest paths to strategic failure in any insurgency.

Historically, partisan fighters and guerrilla movements have used raids to punch above their weight. From the jungles of Vietnam to the contested cities of South America, irregular forces have struck hardened targets and, in some cases, shifted the trajectory of an entire conflict. These operations are often fast, focused, and fleeting—designed to exploit weak points, not hold ground.

What separates a successful raid from a disastrous one? This article explores that question by analyzing the anatomy of the guerrilla raid. Drawing from real-world case studies and the lessons of both victory and defeat, we unpack what makes these operations effective—and where they often go wrong.

The Fundamentals of a Guerrilla Raid

A raid is not an ambush. Ambushes are reactive, designed to trap enemy forces as they pass through a predetermined location. Raids, by contrast, are proactive. They strike a specific target, achieve a focused objective, and withdraw before the enemy can organize an effective response.

To succeed, a guerrilla raid must adhere to four core principles:

Speed and Surprise

Raids depend on shock. The target must be caught off guard, with no time to react. Guerrilla fighters exploit unpredictability, striking when and where the enemy least expects. Without surprise, defenders can mobilize, forcing a prolonged engagement—a scenario that irregular forces must avoid at all costs.

Intelligence and Planning

Accurate intelligence makes precision possible. Successful raids are built on detailed reconnaissance, a firm grasp of terrain, enemy defensive posture, and escape routes. Without this foundation, guerrilla units risk hitting a hardened target—or missing key vulnerabilities altogether. See our guide on reconnaissance operations for more on this vital preparatory step.

Achievable Objectives

A realistic objective reduces the chance of mission failure. Guerrilla forces operate with limited manpower, weapons, and time. Targets must be carefully selected to deliver maximum disruption without exceeding operational limits. Overreach often ends in disaster, as seen in several failed sabotage campaigns.

Rapid Withdrawal

The exit plan matters as much as the attack itself. Guerrilla units rarely have the strength to sustain a prolonged fight. A successful raid strikes fast, causes disruption, and disappears before the enemy can mount a counterattack. This principle is critical to the long-term survivability of irregular networks.

When these principles align, even a small, lightly armed force can achieve disproportionate results. Raids can sever supply lines, eliminate high-value targets, or destroy critical infrastructure with strategic precision. But when these fundamentals are ignored, the consequences are often severe—and permanent.

Theorists on Guerrilla Raids

Guerrilla raids are not mere acts of improvisation. They are deeply rooted in irregular warfare theory, refined by some of history’s most influential thinkers. These strategists didn’t just endorse raids—they embedded them within broader doctrines of resistance, revolution, and protracted conflict.

T.E. Lawrence: Raids as Force Multipliers

T.E. Lawrence, famed for his role in the Arab Revolt, argued in Seven Pillars of Wisdom that raids were not only tactical tools but strategic levers. Operating in vast desert terrain, Lawrence saw raids as a way to magnify the impact of small, mobile units. Rather than directly confronting Ottoman forces, his fighters struck rail lines, supply depots, and key bridges—undermining the enemy’s ability to operate and respond. These raids were not about annihilation but erosion: wearing down a superior enemy by denying them freedom of movement and logistical certainty. His legacy continues to influence modern guerrilla doctrine, especially in environments where mobility and surprise can overcome raw firepower.

Che Guevara: Sustaining Revolutionary Morale

For Che Guevara, raids held psychological and symbolic power. In Guerrilla Warfare, he emphasized that even limited attacks could produce outsized morale effects—on both sides of the fight. A successful raid, no matter how minor, could lift the spirits of insurgents and demonstrate the vulnerability of the regime. Guevara’s approach was revolutionary in both form and intent: raids were not just disruptive, but energizing. They served as proof-of-concept for rebellion, showing that resistance was viable. This focus on morale and mobilization became central to Latin American insurgencies throughout the 20th century.

Vo Nguyen Giap: Strategic Raiding in Protracted War

Vo Nguyen Giap, chief military strategist of the Viet Minh and later the North Vietnamese Army, integrated raids into a long-term strategy of attritional warfare. Unlike Guevara’s emphasis on symbolic gains, Giap orchestrated raids as part of coordinated campaigns. These operations targeted French and American forces alike, weakening outposts, cutting supply routes, and undermining morale ahead of larger offensives. Giap understood that no single raid would win the war—but their overall effect could shift the balance of power. This philosophy, blending strategic patience with tactical aggression, helped turn Vietnam into one of the most studied resistance campaigns in modern military history.

Mao Zedong: Raids as Tools of Protracted Struggle

In On Guerrilla Warfare, Mao Zedong positioned raids within a doctrine of “protracted people’s war.” He saw them as deliberate tools of attrition, designed to stretch enemy supply lines, exhaust their forces, and sap their will. Mao’s vision was neither short-term nor symbolic—it was structural. Raids allowed his guerrillas to impose constant pressure on better-equipped opponents, while gradually building popular support and political infrastructure. His three-phase model of insurgency—organization, expansion, and decisive engagement—relied heavily on the ability to conduct effective raids during the middle phase. Mao’s teachings remain essential in resistance movements worldwide.

Michael Collins: Urban Raids and Asymmetric Assassination

Michael Collins revolutionized the use of raids in urban environments during the Irish War of Independence. Unlike rural-based insurgents, Collins operated in the heart of Dublin, where civilian terrain masked his network. His small assassination teams—such as The Squad—targeted British intelligence officers and collaborators with surgical precision. These urban raids sowed fear, disrupted counterinsurgency efforts, and forced the British government into political concessions. Collins proved that raids were not limited to jungles or mountains—they could be equally effective in cities, especially when coordinated through a clandestine network.

Orde Wingate: Deep-Penetration Raids in Conventional Warfare

Orde Wingate, best known for leading the Chindits in Burma during World War II, introduced a new dimension to raiding: deep-penetration operations behind enemy lines. His units—small, self-sufficient, and highly mobile—attacked Japanese supply nodes, railways, and communication hubs far from the front. Wingate’s raids forced enemy commanders to divert entire divisions to rear-area defense, tying down resources that would otherwise reinforce the main effort. Though his methods were controversial, Wingate demonstrated how raiding could serve not just irregular forces, but conventional militaries looking to achieve strategic disruption. His legacy echoes in modern special operations doctrine.

Each of these figures shaped how raids are planned, executed, and understood. Their contributions remain essential reading for anyone seeking to understand guerrilla tactics—not as stand-alone events, but as elements of larger strategic visions.

Case Studies of Effective Guerrilla Raids

Guerrilla raids are not random acts of violence—they are deliberate, planned operations designed to strike high-value targets with precision, then withdraw before a counterattack can form. These raids can disrupt supply lines, degrade morale, neutralize critical assets, or demonstrate the viability of a resistance movement. When integrated into broader campaigns, their strategic effects often far exceed their tactical scale.

The following case studies examine three guerrilla raids across varied environments—occupied France, the jungles of Indochina, and the streets of Dublin. Each one illustrates a core principle of irregular warfare: intelligence-driven targeting, strategic integration, and urban execution under clandestine conditions.

Objective: Destroy an electrical transformer station in Pessac, France, to cripple power to German U-boat bases on the Atlantic coast.

Outcome: The station was destroyed with no casualties. German naval operations were disrupted.

Key Principle: Precision through intelligence and local collaboration.

1. Operation Josephine B (1942) – French Resistance Sabotage

Strategic Sabotage in Occupied France

Operation Josephine B remains one of the most effective acts of sabotage carried out by the French Resistance in coordination with the British Special Operations Executive (SOE). The target: a transformer station in Pessac, which supplied electricity to multiple German U-boat facilities along the Atlantic coast. These naval bases were a linchpin in the Battle of the Atlantic, where German submarines sought to cut off Britain’s maritime lifelines.

Rather than risk a conventional assault, the staff focused on a small-team raid. The operation was designed to deliver maximum effect with minimal exposure—striking infrastructure, not personnel. This fit the broader Allied strategy of empowering local networks to degrade German capabilities behind the front lines.

Intelligence-Driven Targeting and Execution

The mission’s success hinged on precise intelligence and deep local knowledge. Resistance fighters and SOE operatives conducted weeks of reconnaissance, observing guard routines, mapping the facility, and identifying security gaps. They noted structural vulnerabilities and confirmed when the transformer station was least protected.

When the raid was launched, the team infiltrated the site silently, planted shaped charges on key components, and withdrew before dawn. There was no firefight. No alarms. Just calculated sabotage—followed by a delayed detonation that plunged multiple U-boat facilities into darkness.

Operational Impact and Lasting Lessons

The aftermath was significant. German engineers were forced to reroute electrical supply, reassign personnel, and harden similar sites throughout occupied France. In military terms, the raid imposed a logistical tax on the occupier—a classic guerrilla goal. In strategic terms, it degraded enemy capacity without provoking massive retaliation.

More importantly, Josephine B became a proof-of-concept for Allied support to indigenous resistance networks. It showcased what could be achieved through careful planning, cross-border collaboration, and local initiative. These lessons echo today in modern discussions of irregular infrastructure attacks and network-enabled resistance.

2. The Viet Minh Raid at Dong Khe (1950) – Tactical Mastery in Vietnam

Objective: Overwhelm a French outpost to cut off reinforcements and disrupt regional control.

Outcome: The outpost was quickly overrun, isolating other French positions and triggering a broader collapse.

Key Principle: Raids must be part of a larger strategic campaign—not isolated strikes.

Raiding as a Strategic Tool in the First Indochina War

The First Indochina War pitted French colonial forces against the Viet Minh, a nationalist and communist-led insurgency under General Vo Nguyen Giap. While the Viet Minh were often outgunned and undersupplied, they mastered the art of guerrilla warfare, using raids not as one-off attacks but as levers within broader strategic efforts.

One of the most illustrative examples is the raid on the French outpost at Dong Khe in 1950. Located in a remote but strategically vital region near the Chinese border, Dong Khe anchored the French defensive line in northern Vietnam. By targeting this position, Giap aimed to collapse the French perimeter and open a corridor for expanded Viet Minh operations.

The raid was not a standalone action—it was part of a coordinated campaign known as the Battle of Route Coloniale 4, designed to isolate, encircle, and defeat French units strung along a vulnerable supply line.

Precision, Preparation, and Local Dominance

Rather than launch a hasty frontal assault, the Viet Minh gathered intelligence on French patrol patterns, defensive layouts, and resupply routes. Local knowledge and population support allowed them to move undetected through the dense terrain. Giap’s forces surrounded the outpost and launched a coordinated assault in waves, supported by indirect fire and sappers breaching the perimeter.

Within hours, Dong Khe fell. But the real success was what followed. French attempts to send reinforcements were anticipated and ambushed along the surrounding jungle roads. These follow-on attacks enhanced the raid’s effect, turning a tactical win into a cascading strategic failure for the French.

The operation also allowed the Viet Minh to seize valuable equipment, including mortars and radios, and use the momentum to pressure adjacent French positions. The victory at Dong Khe signaled a turning point: French control in the north was no longer secure, and Giap’s strategy of encirclement and attrition had proven effective.

Strategic Integration and Campaign-Level Effects

What made Dong Khe notable was not just the speed or success of the initial raid—it was how it fit into a long-term plan to grind down French capabilities. Giap understood that isolated raids, no matter how successful, could not win the war. But when linked to broader campaign objectives, raids could serve as pressure points that disrupted logistics, undermined morale, and degraded an occupier’s ability to project power.

The raid also reflects core lessons for modern irregular warfare:

- Strike where the enemy is stretched thin.

- Use terrain and local support to your advantage.

- Ensure every tactical action supports a strategic aim.

Dong Khe ultimately sped up the unraveling of the French position in northern Vietnam and foreshadowed the long, grinding campaigns that would define Vietnamese guerrilla doctrine for decades to come.

3. Michael Collins and the Dublin Raid Teams – Urban Guerrilla Warfare Refined

Objective: Disrupt British intelligence operations through targeted assassinations in the urban core.

Outcome: British counterinsurgency efforts were severely hampered; morale and operational capacity declined.

Key Principle: Raids can thrive in urban terrain when supported by clandestine networks and precise targeting.

Urban Resistance in the Heart of the Empire

While guerrilla warfare is often associated with jungles or rural hideouts, Michael Collins demonstrated that cities could be just as fertile a battleground. During the Irish War of Independence (1919–1921), Collins—then Director of Intelligence for the Irish Republican Army (IRA)—assembled a network of clandestine operators in Dublin capable of executing high-impact, low-visibility raids against British personnel.

At the core of this effort was “The Squad,” a hand-selected unit of IRA fighters trained to conduct assassinations and sabotage missions in broad daylight. Their targets were not random soldiers but intelligence officers, informants, and key enablers of British rule. These raids were surgical—designed not only to eliminate individuals, but to paralyze the broader intelligence apparatus that enabled counterinsurgency.

One of the most famous examples was the series of coordinated assassinations carried out on Bloody Sunday (21 November 1920), when Collins’ network struck multiple British intelligence officers across Dublin in a single morning.

Network-Enabled Targeting and Escape

The success of these urban raids was due less to firepower than to network design. Collins operated a layered system of safe houses, informants, runners, and couriers that enabled his units to strike and disappear—often within blocks of heavily guarded British buildings. Urban density gave the IRA both concealment and complexity: escape routes were abundant, and British forces struggled to distinguish guerrilla fighters from civilians.

These raids required precision and discipline. Targets were surveilled for weeks, routines memorized, weapons cached nearby. The goal was to strike decisively and escape cleanly—not to fight extended battles. When successful, each raid sowed fear, degraded British morale, and forced increasingly draconian responses that alienated the local population.

For the British, the psychological toll was immense. Officers lived under constant threat, unsure whether the bartender, driver, or tailor might be an IRA operative. For the IRA, these attacks proved that even in the heart of the empire’s capital, resistance was possible—and effective.

Strategic Effects Beyond the Bullet

Collins understood that assassinations alone would not win the war. But as a tool within a broader campaign of political and military pressure, raids allowed the IRA to seize initiative and shape the narrative. British intelligence was eventually forced to scale back operations in Dublin, reassign officers, and invest in defensive measures that drained time and resources.

Importantly, these raids had strategic effects disproportionate to their scale. They disrupted the flow of intelligence, denied the British regime the ability to operate with impunity, and created space for parallel political efforts that would ultimately lead to a negotiated truce.

Today, Collins’ urban operations offer enduring lessons for modern resistance movements:

- Cities are not obstacles to guerrilla operations—they are opportunities.

- Intelligence, not firepower, determines success.

- Strategic targeting can generate both operational disruption and political leverage.

This model has since been copied in resistance movements from Algeria to South Africa to occupied Ukraine, proving that even under tight surveillance, urban raids remain one of the most survivable and effective tools of asymmetric warfare.

Final Thoughts

These guerrilla raids demonstrate the core principles of effective irregular warfare: actionable intelligence, achievable objectives, and integration within broader strategic efforts. Raids are not random strikes—they are deliberate operations designed to shape the battlefield and pressure stronger adversaries into overextension.

Operation Josephine B shows how sabotage—when guided by local knowledge and precise targeting—can deliver strategic effects with minimal force. The destruction of a single transformer station forced Germany to divert resources and tighten rear-area security.

The Viet Minh Raid at Dong Khe highlights how tactical success gains value when tied to larger campaigns. The fall of this outpost set off a chain reaction, weakening French control across northern Vietnam and validating the role of raids in long-term attritional warfare.

Michael Collins’ urban operations in Dublin reveal the power of small-unit raids in dense environments. Supported by clandestine networks, these targeted assassinations crippled British intelligence and shifted momentum toward the resistance.

Each case reinforces a key truth: guerrilla raids are not just about destruction—they’re about disruption, decision-making pressure, and creating space for broader resistance efforts. Whether in occupied cities or contested jungles, raids remain among the most effective tools in the asymmetric warfare toolkit.

Case Studies of Ineffective Guerrilla Raids

While guerrilla raids can be effective when executed properly, history offers just as many cautionary tales. Failed raids often stem from poor intelligence, overconfidence, internal leaks, or misreading the enemy’s response capability. These failures provide valuable lessons, exposing the risks of operational overreach and doctrinal misalignment.

The following three case studies reveal how guerrilla operations can falter when fundamentals are ignored. From Chechnya to South America, these examples highlight tactical and strategic breakdowns that ultimately cost insurgent groups both force strength and momentum.

Chechen Raid on Grozny Rail Terminal (1995) – Urban Failure Under Fire

Objective: Disrupt Russian troop and supply movements by seizing a major rail hub.

Outcome: Russian forces encircled the raiding team, killing or capturing most of the fighters.

Key Principle: Urban raids require exit plans and population support—without both, collapse is inevitable.

Poor Timing, Poor Cover

In late 1995, during the First Chechen War, a group of Chechen fighters launched a raid on the Grozny rail terminal—a strategic hub for Russian troop and supply movements. The operation aimed to disrupt logistics and force a public relations crisis for the Kremlin. However, the raid unfolded in broad daylight and lacked local concealment. The surrounding area, once sympathetic, had been largely evacuated or pacified, leaving little civilian cover.

The fighters entered the rail yard expecting minimal resistance but were instead met with armored units and entrenched Russian infantry. Intelligence had failed to detect that the terminal had recently been reinforced in response to earlier guerrilla attacks elsewhere in the city.

Consequences and Lessons

Encircled and without viable exfiltration routes, the raiders found themselves in a prolonged urban firefight—a scenario guerrilla doctrine explicitly warns against. Russian forces used superior firepower and interior lines to crush the assault. Few guerrillas escaped.

This failed operation cost the Chechens key personnel and gave Russian forces a propaganda win. It also revealed the limitations of urban raids when they are not backed by local intelligence, mobility corridors, or support from the clandestine population base. The Grozny rail raid serves as a stark reminder that in modern cities, visibility equals vulnerability.

The Tupamaros Raid on the Montevideo Bowling Club (1971) – Urban Guerrilla Overreach

Objective: Capture military officers for a prisoner exchange.

Outcome: The guerrillas walked into a government trap and were neutralized.

Key Principle: Never underestimate enemy counterintelligence.

Tactical Precision Undone by Infiltration

The Tupamaros, a Marxist urban guerrilla group operating in Uruguay during the 1960s and early 1970s, gained notoriety for daring raids, bank robberies, and high-profile kidnappings. In 1971, they targeted the Montevideo Bowling Club, a venue frequented by military officers. Their goal was to seize hostages for leverage in prisoner negotiations.

Unbeknownst to them, Uruguayan intelligence had infiltrated their ranks and learned the details of the planned operation. The raid began as scheduled—but instead of catching military officers by surprise, the Tupamaros encountered well-positioned security teams and police reinforcements.

Collapse of Operational Trust

The resulting gunfight led to multiple deaths and arrests, decimating the unit involved and undermining the credibility of the organization’s leadership. Worse, the failed raid gave the government a propaganda victory, portraying the Tupamaros as reckless and weakened. Public sympathy waned, and urban support networks began to erode.

This case highlights the critical importance of counterintelligence awareness. Guerrilla groups must constantly vet their members, rotate plans, and assume surveillance is active. One compromised operation can cost years of trust, capability, and narrative control.

FARC Raid on Miraflores Military Base (1998) – Tactical Overconfidence

Objective: Overrun a Colombian Army base and seize weapons.

Outcome: The Colombian military repelled the attack, inflicting heavy losses.

Key Principle: Without secrecy, raids become frontal assaults—and usually fail.

From Guerrilla Strike to Conventional Defeat

At the height of its power, the Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) attempted to transition from guerrilla harassment to strategic-level assaults. In 1998, it launched a massive raid against the Miraflores military base in southern Colombia. The goal was to overwhelm the outpost, seize its armory, and deliver a symbolic blow to the state.

However, the government had intercepted communications and was forewarned. As the FARC columns approached, air assets, artillery, and reinforcements were mobilized. The raiding force walked into a kill zone. What began as a high-risk raid devolved into a bloody rout.

Operational Overreach and Its Consequences

The FARC suffered major losses, both in personnel and in momentum. The defeat damaged its image as an unstoppable insurgent force and emboldened Colombian security forces to escalate counterinsurgency efforts. The operation also exposed fractures in FARC’s command and control—some elements advanced too early, while others withdrew without orders.

This failed raid reinforces the timeless guerrilla principle of operational secrecy. Once surprise is lost, even a numerically superior force may be undone by well-prepared defenders. Ambition without security turns raids into disasters.

Tactical and Strategic Considerations

A failed raid is not merely a tactical setback—it can have cascading effects across a guerrilla campaign. It hurts more than one moment. It can spread doubt, fear, and confusion through a group. Understanding both the strategic utility and operational risks of raids is essential for any irregular force seeking to survive and succeed against a superior adversary. These risks must be studied, taught, and remembered. Clear thinking, solid planning, and strong teamwork are what give raids their strength. When those are missing, even the best fighters may lose.

Strategic Value of Guerrilla Raids

They degrade enemy morale

A successful raid sows distrust and fear among occupying forces. By demonstrating reach and unpredictability, it forces the enemy to question their security, often leading to operational hesitation and internal friction. The psychological toll of repeated attacks can be as damaging as physical losses.

They disrupt logistics and momentum

A well-timed raid targeting a bridge, rail line, or fuel depot can sever supply chains and degrade tempo. These disruptions force enemy forces to divert manpower to defensive tasks, slowing offensives and fracturing command rhythms.

They deliver disproportionate effects with limited resources

Raids are among the most cost-effective tools in asymmetric warfare. A small team of trained guerrillas can destroy critical infrastructure or eliminate high-value targets—outcomes that would require entire battalions in conventional warfare.

Operational Risks and Tradeoffs

The enemy adapts

Raids that follow predictable patterns invite countermeasures. Fortified sites, quick-reaction forces, and persistent surveillance all emerge in response. Tactical innovation and unpredictability are critical to staying ahead of an evolving opponent.

Failures erode credibility and support

A botched raid can demoralize fighters, damage recruitment efforts, and alienate the civilian population. Local supporters may hesitate to assist guerrillas if they associate them with reckless or failed actions—especially when reprisals are likely.

Overconfidence breeds mission creep

Effective raids can tempt guerrilla leaders into scaling up operations beyond their capacity. What begins as precision targeting can escalate into prolonged engagements with unsustainable casualties. Knowing when to strike—and when to disengage—is a key aspect of strategic resistance planning.

Final Lessons from Failed Guerrilla Raids

The lessons drawn from failed guerrilla raids are clear: irregular warfare demands more than courage and firepower. It requires precision, discipline, and a ruthless commitment to truth over assumption. Most failures in guerrilla history are not due to enemy strength—but to internal errors in planning, intelligence, or judgment.

While we replaced the original example, raids like the Tupamaros’ failed operation in Montevideo and the FARC’s disastrous assault on Miraflores underscore the same truth: without secrecy, intelligence, and adaptability, even seasoned guerrilla forces are vulnerable to collapse.

These are not just historical lessons—they are operational imperatives for today’s irregular actors. As surveillance tightens and counterinsurgency tools evolve, the margin for error in raids has grown thin.

How Should Modern Raids Adapt

The message for modern resistance movements and special operations forces alike is simple:

- Never raid without verified intelligence.

- Never underestimate the enemy.

- Never sacrifice adaptability for ambition.

History has shown that a single failed raid can unravel years of progress. But a well-planned, precisely executed raid—however small—can shift the course of a campaign. Raids are powerful not because they destroy the most, but because they hit where it hurts. They can shake the enemy’s mind, stop their supplies, and force them to act in fear. One good raid can inspire people, build trust, and show that resistance is still alive. It tells others that the fight is not over. Even small groups can make a difference. That is the power of clear goals, good planning, and quiet moves. In guerrilla war, smart actions matter more than big ones.

Culminating Lessons: Raids as the Edge of Irregular War

Guerrilla raids have long served as a tactical scalpel in irregular warfare—sharp, precise, and devastating when used correctly. Whether executed in the mountains of Vietnam, the streets of Dublin, or the jungles of Colombia, the best raids share common traits: speed, actionable intelligence, achievable objectives, and strategic alignment.

But these operations are not without risk. History offers just as many cautionary tales as triumphs. Failed raids—such as the Tupamaros’ ambush at the Montevideo Bowling Club or the FARC’s catastrophic assault on Miraflores—underscore how overconfidence, poor planning, or compromised secrecy can unravel years of effort. A single botched mission can disrupt networks, erode public support, and shift the strategic initiative back to the occupying force.

The true value of a raid lies in disruption with purpose. Raids are not about destruction alone—they are about denying the enemy time, space, and freedom of action. They force stronger forces into defense, dilute their focus, and buy time for insurgents to maneuver or regroup.

For modern resistance movements and special operations forces, the lessons are enduring: strike with intelligence, withdraw with precision, and always embed tactical actions within a broader campaign.

In an era of hybrid threats and digital surveillance, the fundamentals of the guerrilla raid remain unchanged. Learn from history. Adapt the method. Never raid without a reason—or a plan to disappear.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply