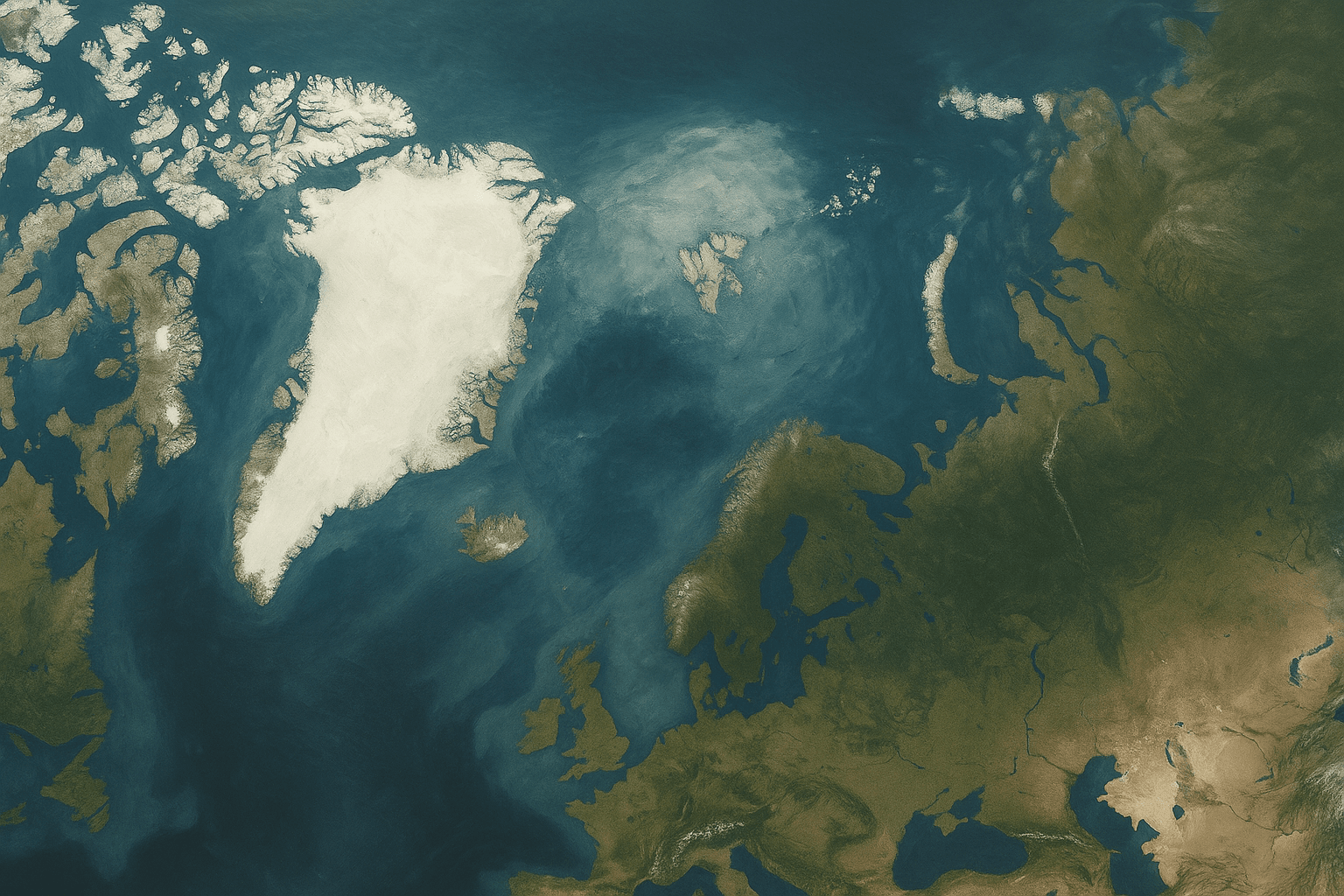

The Arctic was once dismissed as a frozen frontier. For centuries, thick ice and harsh conditions kept the region isolated from global competition. That insulation is disappearing. Climate change has reduced sea ice cover, making the High North more accessible than ever before.

New shipping routes such as the Northern Sea Route along Russia’s Siberian coast and the Northwest Passage across Canada are now navigable for longer periods each year. These corridors shorten the distance between Asia, Europe, and North America. For global trade and military mobility, that advantage is significant.

The Arctic also holds vast reserves of oil, natural gas, rare earth minerals, and fisheries. Control over these resources and the infrastructure that supports them has become a strategic priority. Russia views Arctic dominance as central to its great-power status. China, branding itself a “near-Arctic state,” has utilized research programs, shipping investments, and diplomatic pressure to assert its claim. NATO allies, Norway, Finland, Denmark (via Greenland), and Canada—see the region as a defensive flank that cannot be ignored.

Yet this competition is not limited to icebreakers and submarines. Irregular warfare in the Arctic is already visible. Russia employs hybrid tactics such as electronic warfare, cyberattacks, and covert maritime activity. China blends scientific research with intelligence collection. Civilian actors, fishing fleets, indigenous communities, and shipping firms are increasingly caught in the middle.

The High North is no longer an untouched wilderness. It is a contested arena where sabotage, disinformation, and resilience matter as much as conventional military power. Understanding these irregular dynamics is essential to grasping the future of Arctic security.

Russia’s Hybrid Strategy in the High North

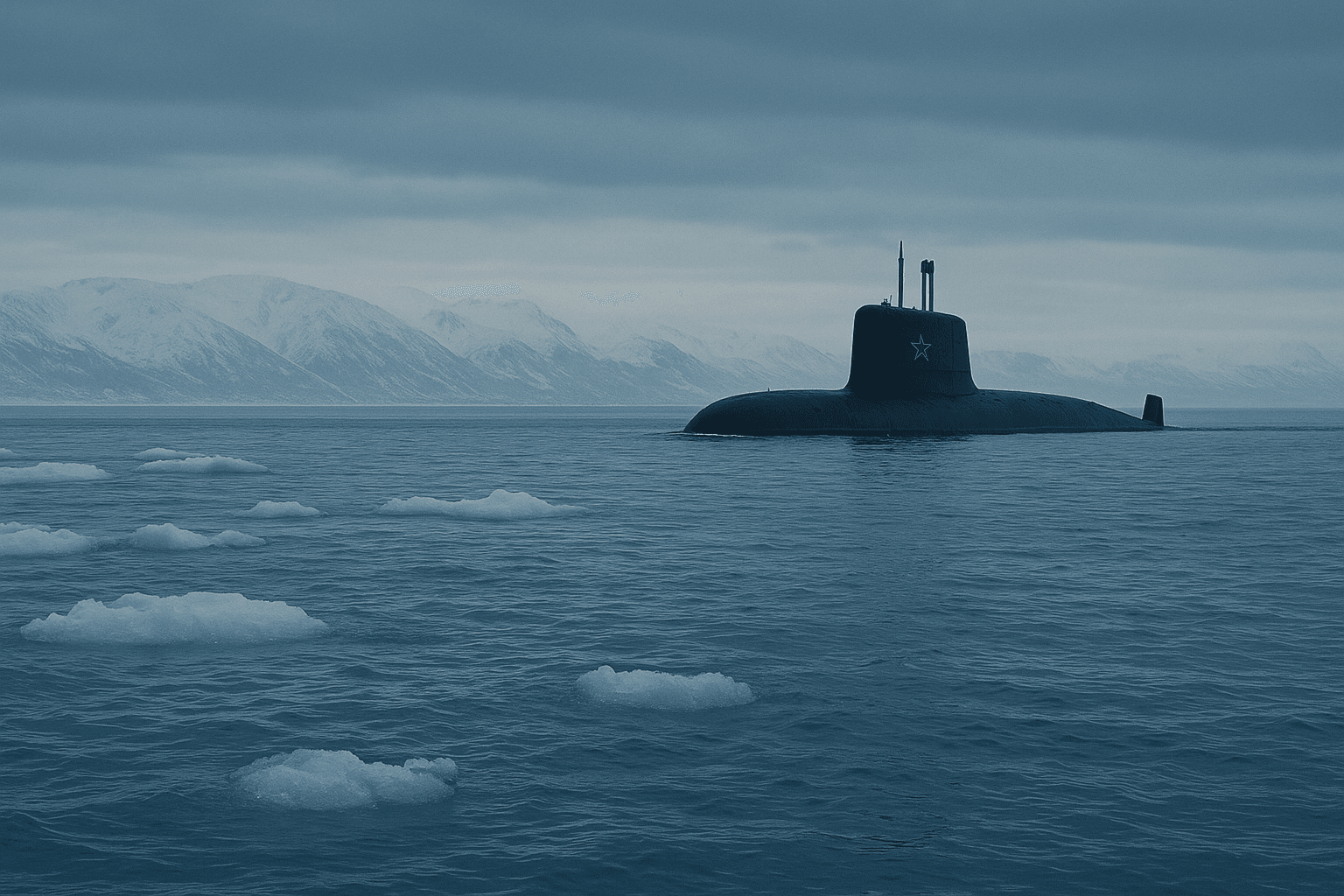

The Northern Fleet as a Strategic Anchor

Russia holds the largest and most capable military presence in the Arctic. The Northern Fleet, headquartered on the Kola Peninsula near Murmansk, is the centerpiece. It fields ballistic missile submarines, nuclear-powered icebreakers, and Arctic-trained brigades. For Moscow, the High North is both a shield for its nuclear deterrent and a lever of global influence.

GPS Jamming and Electronic Warfare

Russia’s most effective tools in the Arctic are hybrid operations that blur the line between peace and war. One such tool is GPS jamming. Pilots flying near Kirkenes in Norway or Ivalo in Finland have reported repeated signal losses, which have been traced back to Russian electronic warfare systems across the border. These disruptions test NATO’s resilience and remind local populations that Russia can interfere with civilian life at will.

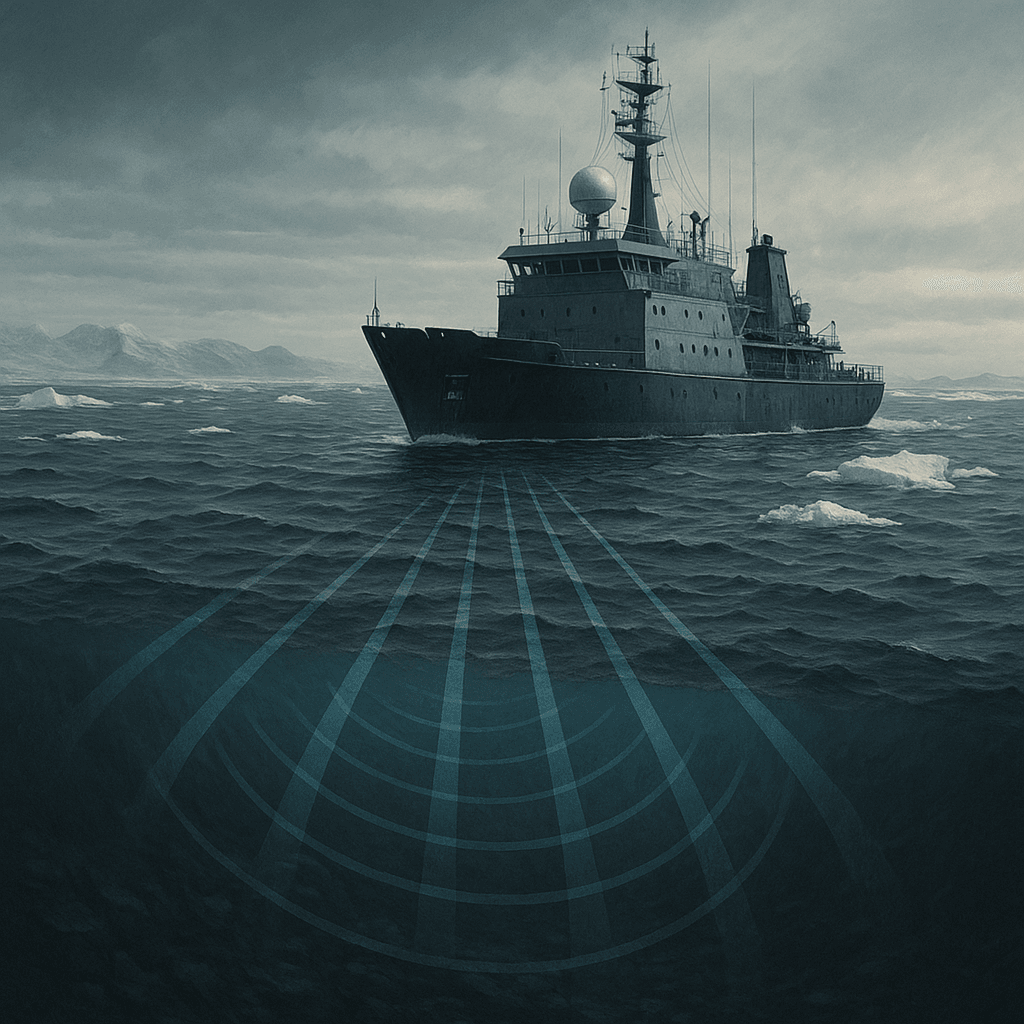

Research Vessels and Seabed Mapping

Maritime activity tells a similar story. Russian “research” vessels frequently appear along undersea cable and pipeline routes. Many carry unmanned submersibles and sonar equipment. Their purpose is not purely scientific. The 2022 severing of one of the two Svalbard undersea cables exposed how easily critical infrastructure can be targeted. Norway stopped short of assigning blame, but the incident fit Russia’s pattern of operating in the grey zone.

Cyber Intrusions Against Critical Infrastructure

Cyber operations add another layer of pressure. Energy companies in Norway and satellite providers in Svalbard have faced intrusions linked to Russian state-backed groups. These attacks are rarely catastrophic. Instead, they probe defenses, gather intelligence, and foster doubt about the reliability of Arctic infrastructure.

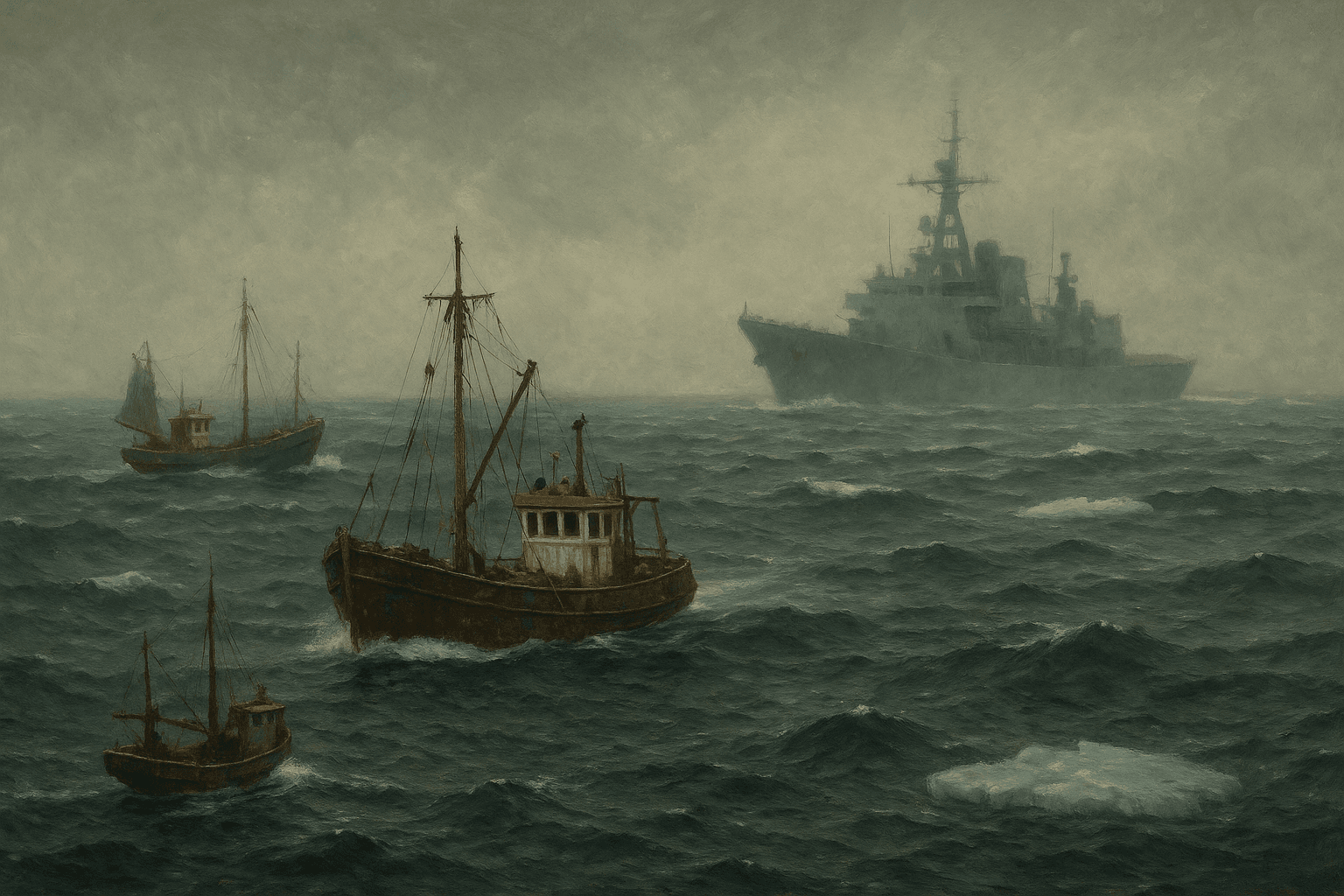

Dual-Use Civilian Fleets

Even Russia’s civilian fleets are drawn into this strategy. Fishing trawlers and commercial ships are often tasked with surveillance roles, blurring the lines between commerce and state power. This dual-use model ensures Moscow maintains a constant presence under the cover of normal activity.

Persistent Hybrid Pressure

Together, these measures represent a campaign of persistent hybrid pressure. By combining electronic warfare, covert mapping, cyber intrusions, and dual-use fleets, Russia maintains the Arctic’s instability. NATO is forced to second-guess every move, while Moscow enjoys freedom of action below the threshold of open conflict.

China’s Expanding Role as a “Near-Arctic State”

Framing the Arctic as a Global Commons

China has no Arctic coastline, but it has declared itself a “near-Arctic state.” Through official white papers and international forums, Beijing frames the Arctic as a global commons. This language positions China as a stakeholder in shipping routes and resources, even though geography says otherwise. The narrative challenges the sovereignty of Arctic nations by suggesting that no single group should control the region’s future.

The Polar Silk Road Strategy

Beijing advances its interests under the banner of the Polar Silk Road, an extension of its Belt and Road Initiative. Chinese companies invest in ports, LNG projects, and shipping along the Northern Sea Route. These moves create economic ties that also serve strategic purposes. Every port facility or shipping venture doubles as a potential logistics node for state activity.

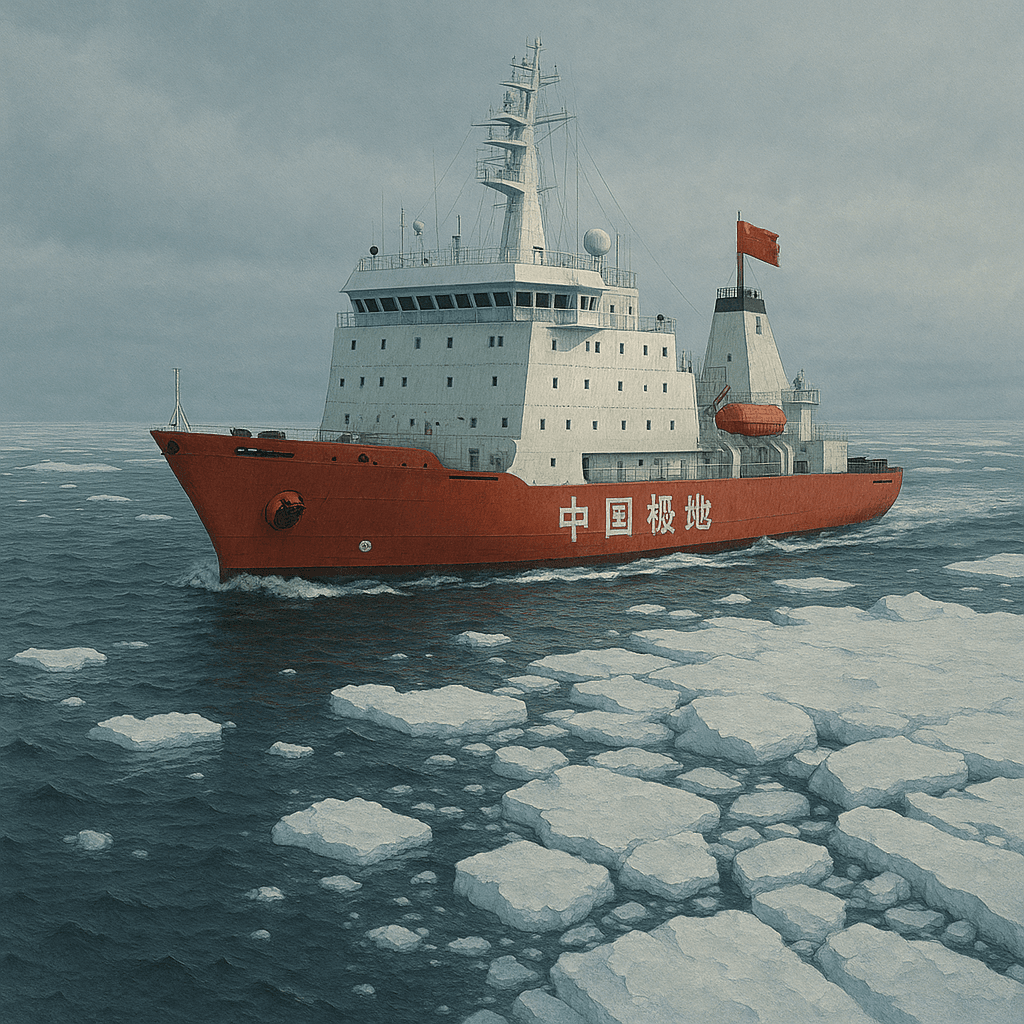

Dual-Use Science and Intelligence

China relies heavily on scientific expeditions and Arctic research stations. Officially, these focus on climate monitoring and environmental studies. In practice, many have dual-use roles. Scientific data on ice conditions, seabed topography, and satellite coverage support both civilian navigation and military planning. Western analysts warn that research stations also provide cover for intelligence collection.

Expanding Maritime Presence

China’s shipping firms increasingly send vessels through Arctic waters during the summer thaw. These voyages are more than commercial tests. They signal intent and normalize Chinese presence in the region. By sailing under the flag of trade, Beijing builds experience and familiarity with Arctic conditions that military planners can later exploit.

Hybrid Pressure Without Bases

Unlike Russia, China lacks military bases in the Arctic. Instead, it leverages economic projects, scientific activity, and information campaigns. This softer approach still carries weight. By shaping global narratives and building commercial influence, Beijing gains footholds that can be converted into strategic leverage.

Strategic Targets: Svalbard, Greenland, and the Polar Express

Svalbard as a Critical Node

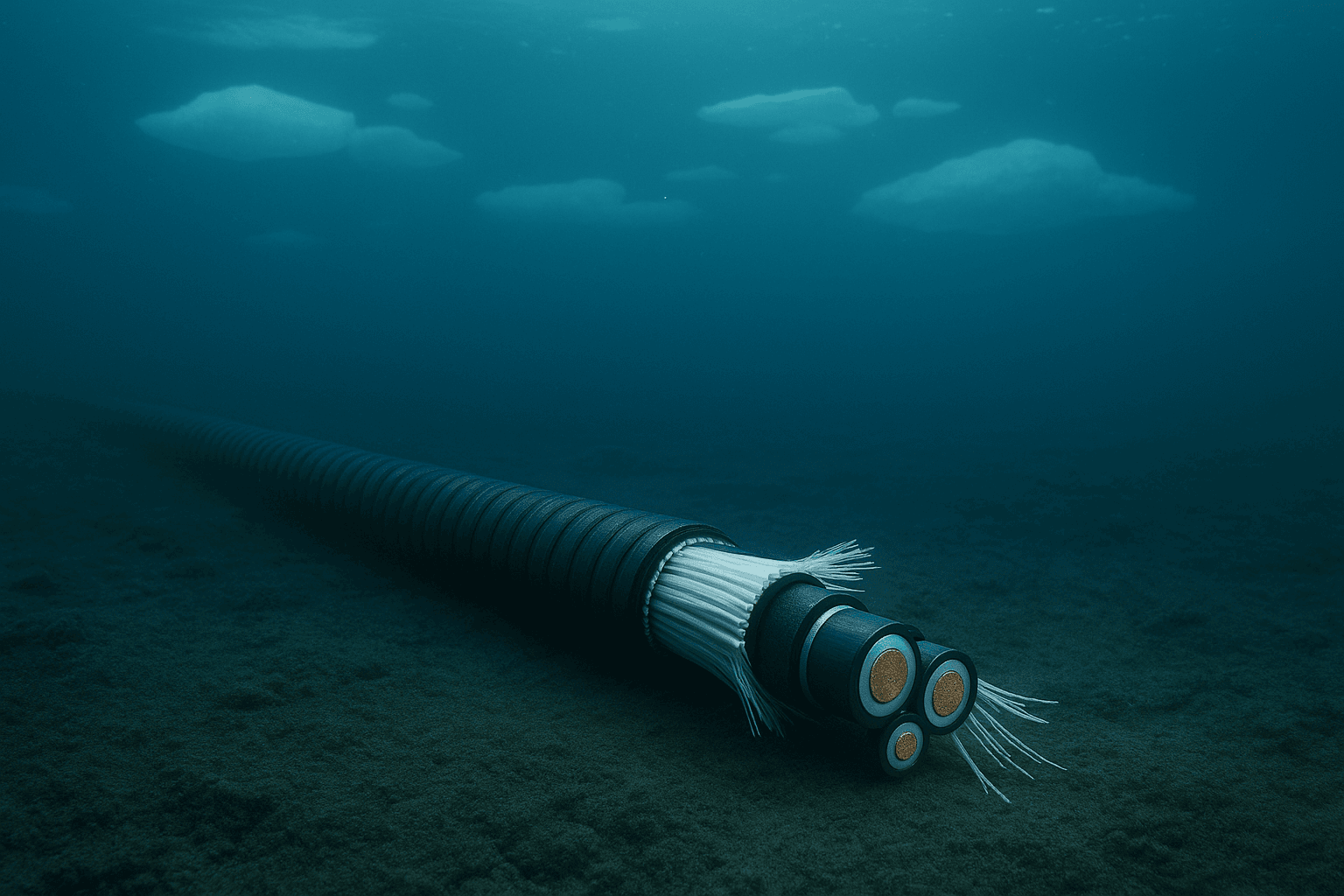

The most vulnerable Arctic asset today is the Svalbard Undersea Cable System. Two fiber-optic lines connect the Norwegian archipelago to the mainland. These links support the Longyearbyen satellite ground station, which relays data from polar-orbiting satellites used worldwide. In January 2022, one of the two cables was mysteriously severed. Norway avoided naming a culprit, but the event highlighted how easily Arctic infrastructure can be targeted. With one line down, Svalbard depended on a single connection — a stark reminder of how fragile redundancy can be.

Greenland’s Lifelines

Greenland is also bound to the outside world through fiber optics. The Greenland Connect and Greenland Connect North systems link the island to Iceland and Canada. These cables provide communications for local populations, but they also underpin NATO and U.S. operations at Thule Air Base and other sites. Their location in remote waters makes them difficult to secure. A single disruption could isolate Greenland from both civilian and military partners.

Near-Arctic Precedents

Incidents in the near-Arctic show the pattern already at work. The Balticconnector pipeline between Finland and Estonia was damaged in 2022, alongside unexplained cuts to undersea cables in the Baltic Sea. No actor claimed responsibility, but the events fit the profile of hybrid sabotage: deniable, disruptive, and calibrated to stay below the threshold of open war. These cases provide a template for what could unfold farther north.

Russia’s Polar Express Project

Looking forward, Russia is laying the Polar Express cable, a planned 12,650-kilometer system along the Northern Sea Route from Murmansk to Vladivostok. Moscow promotes the project as a secure domestic backbone. Yet its length and exposure create a paradox. The Polar Express enhances Russian control but also introduces a new target for sabotage. In conflict, adversaries would see this infrastructure as both a symbol and a vulnerability.

Infrastructure at the Edge of Security

The Arctic does not host dense networks of cables or pipelines under the central ice. Instead, its infrastructure is concentrated in chokepoints: Svalbard, Greenland, northern Norway, and the Russian Arctic coast. These sites combine strategic value with inherent fragility. They are where sabotage and hybrid operations are most likely to strike, not in the drifting pack ice, but along the fragile edges where technology meets geography.

Irish Trawlers and Arctic Civil Resistance

The Irish Fishing Boat Incident

In February 2022, a group of Irish fishermen challenged Russian naval exercises scheduled in Ireland’s Exclusive Economic Zone. The fishermen declared they would continue working in the area, risking confrontation with warships. Their protest was simple but effective. By invoking their legal right to fish and the safety of their livelihoods, they forced Russia to relocate the drills. This was not a military victory, but it was a striking example of civil resistance shaping great-power behavior at sea.

Lessons for the Arctic

The Irish case shows that irregular actors do not need missiles or submarines to influence outcomes. Civil society can exploit legitimacy, visibility, and persistence. In the Arctic, the same dynamic could unfold. Norwegian or Greenlandic fishing fleets could act as eyes and ears along contested routes. Their presence complicates deniable Russian or Chinese maritime activity because any incident with civilian vessels carries political consequences.

Indigenous Communities as Frontline Actors

Arctic indigenous communities, from the Sámi in Scandinavia to Inuit populations in Greenland and Canada, also sit on the front line of irregular competition. Their territories overlap with military installations, shipping corridors, and resource extraction sites. These communities can serve as early-warning networks by reporting suspicious activity, but they are also potential targets of disinformation campaigns designed to erode trust in NATO states. Civil resistance here is both cultural and strategic.

Civilian Shipping as Strategic Pressure

Commercial shipping firms also play a role. Container and energy carriers navigating Arctic waters can be both tools and pawns in a hybrid conflict. Their decisions to sail or not sail affect the credibility of shipping routes such as the Northern Sea Route. Just as Irish trawlers used fishing rights as leverage, shipping firms in the Arctic could unintentionally become part of irregular pressure by refusing risky passages or exposing hostile interference.

Civil Resistance in Hybrid Warfare

Civilian actors bring unpredictability into the Arctic balance. They lack warships and aircraft, but they possess moral authority, legal leverage, and visibility. As the Irish fishing boats proved, even small groups can alter the decisions of great powers. In the High North, these irregular elements could become essential to how resistance and resilience are expressed in the maritime domain.

NATO and the Hybrid Defense of the Arctic

Lawfare as a Strategic Tool

Western states cannot match Russia’s sheer volume of Arctic military assets, but they leverage lawfare, the strategic use of legal frameworks. The Svalbard Treaty of 1920 allows Norway to administer the islands while granting economic access to other signatories. This arrangement has been used to limit Russian activity and assert NATO oversight. Similarly, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) provides a basis for contesting excessive Russian claims on continental shelves. Legal instruments give NATO allies tools to constrain adversaries without firing a shot.

Information Operations and Narrative Control

The information domain is just as important. NATO members consistently frame Russia’s militarization of the Arctic as destabilizing and risky. They also push back against China’s narrative of the Arctic as a global commons. By shaping how the region is perceived, Western governments aim to build consensus among allies and partners. These information operations are not propaganda in the Cold War sense, but strategic messaging that undercuts adversary legitimacy.

Dual-Use Presence and Civil-Military Integration

Western states also rely on dual-use assets. Coast guard patrols, research ships, and scientific stations perform civilian functions but also contribute to maritime domain awareness. For example, Norwegian research expeditions in the Barents Sea double as surveillance platforms. This blending of roles strengthens resilience while maintaining a visible presence in contested waters.

Total Defense Concepts in the Nordic States

The most significant Western innovation is the adoption of Total Defense models. Norway and Finland integrate civilian preparedness into national security planning. This includes training populations to respond to disinformation, stockpiling essential supplies, and ensuring rapid mobilization of reserves. Lithuania, though outside the Arctic, offers another example with its public resilience handbook, which has influenced Nordic practice. These models ensure that if hybrid operations target critical infrastructure or local communities, societies are not caught off guard.

Hybrid Defense as Deterrence

NATO’s approach in the Arctic combines law, information, dual-use presence, and civilian resilience. This hybrid defense posture does not mirror Russia’s aggressive tactics, but it achieves a different effect. It complicates adversary calculations by showing that the High North is defended not only by submarines and fighter jets, but also by legal authority, social cohesion, and civil participation.

What Arctic Hybrid Conflict Could Look Like

Svalbard as a Flashpoint

The Svalbard archipelago remains one of the most likely flashpoints. Norway administers the islands under the 1920 treaty, but Russia maintains economic rights through coal mining and other ventures. In a crisis, Moscow could stage deniable “civilian” disruptions, such as blocking port access or contesting mining sites, while backing them with electronic warfare. Norway would face the challenge of responding firmly without escalating to open conflict.

Greenland and the Battle for Connectivity

Greenland’s importance lies not only in its resources but in its role as a connectivity hub. The Greenland Connect fiber-optic systems link the island to Iceland and Canada, anchoring both civilian and military communications. In a grey-zone confrontation, a cable cut or sabotage event could sever NATO’s link to U.S. and Danish installations. Attribution would be murky, but the disruption would immediately affect alliance cohesion and confidence.

Shipping Routes Under Pressure

The Northern Sea Route along Russia’s coast and the Northwest Passage across Canada are commercial prizes. In a crisis, hybrid actors could target shipping with GPS spoofing, cyber intrusions on navigation systems, or staged “accidents” involving trawlers or tankers. Even without physical destruction, the perception of risk could deter insurers and shippers, undermining economic viability.

Indigenous and Civilian Populations at Risk

Hybrid tactics would not stop at infrastructure. Indigenous communities in Norway, Finland, Canada, and Greenland could face targeted disinformation campaigns. Messaging might claim that NATO military activity threatens traditional livelihoods or that foreign powers seek to exploit natural resources. Such efforts would aim to weaken trust between local populations and national governments.

A Contest of Ambiguity

The defining feature of grey-zone Arctic conflict would be ambiguity. Russia or China could use dual-use assets, research ships, fishing trawlers, or survey expeditions to mask aggressive actions. NATO would struggle to prove intent without escalation. The contest would be less about winning battles and more about shaping perceptions, controlling narratives, and eroding resilience.

The Arctic as a Laboratory for Irregular Warfare

From Frozen Frontier to Contested Arena

The Arctic is no longer a frozen buffer that isolates states from each other. Melting ice has opened routes, unlocked resources, and turned the High North into a contested arena. The region now draws in not only Russia and NATO, but also China, which frames itself as a “near-Arctic state.”

Hybrid Tactics Already at Work

Hybrid operations are not theoretical. They are already happening. GPS jamming in northern Norway and Finland, cyber intrusions against Arctic energy and satellite systems, and the unexplained cutting of undersea cables all point to a shift. The Arctic is being shaped through ambiguity, deniability, and irregular pressure long before open conflict occurs.

Civil Resistance as a Force Multiplier

Civil society actors, from Irish fishermen challenging Russian naval drills to Arctic indigenous communities monitoring local activity, demonstrate how resistance can influence great-power decisions. These irregular contributions complicate state strategies and provide early warning against hybrid activity. They also highlight the importance of resilience at the community level.

Western Responses Through Hybrid Defense

NATO and its Arctic allies have adapted by combining lawfare, information operations, dual-use assets, and Total Defense models. These measures expand deterrence beyond military might. They make clear that the Arctic is defended not just by submarines and aircraft, but by legal authority, social cohesion, and civilian preparedness.

A Test Case for the Future of Warfare

The High North serves as a laboratory for irregular conflict. The region’s geography magnifies vulnerabilities: every undersea cable, port facility, and satellite station is a chokepoint. Its sparse population means small-scale disruptions can have outsized effects. And its political environment, where sovereignty claims meet global commons rhetoric, creates fertile ground for grey-zone competition.

Final Assessment

Irregular warfare in the Arctic is not an abstract forecast. It is already shaping the balance of power. From Murmansk to Svalbard, from Greenland to the Northern Sea Route, the tools of sabotage, disinformation, and hybrid pressure are active today. For Arctic nations and NATO, success will depend on recognizing that resilience is as vital as deterrence. The future of the Arctic will be decided not only by fleets and icebreakers, but also by the strength of societies to withstand irregular threats.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply