Sabotage has long been a hallmark of resistance movements—an action that disrupts the powerful without demanding open battle. From damaged railway lines during the American Civil War to fuel pipeline shutdowns in the 21st century, targeted disruption remains one of the most accessible and effective forms of irregular resistance. Though tools have changed, the core idea endures: striking quietly at the vulnerable seams of an adversary’s system can yield results far beyond the scale of the act itself.

Distinguishing Features

What distinguishes sabotage from other forms of resistance is its strategic subtlety. Rather than seek public spectacle or mass mobilization, sabotage thrives in secrecy. It offers an asymmetric advantage to those with limited means, allowing small cells—or even lone actors—to damage critical systems, impose costs, and erode an opponent’s sense of control. Whether it’s a severed rail line, a contaminated fuel supply, or a ransomware attack, sabotage operates in the shadows, leveraging knowledge, timing, and precision to make its impact felt.

Historical Context

Across history, sabotage has taken many forms—mechanical, psychological, cyber—but its goals remain remarkably consistent: to degrade the enemy’s capacity, to sow doubt and disruption, and to buy time or space for a larger movement to grow. It has succeeded in undermining occupations, crippling logistics, and altering the course of wars. Yet, it has also failed when misapplied, exposing operatives, alienating civilians, or backfiring due to poor planning. These contrasting outcomes reveal sabotage not as a guaranteed solution, but as a tool whose value depends entirely on how, when, and where it is used.

This article explores sabotage as both a historical phenomenon and a modern tactic. It begins by defining its core characteristics and operational logic and then examines its various forms—physical, cyber, psychological, and hybrid. Through detailed case studies, we will analyze what makes sabotage succeed or fail, drawing from both classic resistance campaigns and contemporary operations. Finally, we turn to the insights of influential theorists and practitioners, offering a grounded understanding of how sabotage fits within the broader landscape of irregular warfare today.

Defining Sabotage in Resistance Movements

Sabotage, in its simplest form, is the intentional disruption, destruction, or degradation of a system to produce strategic or tactical effects. Unlike acts of protest or direct combat, sabotage is characterized by its covert nature and its focus on weakening an adversary without necessarily confronting them. Within resistance movements, it functions as a force multiplier—allowing small groups to challenge state or occupying powers by targeting infrastructure, logistics, communications, or morale. It is not just a method of attack, but a statement of defiance delivered through calculated interference.

Purpose of Sabotage

The goals of sabotage generally fall into three overlapping categories: degradation, disruption, and deterrence. First, it seeks to degrade the adversary’s operational capacity by damaging or disabling critical assets, such as transportation networks, energy systems, or supply lines. Second, it disrupts normal functioning, creating confusion, delays, and uncertainty that ripple through military or political hierarchies. Finally, it serves as a deterrent by demonstrating the vulnerability of even well-defended systems, compelling the adversary to divert resources toward protection, repair, or internal policing. In each case, the saboteur aims to create disproportionate effects with minimal force.

Focused Execution

Sabotage is often confused with other forms of resistance, but distinctions matter. Unlike terrorism, which typically aims to instill fear through indiscriminate violence, sabotage focuses on systems rather than people. Its targets are functional, not symbolic: a train rail instead of a marketplace, a server room instead of a crowded square. Likewise, it differs from subversion, which erodes institutions from within through propaganda or infiltration. Sabotage, by contrast, leaves a scar—it is direct action, physical or digital, that disrupts operations without necessarily dismantling the structures behind them.

Strategic Application

Within the context of irregular warfare, sabotage is not merely a tactic of destruction—it is a tactic of strategy. It allows resistance movements to operate asymmetrically, choosing the time, place, and method of attack while forcing the opponent into a reactive posture. The power of sabotage lies not in overwhelming force, but in targeted disruption. It is a scalpel, not a hammer. When aligned with broader political or military goals, sabotage can shift momentum, delay campaigns, and erode the perceived legitimacy or competence of occupying or authoritarian regimes.

Types of Sabotage

Sabotage manifests in multiple forms, each adapted to the tools, terrain, and technologies of its time. These forms fall into four broad categories: physical, cyber, psychological, and hybrid. While all aim to disrupt, each leverages different means and impacts. Physical sabotage might involve explosives, mechanical tampering, or arson. Cyber sabotage targets networks and digital infrastructure, often invisibly. Psychological sabotage exploits perception—planting false information, undermining trust, or triggering paranoia. Hybrid sabotage blends these elements, coordinating attacks across physical and digital domains for compounded effect.

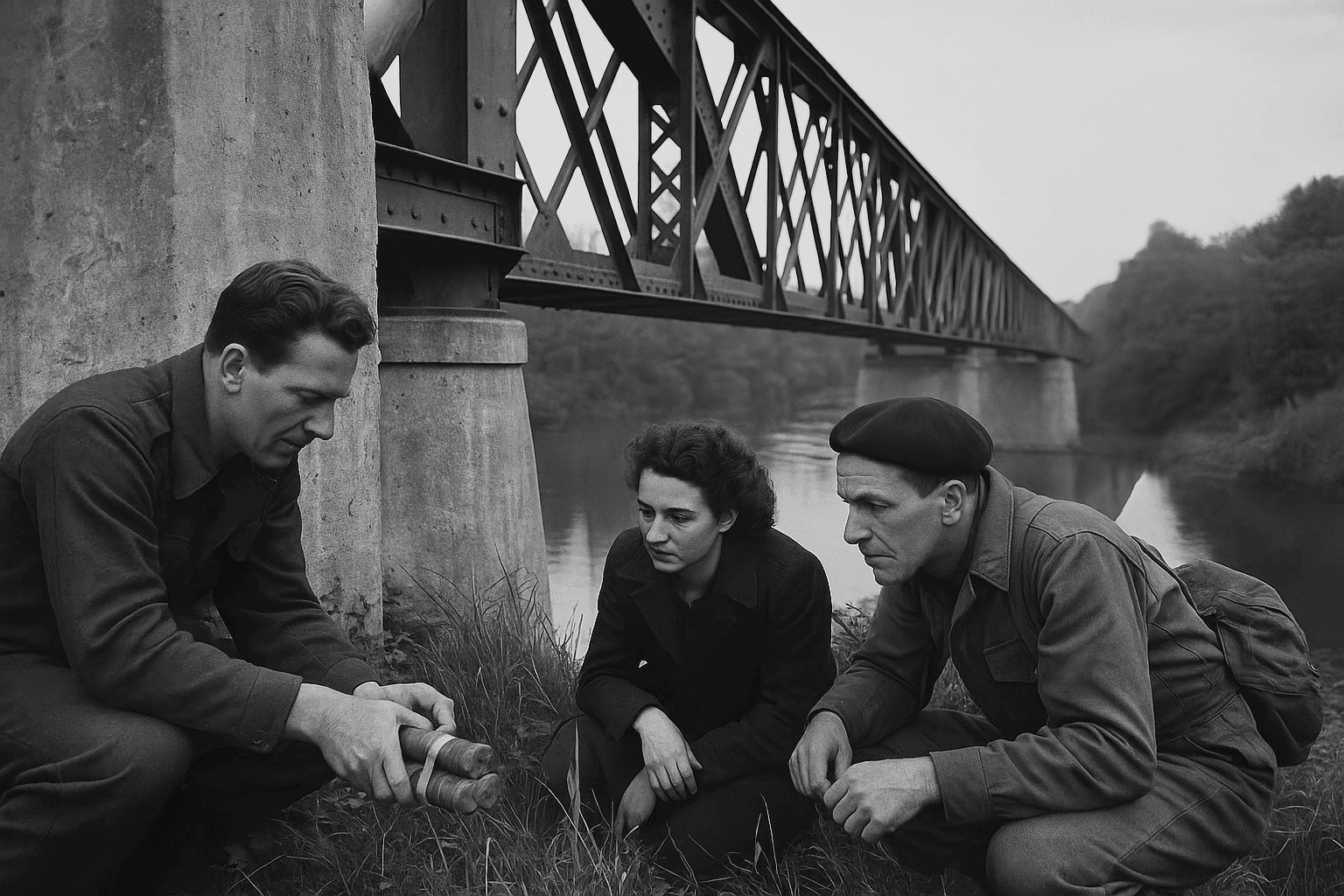

Physical

Physical sabotage is the oldest and most recognizable form. It involves the direct manipulation or destruction of tangible infrastructure—rail lines, bridges, power stations, fuel depots, or machinery. In the American Civil War, Confederate raiders tore up Union tracks and burned supply depots to disrupt logistics. During World War II, resistance groups across Europe conducted rail ambushes, set demolition charges on roads, and used improvised tools to disable vehicles. The key to effective physical sabotage is not brute force, but precision—choosing targets whose loss causes cascading operational effects.

Cyber

Cyber sabotage is a modern evolution, weaponizing code instead of explosives. It targets the digital arteries of modern life—power grids, financial systems, communications networks, and industrial control systems. In 2021, the Colonial Pipeline attack by a criminal ransomware group shut down fuel distribution across the U.S. East Coast, revealing just how vulnerable critical infrastructure has become to remote disruption. Although not carried out by a resistance movement, the incident exemplifies the strategic impact that cyber sabotage can achieve: widespread disruption, panic buying, and costly shutdowns—all without a single physical intrusion.

Psychological

Psychological sabotage operates in the realm of perception. Its goal is not to destroy a machine or sever a line, but to destabilize trust, sow confusion, or trigger fear. During World War II, Allied forces used false radio broadcasts and forged documents to mislead German troops, delay responses, and disrupt morale. In more recent times, this form has expanded to include information warfare—planting false news stories, faking communications, or staging incidents to provoke overreactions. By manipulating what the adversary believes, psychological sabotage can paralyze decision-making without ever striking a physical target.

Hybrid

Hybrid sabotage merges physical, cyber, and psychological methods into coordinated operations that magnify disruption. For example, in the early stages of Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine, cyberattacks on government websites coincided with GPS jamming and kinetic strikes on communications towers, delaying Ukrainian response and confusing civilian populations. These operations exploit the interconnectedness of modern systems: a power outage may disable internet access; a hacked alert system may trigger panic; a train derailment may be timed with a disinformation campaign. Hybrid sabotage thrives in complexity, targeting not just infrastructure but the fragile cohesion of modern states.

Elements of Success

Successful sabotage is rarely the result of improvisation. It demands deliberate planning, rooted in intelligence gathering, operational discipline, and an understanding of the target’s role within a larger system. Resistance movements must know not just what to strike, but why that target matters—what chain reactions it might trigger, how long recovery will take, and whether the disruption aligns with broader strategic objectives. Without this level of forethought, even technically successful acts of sabotage may result in wasted effort, unintended consequences, or alienation of civilian support.

Preperation

Planning begins with intelligence—knowing the vulnerabilities of a target and the patterns of behavior surrounding it. Timing is equally crucial: a rail line disabled just before a major troop movement, or a communications tower taken down during a political crisis, can multiply the effects of an otherwise minor action. In the Norwegian heavy water sabotage of 1943, resistance fighters timed their operation to avoid civilian presence and maximize impact on Germany’s nuclear ambitions. The success was not just in the explosion, but in the calculation behind when and how it occurred.

Operational Security

Secrecy is the lifeblood of sabotage. Operations must be executed with minimal exposure, often by small cells with strict need-to-know protocols. Even the most precise plan can unravel if revealed too soon or leaked to the wrong hands. In the case of Operation Gunnerside—the Norwegian heavy water raid—radio silence, coded messages, and compartmentalized planning helped ensure the team reached the target undetected. By contrast, failed missions like Operation Pastorius were undone by early exposure. Protecting information, identities, and movements is not optional—it is foundational to success.

Resourcefullness

Adaptability separates rigid plans from resilient operations. Saboteurs often work in dynamic environments, where guards shift routines, infrastructure is repaired, or weather alters routes. A successful team must adjust quickly without compromising the mission. During ANC sabotage operations in apartheid-era South Africa, operatives frequently changed targets or delayed actions based on unexpected activity, preserving both the mission and their anonymity. Rigid adherence to a plan, on the other hand, can lead to exposure or failure when conditions change. Flexibility ensures that even under pressure, disruption remains possible.

Case Studies in Success and Failure

Sabotage is a high-risk, high-reward tactic. When executed with precision, it can delay weapons programs, destabilize regimes, or fuel global movements. When rushed or misjudged, it can result in exposure, wasted effort, or operational collapse. This section presents a range of case studies—both historical and modern—to explore what distinguishes successful sabotage from failure. Each example offers insight into planning, execution, environment, and consequence, revealing patterns that transcend era and geography. From wartime Norway to modern-day Ukraine, these cases illustrate sabotage as both art and science.

Operation Gunnerside

In February 1943, Norwegian commandos supported by the British Special Operations Executive (SOE) executed a daring mission to sabotage the Vemork heavy water plant, a critical component of Nazi Germany’s nuclear weapons program. The team infiltrated a remote, heavily guarded facility in deep winter, using skis to traverse miles of rugged terrain. They avoided detection, planted explosives with surgical precision, and escaped without civilian casualties or operative losses. The operation delayed Germany’s nuclear research and is widely regarded as one of the most effective acts of sabotage in modern warfare.

The African National Congress

Facing an entrenched apartheid regime, the African National Congress (ANC) adopted sabotage as a central tactic during its early armed struggle. Rather than engage in open conflict, ANC operatives focused on disabling infrastructure that supported the white minority government—railways, electrical substations, and military depots. These attacks were carefully selected to avoid civilian casualties, emphasizing disruption over destruction. Coordinated by Umkhonto we Sizwe, the ANC’s armed wing, the campaign signaled resistance without escalating into mass violence. It won international sympathy, energized internal resistance, and forced the regime to expend resources on internal defense.

The Colonial Pipeline

In May 2021, a ransomware group known as DarkSide targeted the Colonial Pipeline, the largest fuel pipeline in the United States. The attack shut down operations for nearly a week, triggering fuel shortages, panic buying, and economic disruption across the southeastern states. Though the perpetrators were financially motivated criminals—not political actors—the incident revealed the profound vulnerability of modern infrastructure to remote sabotage. A single breach forced a national response, including emergency declarations and a ransom payment. For resistance movements observing from afar, it served as a case study in the asymmetric power of cyber disruption.

The Russo-Ukrainian War

Since the onset of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukrainian resistance networks have carried out a sustained sabotage campaign targeting railways, power substations, and supply lines deep inside occupied territory and across the Russian border. These operations—often attributed to special forces, partisan groups, or allied intelligence—have disrupted troop movements, delayed logistics, and forced Russia to divert resources to rear-area security. In Belarus, railway sabotage by anti-war partisans hindered Russian troop deployments in early 2022. More recently, attacks on transformer stations and fuel depots inside Russia have illustrated how modern sabotage blends local knowledge, irregular forces, and technical precision.

Operation Pastorius

In June 1942, Nazi Germany launched Operation Pastorius, an ambitious sabotage mission aimed at crippling U.S. industrial capacity during World War II. Eight German operatives were landed by submarine on American shores with orders to destroy factories, railroads, and bridges. However, the plan unraveled almost immediately. One saboteur defected and alerted the FBI, leading to the arrest of the entire team before any attacks were carried out. The mission failed due to poor operational security, lack of local support, and overconfidence in the ability to operate undetected in a foreign environment. All participants were either executed or imprisoned.

All Tactics, No Strategy: Baloch Attacks in Pakistan

Baloch separatist groups in southwestern Pakistan have repeatedly targeted infrastructure tied to Chinese-backed development, particularly the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Sabotage operations have included attacks on pipelines, power transmission lines, railways, and fiber-optic networks. While these actions aim to challenge state control and disrupt economic integration, they have often yielded limited strategic gains. The operations lack widespread local support, are frequently neutralized by Pakistani countermeasures, and have failed to generate sustained international attention. Despite targeting high-value projects, the sabotage campaigns remain largely symbolic, highlighting the difficulty of converting disruption into lasting political leverage without broader alignment.

Russian Backed Sabotage in Europe

In recent years, European intelligence agencies have dismantled multiple Russian-backed sabotage networks operating across the continent. In Poland, Germany, and the United Kingdom, operatives were caught scouting military installations, staging arson attacks on logistics hubs, and attempting to disrupt weapons shipments bound for Ukraine. Despite access to funding and technical resources, many operations failed due to poor tradecraft, compromised communications, and vigilant local counterintelligence. Several arrests were made following digital surveillance and insider tips, underscoring the difficulty of sustaining clandestine operations in open societies. These failures offer a modern reminder that sabotage still hinges on secrecy, trust, and context.

Strategic Utility in Modern Conflict

In today’s conflict landscape, sabotage serves as both a tactical weapon and a strategic signal. For state and non-state actors alike, it offers a way to impose costs, test responses, and shape the tempo of war without escalating to full confrontation. Sabotage can precede invasion, as seen in Russia’s hybrid warfare approach; or it can substitute for direct combat, as in the actions of Iranian proxies striking energy infrastructure across the Middle East. In these settings, sabotage becomes a language of strategic ambiguity—disruptive enough to hurt, deniable enough to avoid outright war.

Infrastructure

One of sabotage’s most powerful applications lies in infrastructure warfare. Striking energy grids, transport corridors, or communications nodes can grind an economy to a halt, complicate military deployments, or provoke political instability. In 2022 and 2023, Ukraine’s ability to strike rail lines and substations in occupied regions forced Russia to reroute logistics and fortify rear areas, creating friction across the battlefield. Similarly, attacks on undersea cables, power stations, and ports have become points of vulnerability in Europe and Asia, raising fears that future wars will begin not with missiles, but with coordinated acts of infrastructure sabotage.

Proxy Warfare

Sabotage is also a preferred tool of proxy warfare. State sponsors can enable allied militias or resistance groups to carry out attacks that further strategic aims while preserving plausible deniability. Iran, for example, has supported operations against oil facilities and shipping lanes through groups in Yemen, Iraq, and Lebanon—undermining regional adversaries without formally engaging in conflict. These acts disrupt trade, shift public sentiment, and force military responses that stretch opponents thin. For weaker actors, sabotage becomes a form of strategic leverage, turning minor assets into instruments of geopolitical influence.

Psychological Impact

Beyond physical and cyber targets, sabotage increasingly shapes perception. When a power grid fails or a roadside device hits a military convoy, the public response often outweighs the material damage. Sabotage can create the illusion of omnipresence, forcing adversaries to second-guess their own security and overextend their defenses. This psychological dimension is amplified in democracies, where public opinion can influence policy and war aims. In this way, sabotage becomes more than a tactical nuisance—it is a form of strategic signaling that manipulates attention, trust, and fear.

Seabed Sabotage: A New Frontier

Beneath the surface of the world’s oceans lies a growing network of critical infrastructure—undersea internet cables, offshore gas pipelines, energy interconnectors, and sensor arrays. These systems are vital to global communication, energy transmission, and strategic surveillance. In recent years, they have also become high-value targets for sabotage. Unlike above-ground infrastructure, seabed systems are difficult to monitor, challenging to defend, and often vulnerable to covert manipulation by submarines, unmanned vehicles, or divers. As competition intensifies beneath the waves, sabotage in the deep sea is emerging as a new and shadowy battleground.

Nord Stream

The 2022 Nord Stream pipeline explosions in the Baltic Sea served as a global wake-up call. Though attribution remains disputed, the incident demonstrated both the feasibility and the impact of seabed sabotage. Two major natural gas pipelines were rendered inoperable overnight, disrupting European energy flows and raising tensions among NATO and Russian-aligned states. Unlike traditional sabotage campaigns, the attack left no visible assailants, no captured operatives, and no clear claim of responsibility, making it a textbook case of strategic ambiguity with profound geopolitical consequences.

The Problem of Attribution

What makes seabed sabotage particularly dangerous is the complexity of response. Attribution is difficult; countermeasures are slow; and repair efforts are costly and time-consuming. Seabed attacks can disrupt entire regions without triggering traditional thresholds for war. They can be framed as accidents, blamed on non-state actors, or simply remain unresolved. This ambiguity allows both state and non-state actors to use sabotage as a strategic lever, testing political will and probing red lines while avoiding direct confrontation. It is sabotage by stealth, calibrated for the age of hybrid warfare.

Technology to Support or Counter

As more states invest in deep-sea capabilities—unmanned underwater vehicles, cable-mapping systems, and seabed warfare doctrines—the underwater domain will become increasingly contested. For resistance movements and major powers alike, the seabed offers opportunities to disrupt commerce, communications, and energy flows on a global scale. Protecting these systems will require new international norms, surveillance technologies, and military doctrines. Seabed sabotage is not a future threat—it is already here, and its silent front is expanding with every new cable laid across the ocean floor.

The Future of Sabotage

Sabotage is poised to evolve alongside the systems it seeks to disrupt. As critical infrastructure becomes increasingly digitized and interdependent, the opportunities for disruption multiply. Smart grids, automated logistics, and cloud-based command systems offer speed and efficiency—but also expose new points of failure. A single vulnerability in a sensor network or control system could cascade across sectors, shutting down not just one site but an entire region’s infrastructure. For future resistance movements, understanding these digital seams will be as important as mastering physical demolition.

Emerging Technologies

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are likely to play dual roles in future sabotage operations—as both tools and threats. On one hand, AI can aid saboteurs in selecting targets, modeling system vulnerabilities, or automating intrusion attempts. On the other hand, it will enhance defensive capabilities, enabling faster detection of anomalies and predictive threat modeling. This arms race will push sabotage toward greater technical sophistication. Already, some resistance-aligned hackers are experimenting with scripts that mimic legitimate traffic patterns to avoid detection—foreshadowing a future in which machines battle silently over which systems stay online.

Decentralization

The decentralization of resistance movements—fueled by encrypted communications, peer-to-peer coordination, and anonymized digital currencies—will make sabotage harder to trace and harder to stop. Future saboteurs may never meet in person, may operate across continents, and may crowdsource their tactics from open-source intelligence. This structure mirrors the very networks they aim to disrupt: distributed, redundant, and resilient. As states invest in centralized surveillance and control, sabotage may increasingly rely on the opposite—fluid, leaderless networks that thrive in opacity and adaptability. The battlefield, both physical and digital, will be shaped by this structural contrast.

Conclusion

Sabotage has endured not because of its scale, but because of its strategic economy. Whether carried out by partisans in wartime Europe, insurgents in the global South, or cyber operators in today’s digitized world, its appeal lies in doing more with less—achieving disruption without direct confrontation. It is the tool of the outmatched and the outnumbered, the language of resistance spoken through broken rails, darkened grids, and corrupted code.

Yet sabotage is no guarantee of success. History shows it to be a tactic that rewards preparation and punishes recklessness. When aligned with clear objectives and supported by local knowledge, it can shift the balance of a conflict. When misused, it risks alienating populations or exposing fragile networks. For resistance movements navigating the complexities of modern warfare, the lessons are clear: sabotage remains a powerful tool—but only in the hands of those who understand when, where, and why to use it.

Sources

- Boot, Max. Invisible Armies: An Epic History of Guerrilla Warfare from Ancient Times to the Present. W.W. Norton & Company, 2013.

- Taber, Robert. The War of the Flea: A Study of Guerrilla Warfare Theory and Practice. Lyle Stuart Inc., 1965.

- British National Archives. “Special Operations Executive Training Manuals.” File Series HS 7, 1940–1945.

- U.S. Office of Strategic Services (OSS). Simple Sabotage Field Manual. Strategic Services Field Manual No. 3, 1944.

- Amnesty International. “Balochistan: Human Rights Abuses by Pakistani Security Forces.” Reports, 2008–2020.

- Reuters. “Timeline: Sabotage and Attacks on Infrastructure Tied to CPEC.” Reuters, 2021.

- U.S. Department of Energy. Colonial Pipeline Cyber Incident Overview, 2021.

- NATO Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence. Cyberattacks on Critical Infrastructure: Lessons from Colonial Pipeline and Beyond, 2022.

- Norwegian Resistance Museum. “Operation Gunnerside and the Sabotage of Vemork.” Accessed 2023.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of South Africa. Volume 2: The Role of the ANC and Its Armed Struggle, 1998.

- BBC News. “Nord Stream: Who Sabotaged the Pipelines?” October 2022.

- Ukrainian Centre for Strategic Communications. “Partisan Activity in Occupied Territories.” Briefing Reports, 2022–2024.

- German Federal Ministry of the Interior. “Foreign Intelligence-Backed Sabotage Networks: Threat Assessment.” Internal Summary, March 2025.

- Small Wars Journal. “The Rise of Seabed Warfare.” February 2023.

DISCLAIMER: Links included might be affiliate links. If you purchase a product or service with the links that I provide I may receive a small commission. There is no additional charge to you.

Leave a Reply